Irigaray's Eastern Turn: The Tantra of An Ethics of Sexual Difference

Simone Roberts

"It is incumbent on the creative imagination of our philosophers, artists and scientists to rediscover not what is most distant, but what is most near and everyday: the mystery that each one of us is. To reinvent love, as the poet seeks to do, we must reinvent the human person."

- Octavio Paz, The Double Flame

[1] That's us. Of course, I realize that Paz's call to reinvent love and being human sounds vacuous when read against the backdrop of extreme postmodern theories of the subject, and thus of the person, as split, overdetermined, schizoid, ironic. Some of these theories, no matter how much they are attempts to account for the over-presence of competing cultures, media, discourses, styles of being a subject or self, ultimately serve quietist and conservative ends. Luce Irigaray and Octavio Paz's writing run along more revolutionary lines of desire, a double flame, a double desire that requires we begin to think of love as an art, as a conscious and mature process between two fully articulated people. Irigaray's An Ethics of Sexual Difference stands as one example of a philosopher trying to reinvent the human person, trying to make love possible. One element of this reinvention is a turn to the East and the ancient philosophies of Tantric Yoga. The advantage of thinking about gender and love under the influence of Tantra is that it, like all yogic practices, takes the relationship of soul to body, gender to gender, lover to lover to be a conscious, disciplined, artistic act. The revolutionary, if not novel, insight that Paz and Irigaray coincidentally share is that love and pleasure are not simply unconscious and hedonistic flights from mutuality and responsibility, but in fact are their most profound expressions.

[2] The split, ironic subject, as we know from Irigaray's critiques of philosophy, is an European masculine subject recently challenged by the discourses of genders, cultures and ethnicities it was accustomed to relegating to animality more or less on the dualist models of the mind-body split. This subject's, this self's, construction makes love between the sexes impossible because, again according to Paz:

Everything is against it: morals, classes, laws, races, and the very lovers themselves. Woman has always been for man the 'other,' his opposite and complement. If one part of our being longs to unite itself with her, another part — equally imperious — rejects and excludes her... By converting her into an object and by subjecting her to deformations which serve his interests, his vanity, his anguish and his very love, man changes her into an instrument... Woman is an idol, a goddess, a mother, a witch, a whore, or a muse, as Simone de Beauvoir has said, but she can never be her own self. Thus our erotic relationships are vitiated at the outset, are poisoned at the root. (197)

The masculine subject-self is torn. The feminine subject-self is covered over with his plethora of projections born in masculine fears and unknown for/to herself. Neither gender has or can overcome these splits because in the axiological models they are absolute in their status and value, and because in the Postmodern models all are reduced to the same rubble by extreme and specious interpretations of insurgent and valuable ideas like différance. Neither the binary nor the différance rubrics, however, can fully rescue intersubjective or interpersonal relations from the poison at the root because neither allow what the Tantric model allows: integration of/and multiplicity.

[3] That integration or mutuality, what in ethics is called reciprocity, places the practice of love and the practice of pleasure at its center. The fear of the "irrational," the "emotional," the "natural," and the "feminine" expressed by patriarchal culture is, I believe, a rationalization of a fear of pleasure and a consequent desire not to mature into a personal, civic, and cultural balance. Patriarchal cultures, (over)generally, figure pleasure as a total loss of ego boundaries, a kind of psychosis. And, that fear is justified. Sexual and spiritual pleasures are part of incredibly powerful energies in the human being that, without the shaping force of discipline and arts of loving, can overwhelm the self-subject. Like the darkest parts of the self, the highest are incredibly powerful, even frightening because they equally can change us forever. We need tools for approaching and embracing both, otherwise we tend to fall apart in their thrall. Fortunately, we have these tools: for the darkness we have psychoanalysis, for the light mysticism.

[4] Irigaray's ethics, under the influence of Tantra, indicate the possibility of a personal, civic, and cultural balance between the sexes and genders that can assuage this long-standing patriarchal neurosis, this ahedonia Paz describes so eloquently, that has resulted in so much psychological, intellectual, sexual, and political suffering for people of both genders. This essay seeks simply to introduce a few basic points of Irigaray's ethics of sexual difference and their basis in Tantra.

