|

|

| |

Across the promotion of more permeable and fluid identities in both queer

theory and activism, however, visibility is still fetishized to the extent that it conceals the

social relations new urban gay and queer identities depend on. (Hennessy 115)

Not only do we live in a white heteropatriarchy, we live in a society with a strict gender-sex

binary. "Gender is a social construction of sex" (Colebrook 9). Consequently, your gender

identity is pre-determined by your sex. Sex is biological, i.e. what sexual organs you are born with,

which determine whether you have an M or F on your birth certificate, while "gender is culturally

constructed" (Butler 9). Anything that defies the ideologies of normative gender is queer, and

anything that is queer defies the ideologies of gender or sexuality. In theorizing the idea of masquerade,

Hennessy claims that images of queers in pop-culture fit a stereotype meant to keep real queers in check

(147). According to Hennessy, gay men are shown as flamboyant or in drag, as entertainment (115). Queer

women, whether they are lesbians or bisexuals, also exist as entertainment. When they are depicted as

masculine or butch—stone-cold, man-hating, ball-busting, butch—they are the asexual sidekicks

who lose the woman to the man, in order to be non-threatening to male

masculinity.14 This gender-sex dichotomy

is reinforced when lesbians are used for male pleasure. In recent years, the majority of lesbian images in

media have been feminine,15 but queer women

still are not put into relationships with other women. They are there as conquests, or objects to enable

male fantasy and pleasure, whether it be in porn or mainstream television; in being conquerable, they are

not a threat to male masculinity, they can be flipped. In some cases, a lesbian character is used to

humiliate a male character, i.e. losing the "hot chick" to another

woman.16 But for whatever purpose queer

characters are used in pop-culture, their representation is masquerade; gays and lesbians are thus rendered

non-threatening to the ideologies of a mainstream white, heterosexual, patriarchal society. The L Word

challenges such ideologies by representing lesbians as significant in ourselves, not because of any relation

we might have to masculine identifications and values. But one of the ways The L Word does this is

by representing lesbians as sexual beings enjoying each others' (beautiful) bodies. The question then, is

whether breaking out of the usual mainstream (ideological) stereotyping of lesbians as asexual or as

unattractive butches (in terms of mainstream heterosexual beauty standards) who lose out to men is positive

or negative. In breaking stereotypes are we also displacing those that fit these stereotypes? Are we then

conforming to a male gaze, i.e. targeting a male audience? Or, perhaps it is just a move to market a new

lesbian image based on consumption.

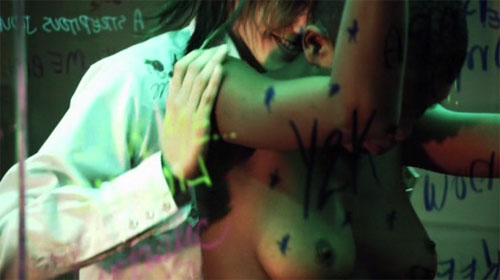

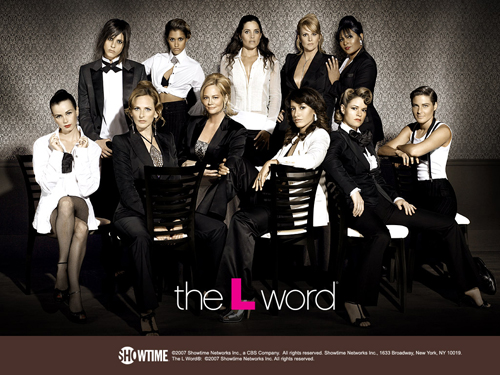

For a show that is supposed to be diverse, the cast is very white and homogenous. Of the 18 main characters over four seasons, only five have been women of color (all the men have been white), and one of these woman could very easily pass as white (an issue which is rarely discussed in the criticism of the show). An even smaller number of the main supporting characters (appearing in more than one or two episodes) have also been white. Women of color are more of a background, like art on the wall. In fact, in episode 311 we see exactly this; a black woman (dark skinned and extremely short hair pictured below) appears at a mostly white party, labeled as performance art, and stands naked in the middle of the room, caged in a plastic box, to be viewed. The woman is put on display and given no real voice; she writes on the wall while others write messages back. She is ogled by the upper-class, white lesbians at the party. Then Shane joins her in the box and starts to kiss and grope her. This image is appalling. She seemed to be more a possession than a real person, especially as Shane penetrates her box and begins to seduce her from behind. The fact that Shane in no way gets to know her (doesn't even ask her name), that she seems to take control of her, objectifies the woman further, thus creating a hierarchy of power. But this is not unusual in that most of the characters of color on The L Word adhere to some sort of stereotype. Carmen and Kit are both in the hip-hop or R&B music business. Kit is also an alcoholic and not as skinny as the other women. Carmen's character is exoticized. Papi and supporting character Candace both work in the service industry (working class jobs). Bette, Kit and Tasha have more hardened (or aggressive) personalities than the white women on the show, a common stereotype of black women, and Bette becomes abusive on several occasions. When a woman of color is added to the show, her stereotypical representation is often more problematic than the lack of diversity.

|

| Woman in the box

writing on walls while people on the outside write messages

such as "Sweet Baby" and "Lick Me." |

|

| Shane joins the

woman in the box. Notice how they are positioned and the way that the woman's face

is covered; it shows the power relationship between the two women. Screenshots from

episode 311, "Lest We Forget," aired on 19 March 2006. |

Class is also uniform amongst the characters, even for those who are supposed to be holding working class jobs.