[5] Irigaray's theories never leave the breathing human being behind in their discussions of subjectivity. In response to her axiom that the spirit and the body are intimately interwoven, are pathways to and homes for each other, I have created two rather awkward neologisms. In this paper, I signify the other with the combinant term other-subject to highlight both the denial and reality of being or agency in the personal and cultural other. I refer to the subject as subject-self to point up that the linguistic post-structural theories of the subject have often forgotten that "I" is also a person; or, in the case of literary characters and poetic voice, a type of person. My hope is to remind the reader consistently that it is only embodied that we approach each other and the divine within each of us.

[6] In Irigaray's ethics, which necessarily implies kinds of subjectivity and being human, integration and reciprocity lead neither to the old model of the subject as totalized, rational, self-contained, nor to a simple placing of different subjects or aspects of self next to each other in a school lunch room and expecting them to just get along from there. Taking love and fecundity as the basis and goal of ethics, Irigaray's transvaluation of subjectivity and being human is far more subtle and far more demanding than merely trading punches across a sexual battlefield or an ethnic partition.

Diotiman Relation

[7] Irigaray argues for a culture and society in which a fuller, richer, more divine form of love and interaction of selves would be possible, in which women and men would be possible. This love, in its Diotiman and Tantric forms, subtends her entire ethics. In the opening essay of An Ethics of Sexual Difference, "Sorcerer Love: A Reading of Plato, Symposium, 'Diotima's Speech,'" Irigaray describes Diotima's dialectic:

It is love that both leads the way and is the path. A mediator par excellence.

... At the risk of offending the practice of respect for the Gods, she also asserts that Eros is neither beautiful nor good. This leads her interlocutor to suppose immediately that Eros is ugly and bad, as he is incapable of grasping the existence or the in-stance [standing in oneself] of that which stands between, that which makes possible the passage between ignorance and knowledge...

[Between] knowledge and reality, there is an intermediary that allows for the encounter and the transmutation or transvaluation between the two. Diotima's dialectic is in at least four terms: the here, the two poles of the encounter, and the beyond — but a beyond that never abolishes the here. And so on, indefinitely. The mediator is never abolished in an infallible knowledge. Everything is always in movement, in a state of becoming. And the mediator of all this is, among other things, or exemplarily, love. Never fulfilled, always becoming. (21)

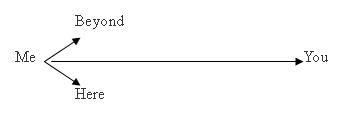

The usual dialectic is one in which there stands a subject, an other, and the subject's relation to the future and present.

Fig. 1.

The other is other in part because she/it has no relation to time acknowledged by the subject. The other is an animal to be domesticated; or, if recognized as an equal, considered a hostile freedom, as Levinas has put it. Mediators are also figured as angels, or daemons in Irigaray's work. Angels are creatures both flesh and spirit, temporal and eternal — they are the prana (breath, life force) of a being, and the pathways of energy and gesture between us, and the pathway of our relation to the divine. Similarly, Eros in Diotima's speech. Love then, is both an angel that might move between persons and is the very path or possibility of that exchange. This angel-path is also very closely linked to the interval and its function as a 'between' for both subjects. In Irigaray's thinking, angels, interval, between, mediation, all these terms remind us that we exist in various modes of interrelation.

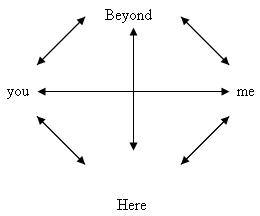

[8] In a dialectic of four terms, that accounts for this complex interrelation, that is one that accounts for the physical, temporal, and eternal dimensions of being; the process can't stop at the advantage of one of the terms — subject or other. There are, in fact, two subjects, each other to each other. A rough diagram of this quadripartite dialectic, specified as intersubjective, might be:

Fig. 2.

Love is the "intermediary between pairs of opposites: poverty/plenty, ignorance/wisdom, ugliness/beauty," men and women, me and you (of the same gender), spirit and flesh. Each of the arrows, as well as the whole field of intention they indicate is love which "leads the way and is the path." When Irigaray calls for new ways of thinking and moving in the world, it is a total cultural shift away from control as power-over she demands of us and for us. This 'dialectic' refuses any one term's rights or being over any other term's rights or being — it operates in what Irigaray calls a chiasmus, or 'double loop', 'double syntax,', 'double desire'. Or, what Paz calls "the double flame."

[9] Irigaray finds the Western definition and practice of love impoverished partly due to the relative non-autonomy of women. Its purpose is reduced to reproduction instead of the fecundation of the two adult partners. This fecund and ethical love not only allows, but insists on the very mutuality and pleasure patriarchal cultures are designed, as Irigaray's feminine deconstructions have shown, as a kind of defense mechanism against the masculinist neurosis concerning both mutuality and pleasure. In Allan Johnson's description of the central characteristic of masculinity under patriarchy, the core value is control which fuels fear (of losing control, or seeming to be out of control), competition and aggression (in order to get control), and has the effect of cutting men off from the possibility of emotional intimacy (out of control) (26-29). But that control cuts men off from women and our ways of experiencing and knowing ourselves, men, the world; and has the added benefit of festering resentments. A dominant person who creates their sense of control and safety with the tools of fear and (potential) violence must live paranoid that the repressed group or person will rebel and undermine their control and authority. With control as a prime value, and with all of its implications for behavior, social structure and relations, people particularly bound up in these values, or in reflecting these values, will have the openness and loss of this brand of control available to them. To imagine out way out of patriarchy, we must recognize this core value and its effect in shaping masculinity and femininity. It leaves the masculine subject-self constantly on the defense and the feminine subject-self constantly chafing against needless restrictions. Irigaray's ethics and practices radically relax these power relations and convert them from a constant cold war to a deeply beneficial partnership on many levels of being. Because Tantra takes the balanced mutuality of the masculine and feminine as its founding assumption (proved again and again by centuries, even millennia of practitioners), it's a perfect model for Irigaray to work with. [1]

[10] Irigaray's description of the role of desire in the Diotiman dialectic of sexual difference could well describe the relations between men and women, as well as the masculine and feminine energies of the chakras in Tantrism, "If there is no double desire the positive and negative poles [of difference] divide themselves between the two sexes instead of establishing a chiasmus or a double loop in which each sex can go toward the other and come back to itself" (Ethics 21). Double desire takes place in an interval filled by and approached with wonder, which Irigaray also calls recognition. In which the other-subject is beheld "always if for the first time," and in such a way that the self never takes "hold of the other as its object" (13). Without double desire, that is the positivity of the desire of both subjects, one member of the dyadic pair is banished to abjection. In Tantrism as in Irigarian ethics, the self and other must be and be respected as fully articulated human beings and must be allowed to remain "subjective, still free" (13). The ethical regard of/for the other-subject, wonder, requires a double responsibility. First, each subject-self is required to regard the other-subject as free, and to foster that freedom and creativity as much as their own. Further, each subject-self is required to approach the other-subject with/in wonder, that is, with the expectation of finding surprise there. Second, and consequently, each subject-self is required to be surprising, to change and become and to manifest these changes, to be wonder-ful. Both subject-selves are required to desire each other out of generosity, not out the lack that is my culture's motive of desire. This wonder and positive desire are what Irigaray calls fecundity. Like love or respect, wonder and becoming mean very little if not externalized in gesture and manifestation. Tantric practice underlies expectation, wonder, becoming, because like other spiritual practices Tantra fosters becoming and thus the ability to surprise. Tantra fosters freedom because each sex has a gender specific to it and complex enough to represent it. Further, in their relations to their gender, men and women are thought of as at once carnal and divine. "The link," Irigaray argues, between "the masculine and the feminine must be horizontal and vertical, terrestrial and heavenly" (17). Tantrism accomplishes this link in that women are these goddesses, men are those gods, as well as their own human selves. The work of contact with the divine is accomplished, actively sought, in much the way that Irigaray argues we must accomplish our genders; and it helps that Tantra was born long before monotheistic religions, and their defenses, and then resurges in Western cultures in the twentieth century when the more adventurous spirits in the West began looking for new ways of being. Tantra was born first in ignorance of Western styles of patriarch, as a response to Hindu patriarch, and then is reborn in response to the Western. It has always been counter-culture. As in this counter-tradition, love and pleasure become meditative practices in Irigaray's ethics, a conscious art founded in and working for respect and reciprocity, not a given fundament on which one might lean, lazily expecting eternal comfort.