While Shane and Jenny seem to be

making little or no money in the beginning, they, alongside the rest of the cast, live middle to upper class lifestyles,

in terms of their possessions, tastes and social endeavors. The same is true for Max, who starts off

the show as very working class, thus not fitting in with the stylish L.A. lesbians. This class status is hard to believe,

considering that Max was a computer programmer prior to the trip across country. Those characters who do start off with

more working class jobs, seem to eventually move into a more comfortable economic class status as the show progresses.

Aside from the similarities in class, the cast places very close to each other on the gender continuum, as femme. Max, added in the third season, is male-identified by the end of the season, not butch. The only woman who could truly be considered butch is Tasha and she was recently added to the cast halfway through the last season. Though it is nice to finally see a butch character, she also comes in layers—black, butch and in the military. This is a realistic character, but why make the black character butch? Why place the butch character in the military? Prior to the fourth season, the somewhat androgynous Shane may have been meant to be that token character. Her gender identity is different from the other characters' and is truly a piece of the larger spectrum, but this identity is more fluid than it is butch, as her long hair is sometimes feminine looking and she is seen in both feminine and masculine clothing. Her character, as well as her appearance, became slightly more femme in the episodes following the series' premiere. Nevertheless, regardless of where Shane lies on the gender spectrum, what is most problematic with the show is the general lack of diversity in relation to the characters' gender identity, body image, economic status, social class, and race and this lack of diversity does not change much with the latter seasons.

Season 1 Media Images

(The L Word on Showtime – Get the Newest L Word Downloads and more).

Season 2 Media Images (The L Word on Showtime – Get the Newest L Word Downloads and more).

Season 3 Images (The L Word on Showtime – Get the Newest L Word Downloads and more).

Season 4 Images (The L Word on Showtime – Get the Newest L Word Downloads and more).

However problematic the characters are, the third and fourth season of The L Word have definitely taken a few steps forward with

the addition of two new women of color

(though Papi is meant to replace Carmen), a butch character (Tasha), an older woman and a hearing impaired character (Jodi). This may have been in response to the criticism about the series' lack of diversity. We also are beginning to see a little more fluidity with gender identity, not only with the male characters (Angus),

but with female characters as well. Shane has gradually moved away from femme both in her dress and appearance, though as we see

in the third episode of the third season, she is reluctant to identify as such when new character

Moira implies that they are both butch. With Moira, we see what is believed to be the

emergence of a new, butch character (at least for a moment), but the deeper the show dives into who Moira is,

the more problematic this character becomes (Moira begins to transition towards her inner male, Max). The term "butch" describes a

woman who is considered masculine (generally a self-identification) while a transman, what Moira is becoming, is a

woman who feels that she is a man, and thus transitions into one. "With the new masculine characters (whatever

their biological gender) to come on The L Word, we hope to see a wider representation of the enactment of

alternative masculinities" (Moore 171). Max gives us a wider representation of masculinity, but is not butch. Thus,

these alternate masculinities only touch on gender diversity and do not really deconstruct conventional gender binarity. We could give Chaiken and Showtime an "A" for effort for this new diversity, but we still have a show filled with very feminine, mostly white, able-bodied, upper-class women. In addition, the guest stars on the show are still more products to consume than actual supporting characters.

Season 4 Images (The L Word on Showtime – Get the Newest L Word Downloads and more).

Those who seem to pull away from the homogenous nature of the show's representations definitely seem to do so in layers.

And the few main characters that show any diversity

come with other problems. The show carries unrealistic portrayals of body image with the sole departures from this being

Kit,

the only noticeably non-white woman in the first season (Bette being more ethnically ambiguous, especially prior to issues

of race being discussed) and Phyllis. Kit is both black and has curves

and Phyllis, though white, is an older woman, thus she is allowed to be more voluptuous than the younger characters and therefore does little to challenge mainstream

beauty standards.

Chaiken’s response to this homogenized body image is “[t]here are those viewers who perhaps rightly take

issue with the attractiveness of the cast" (Glock). This lack of recognition of the diversity of beauty standards in the

lesbian community suggests that the show promotes the commercialization of an acceptable mainstream lesbian identity,

while ignoring lesbians who do not conform to this identity. Samuel A. Chambers states that the addition of more diverse women in the show, specifically women of color, would take away from realistic representation of lesbian lives because not many of us belong to a group that is diverse in regards to “sexuality, gender-identification and performance, race and class” (83). Though few of us have a core group of friends where everyone's backgrounds are completely different, it could be argued that most people have friends who are certainly more diverse in their race, sexualities, gender identity, shape and size, and economic background than Chambers is implying.

Will these layers only serve to suggest that (non-white) racial identities and transgressive gender are linked or that

all white butches really identify as men? Will people who do not know butch lesbians now think that all butch women want

to be men (not that this does not already happen)? Will the racially stereotyped characters keep lesbians of color from

coming out? Is it okay to try to debunk stereotypes of lesbians as butch but continue to keep stereotypes of black women

as aggressive and Chicanas and Latinas as exotic? Though it is important to bring out the story of Moira-Max, to include

women of color and to attempt to defy stereotypes of lesbians as butch (while still ignoring the stereotypes of the queer

community as white), in the long run, these issues will only re-enforce the ideology that lesbian visibility has been

creating since Ellen came out—lesbians are just like everyone else. But this statement suggests an unrealistic

lack of diversity in the queer community. We are not like everyone else. Some of us are like the entire cast of

The L Word. Some of us are like Moira. And some of us are like Max. But most of us are not

represented at all.

| |

|