[11] Here in the West, we have a symbol for this vertical link, angels. Angels, like Eros, are daemons, or prana, go-betweens who inhabit the space, or interval, between humans and God or transcendence. Ethereal creatures, angels are that which:

unceasingly passes through the envelope(s) or container(s), goes from one side to the other, reworking every deadline, changing every decision, thwarting all repetition. Angels destroy the monstrous, that which hampers the possibility of a new age: they come to herald the arrival of a new birth, and new morning.

They are not unrelated to sex. There is of course, Gabriel, the angel of the annunciation... As if the angel were the representation of a sexuality that has never been incarnated...

A sexual or carnal ethics would require that both angel and body be found together. (Ethics 15-17)

Angels, like love, like wonder and recognition are interval dwellers, like the energy reciprocally exchanged between the sexes in Tantrism; they also are the interval — they let us make love to the divine in each other. "Angles would circulate as mediators of that which has not yet happened, of what is still going to happen, of what is on the horizon," even between individual men and women, between subject-self and other-subject, because in recognition and wonder the poles of the pair are each other's horizons (Ethics 15). This new arrangement of relations would lead into a unwritten future history, something quite other from previous historical arrangements. As the circuit and as circulators, messengers, between men and women and the masculine and feminine in culture, Irigaray's angels are very like the divine energy of tantric ritual; they are a symbol of the spirit or prana exchanged between the sexes-genders in wonder and recognition, in love. They can be embodied in the personal, civic, and cultural gestures between us. The exact shape and content of those gestures and arrangements cannot be predetermined. This is not utopia. We would have to create them cooperatively as we venture on.

[12] The parallels to Tantrism become abundantly clear when she explains the inspiration for her thinking on the subtitle of the book I Love to You, "for a possible felicity in history." In the West, she argues, felicity takes place in the beyond, after death, in heaven:

Such a conception of the world is actually totally foreign to that of other cultures in which the body is spiritualized as body and the earth as earth... I am thinking of certain traditions of yoga that I know something of [Tantra, Vajrayana Buddhism], cultures where the body is cultivated as body, not only just in that muscular-athletic competitive-aggressive way we know only too well and which is not at all beneficial to us. In these traditions, the body is cultivated to become both more spiritual and more carnal at the same time. A range of movement and nutritional practices, attentiveness to breath in respiration, respect for the rhythms of day and night, for the seasons and years of the calendar of the flesh, for the world and for History, the training of the senses for accurate, rewarding and concentrated perception — all these gradually bring the body to rebirth... Each woman and each man acquires immortality [enlightenment] by respecting life and spiritualization... By training the senses in concentration we can integrate multiplicity and remedy the fragmentation associated with singularity and the distraction of desiring all that is perceived, encountered, or produced [as property to control]. (24)

The cultivation of the body as divine, the nutritional disciplines, the view of everything from sex to cooking as a conscious spiritual act, all make the felicity of bliss possible here and now.

[13] Irigaray's description of the role of desire in the Diotiman relation of sexual difference could well describe the relations between men and women, as well as the masculine and feminine energies of the chakras in Tantrism. The first precepts of Tantrism as Irigaray alludes to them cut through Western ideology of the subject like a scream. In Irigaray's words:

The other is not the for-me [think about that for a second, a culture in which men and women co-exist without all the forms of codependence our 'love' now embodies]: an encounter characterized by belonging to a sexed nature to which it is proper to be faithful [that is, a sexed nature complex and rich enough to represent us without divvying us up] ; [characterized] by the need for rights to incarnate this nature with respect; by the need for the recognition of another who will never be mine; by the importance of an absolute silence in order to hear this other; by the quest for new words which will make this alliance possible without reducing the other to an item of property;... by turning the negative, that is, the limit of one gender in relation to the other, into a possibility of love and of creation. (Love 11)

That the other is not for-me has to do with reciprocity. The gestures and prana I should offer to my other-subject, my lover, may very well not be the same as the gestures and prana that I require from my lover. This is what attenuation to difference means. Kate Chopin's "The Story of an Hour" refers to the power relations between the sexes as a powerful will that seeks to bend another human being to our service, reducing them to an item of property. There is no world in which this kind of relation can lead to fulfillment because property has to be controlled. Attenuation to a harmony of sexual difference would mean listening in that absolute silence, as in prayer or meditation. Though not a novel of silence, a novel that represents an attempt to imagine this kind of relationship is Rob Brezsny's The Televisionary Oracle, a story in which two lovers learn how to hear and feel each other's bodies and spirits in what he calls "the drive time," or the interval of meditation. The characters in that story turn the negative, the limit of their gender into a space of mediation and sexuality where admiration and becoming are possible. Irigaray is not alone her thinking. In a less hallucinatory and romping style than Brezsny's, the poetics of Jorie Graham and Carole Maso are also representations of this kind of thinking and relationship. There are many others, but my point for now is only that the posture and practice of a sort of Tantric ethics is already being imagined in the arts.

[14] Irigaray's syntax of "I love to you" might represent this posture. "I love you" means, "I take you as an object of my love, you belong to me by virtue of my loving you [this is every romantic novel that ends in suicide from the secret "LOVE ME, damn you!!!!" buried in it]. But, "I love to you" means that I offer my love to you who are free to benefit from it or to leave it be. "I love to you" respects the interval in which double desire may manifest, the gap between the male and female that makes their mutual fecundation possible. In Tantra and in sexual difference, the interval is not some black abyss of singularity and separation, an obstacle to be eliminated on the way to possessing the other. The interval is that very space that ensures freedom and wonder for both sexes. In sexual difference, "The negative ... means an acceptance of the limits of my gender and recognition of the irreducibility of the other. It cannot be overcome, but it gives a positive access — neither instinctual nor drive-related — to the other (Love 13). This kind of love and ethics is not "unconditional" or infantile and drive related; but like the one Paz describes, it is as wholly voluntary, chosen, generous as it can be — not just possession and control in drag that undermines even the possessor. But this new relation is taboo still, this relation in which subjects would approach each other consciously, with the intent to self-question for the other's sake: to check and see whether I am acting upon you for my own benefit or with you for ours, with a desire welling up from generosity and respect. It is taboo by virtue of a one-sided subjectivity driven by lack and all the nightmares of political, psychological, and sexual terrorism that entails. Fortunately, there are models which can be recuperated and adapted. Those models include the traces we retain of pre-patriarchal cultures, thanks to archeology and comparative religion. They also include the living models of what Irigaray calls, "some kinds of yoga I know," or Tantric practice and the theories of subjectivity and gender which attend them.

[15] Irigaray calls for a posture, both sexual and psychological, in which History would be realized as:

the salvation of humanity comprised of men and women...It is a task for everyone. No one is beyond it, and it makes no one naturally a master or slave, poor or rich... Our principle task is to make the transition from nature to culture as sexed beings, to become women and men while remaining faithful to our gender. This task [the reinvention of human beings]... must not be confused with reproduction... Only women and men concerned to fulfill their gender, both carnally and spiritually, as a couple in society, can engender children with dignity. (Love 29-30)

Desire in a more Tantric formulation is not sublimated into the reproduction of men in their sons, is not "sacrificed to the labor of the community," but is an end in itself, a process of becoming between two lovers (31). (Not a lover and a beloved, a master and slave.) Gender is not a given for each subject, but a possibility to attain to, when aligned with sexed divinities, a task to fulfill, not a label or proscription.

[16] At this level, Tantrism's influence on Irigarian ethics is not difficult to explain. The idea that one's other and oneself should be 'contraries,' mired in a master-slave dialectic is abhorrent to both postures. In its insistence on integrity of self and other and on attraction based not on lack or need but on freedom and becoming, Irigarian ethics echoes the tantric insistence on the complementarity of contraries, or integrated multiplicity. It is a more integral vision: it recognizes the validity and value of many parts, partial views, the contact between which makes meaning.

Tantra

[17] Probably one of the attractions of Tantra for Irigaray is its balance between the masculine and feminine principles as well as between the roles of men and women in practice. A simple example is that Tantra recognizes the different relationships of men and women to earthly-cosmic energy (Sexes 62). Imagine two cones spiraling. The cone that has its point aimed toward the earth corresponds to masculine energy which comes up from the earth in widening spirals. This energy, and the role of the masculine and of men, moves up and outward tending to dissipate itself in worldly production and action. The cone which corresponds to feminine energy and women has its base at the earth and spirals inward tending to concentrate itself in contemplation and gestation in the body before ascending. Of course, individual men and women differ the proportion and expression of these energies given a host of biological and cultural factors. While this sort of oppositional configuration is familiar to the Western mind, its meaning is not. As in Irigarian ethics, these differences are valuable in themselves. As Gavin and Yvonne Frost explain in Tantric Yoga, men and women are both prized for the different energies they bring to rituals, to relationships, and to culture. Each gender and sex has its own relation to its own divine. Neither can achieve 'bliss' or 'ecstasy/enstacy' (the standing outside the self that comes from standing profoundly in the Self of our divinity), however, without the other. Tantra is one of the very few systems of worship in which the feminine presence and spirit is still prevalent and in fecund (or positive and flourishing) relation to the masculine. The goal of Tantra is balance, and without each other, in more traditional Tantras, the feminine and masculine as well as men and women cannot but be out of balance. It's tricky for most Westerners to think and envision this circulation of energy, I know. I have a hard time with it still. But, for the following to make sense, one simply has to grant that such energies indeed move through human beings. Tantra is a practice with its roots in both Hinduism and Buddhism, to which the recognition of and meditation through the conscious "following the breath," or prana is a basic practice. The idea of channeling or manipulating prana also underlies acupuncture, and is essential to understanding Irigaray's conception of humans as spiritual even in their carnality. In Tantra, the most intense prana is kundalani, the sexual energy latent in the body that is released in orgasm, that when harnessed and consciously focused can lead to godhead. Orgasm in Tantra is not dissolution but the most profound concentration of self. The advantage specific to Tantra for Irigaray's ethics that seeks fully articulated representations of both genders is the fantastic complexity of Tantra's understanding of prana as the body's connection to a dual divinity.

[18] The key manifestation of this dual divinity lies in the Tantric conception of the chakras and their divine feminine and masculine aspects. The chakras are energy centers in the body which correspond to major physical, emotional and spiritual aspects of humanity. In Tantra, however, each chakra has a feminine and masculine aspect corresponding to seven incarnations of Shiva and Shakti, the principle god and goddess of Tantra. The following chart gives only a schematic of the chakras and the levels or kinds of prana attending each as well as their differing articulations in the sexes.

Fig. 3.

Chakras and their Correspondence to the Body, to the Psyche, and to Divinity

| Chakra |

Body |

Psyche/Energy of Chakra |

Divinity |

| Base |

base of spine, anus |

FEM: sullen rebellion, envy, raw life force and connection to death, power without discipline, fierceness |

Dakini |

| MASC: isolation in knowledge, contentment, sharing, discipline, satisfaction, patience, mentoring, kindness |

Brahma |

||

| Pelvis |

sex organs |

FEM: ruthlessness, ambition, conquest, urge to mate, battle for opportunity, allure, strength and quickness |

Rakini |

| MASC: loss, endurance for growth, intention, spiritualized masculinity, romance, seeking Vishnu pleasure for others |

Vishnu |

||

| Navel |

digestive organs |

FEM: protectiveness, jealousy, passion, beauty, wealth, refinement, gentility, but still un-self-disciplined |

Lakini |

| MASC: sensuality, laziness, impatience with body and self, inspiration, base desires, secrets |

Rudra |

The navel is the most ambivalent chakra and houses ambivalent energies which can spur one on in one's enlightenment, or cast one back down. For both sexes/genders, this is the pivot. Both Lakini and Rudra appear in disguises, she in fine rainment but holding thunderbolts, he covered in ashes to hide his lower nature. It makes sense, the navel is the center of the body, a balance point between the mind and the sex, the nexus around which the body is balanced physically. But as a representation of energy, the navel and these gods stand in at the mid-point of the ascending and descending journeys of the prana in meditation. We know from reading the great adventure and quest stories that most dangerous point, the point of most likely failure, in the journey is near the middle — that whole agonizing Act III of Hamlet.

| Heart |

heart and lungs |

FEM: balance, self-discipline, knowledge of self, some arrogance, contact with sensual world and need for transcendence, use of sensuality in service of spirit |

Kakini |

| MASC: languor, presentiment, anticipation, alturism, self-confidence, love, parental love |

Isha |

||

| Throat |

throat, speech |

FEM: understanding, mercy, creation becoming, will, risk (this goddess will 'kill' a seeker who balks on the path) |

Shakini |

| MASC: communication, gentleness, mind action, positive and negative aspects of the world, spiritual love |

Shadeshiva |

||

| Brow |

skull, mind |

FEM: completeness, wisdom, intellect cycle of life and death, integration of all feminine aspects in harmony |

Shakti |

| MASC: intellect, separation from spirit through analysis and desolation, knowledge, joy, sharing without squandering self |

Shiva |

Importantly, Shakti and Shiva are the ur-gods of which all the previous gods-energies-aspects of self, and thus the human being, are inflected incarnations. As they are inter-dependent and represent balance of the feminine and the masculine in the self and in the cosmos, so do all the other gods and goddesses. Indeed, in the Hindu and Tantric worlds, the entire cosmos is the child conceived in and sustained by their lovemaking. No aspect of self is rejected. The goal of tantric meditation is not to overcome each aspect, but to incorporate it, balance it, bring it into harmony. The goal is the same between men and women, balance, harmony, not dominance and abjection. Men and women both contain all the feminine and masculine qualities, and all of them must be cultivated as aspects of our genders.

| Crown |

top of head |

FEM & MASC: meditation, cosmic connection, spirit, humility |

Here, the spiritual becomes impersonal, universal, all-encompassing, but still embodied. The paradox of duality is resolved into opening to the divine and transcendence, which paradoxically, can only be reached through our embodiment and duality. Contact with ultimate spirit is considered impossible without the presence of male and female bodies and energies working in tandem. The circulation of energy between persons and their chakras works very much in the shape of a Diotiman relation, with each partner keeping to their own relation to divinity, to time and space, and to self as well as relating to those elements of the other-subject. The blur between them is intended for each to draw on for their own physical, spiritual and creative fecundation.

[19] When energy ascends the chakras, it moves through the feminine elements, only then descending through the masculine in both sexes. In ascent, one understands by fully experiencing and then cultivating, without rejecting any, each chakra's energies and moves toward spirit; in descent, one intentionally illuminates the chakras with spirit. Each chakra also has its own meditation, its own sound, texture, god/dess, totem animal, taste, smell and element (air, earth, fire, water). One purpose of tantric ritual is to become thoroughly familiar with the graced and abjected qualities and aspects of the human being and to find in each a purpose. There is no part of self that is rejected in Tantra, but all parts are disciplined. All people have both the masculine and feminine of each chakra in them, more of one than the other according to their gender and individuality. In some sexual rituals, the partners circulate energy through their chakras and between each other in order to help each other attain balance and enlightenment. The men and women in ritual need each other because, while each sex has both masculine and feminine attributes, each sex is out of balance in energy with respect to the other. Further, while woman may descend the chakras on her own, it is believed that man cannot ascend to enlightenment without her help and guidance; however, descent and illumination is considered easier for a woman with a man's help. Just as she incarnates ascension and learning, he incarnates descent and application of knowledge. Reciprocity and respect, fostering the other-subject in ritual, is total and totally spiritual and carnal. The goal is the carnal and spiritual refinement of both partners through the incorporation and discipline of all aspects of human being. [2]

[20] The mutuality of Tantrism requires of its practitioners recognition as Irigaray defines it: an approach toward the other-subject which includes no attempt to overtake that other, or co-sensuality. The conditions of that recognition: respect and reciprocity, require that men and women both be considered fully articulated, carnal and spiritual beings.

[21] In Tantra, even if we abstract it from its religious practice into an ethical and sexual system, as Irigaray does, love and sex become not by-products of our cultures, but their very center and engine. Sex and love in difference are about the gradual and always incomplete perfection of the self, the soul, the pleasure of the two lovers and the worlds they inhabit. That environment and way of being make sex more than simply the production of children or a release of tension, or conquest, but the creation of children with a deep sense of their own divinity and generosity. Most of the healthiest, most open and generous, relaxedly confident people I know have parents who are actively loving with each other in something like the loving ethics Irigaray describes, and they share that wonder with their children. To achieve this on a cultural and social scale, we will need to (re)invent complex images of the sexes and genders that correspond to their full humanity and divinity. [3] We will have to move out of the critical Postmodern stage to a venture of imagination concerning our ways of life.

Integrating Multiplicity

[22] Tantra is one system which offers its adherents such images. [4] In order for fecundity to blossom, Irigaray argues that men and women, the masculine and the feminine, must be able to recognize and celebrate each other in their difference — and not trap each other in the PhotoShopped pages of Maxim and Cosmo. That is a finiteness in which women will not discover the fierceness and discipline within, and men will not discover the compassionate, playful lovingness within that Tantra teaches us to access, train, and use to the benefit of our flourishing. Irigaray notes that "[to] avoid finiteness, man sought out a unique male God... Man has not allowed himself to be defined by another gender: the female" (Sexes 62). In response to this situation, Irigaray argues that "[divinity] is what we [women] need to become free, autonomous, sovereign" (62). This conclusion is entirely possible without the influence of Tantra, as the example of Octavio Paz and other writers demonstrates, but how much more sense it makes with that influence. Women's multiplicity, like men's, their range of traits and talents all receive divine sanction in Tantra and secular sanction in Irigaray's ethics. Further, we are required not only to value but to sustain the differences between us in balance. The goal is not to replace the feminine aspects of self with the masculine, or vice versa. The goal is to attain balance in difference by integrating and refining all of these qualities. In other words: to attain this balance, we must practice this balance. To eliminate one quality would be to disdain part of one's humanity and part of one's connection to divinity and other people(s). Secondly, such a balance requires the constant maintenance of Diotiman relation. Indeed, in a multicultural world of many traditions and religions, these principles, tantric or ethical, would require adaptation as they came to influence as long as a "felicity in history" remains the goal and test of this venture into cultural renewal.

[23] This felicity requires there being two kinds of subjects, feminine and masculine. No "easy" and really uncomfortable slide into androgyny is proposed here. Androgyny, or women becoming like-men, is absolutely not an ethical option: women and love never appear in that world. Felicity and sexual difference require that there be differences, that they be maintained for their own sake, that they become in relation to each other, but remain determined for themselves. Integration means relation between positively identified and valued terms. Multiplicity means that there be specific terms between which wonder and fecundation may take place. For this to be possible, the sexes as groups and as individuals, need privacy and time to become on their own, as well as togetherness and time to contribute to each other's physical and spiritual becoming. Irigaray is careful to emphasize that in order to become fully articulated (if not enlightened), subject-selves also need periodic isolation away from their partners in order to renew themselves and re-approach each other through the interval as refreshed, slightly changed, wondrous beings. Each of us, in our relationships, in our traditions, in our shared culture and society will have to imagine and invent practices that allow us our full representations and incarnations. Luckily, for all its age, Tantra is a living tradition, and living traditions evolve as they come into contact with other traditions and practices.

[24] On the point of fostering each other's becoming and on difference I would like to take (yet another) quick detour before I conclude. The descriptions I offer in the chakra chart are partial. I want only to indicate that Irigaray has a basis from which to claim that, as Tantrism does, personal fecundity can only be possible when men and women each have some full representation of themselves as genders, when the culture begins to integrate multiplicity. It would seem that so far, America's "multiculturalism" has led us to 'recognize' plural cultures and traditions, but still seems to keep them from communicating. The situation is at no higher a level of evolution for the sexes. Another advantage of ethics under the influence of Tantra is that Tantra as practiced in the US and elsewhere presently is not the province of heterosexual couples only. Like any living spiritual practice, Tantra has been adapted to a number of cultures and to a number of sexual and spiritual needs. While there are Tantrists who believe that practice can only be accomplished between men and women in committed monogamous relations, there are others who believe that Tantra is best practiced in a polygamous situation, and still others who have adapted the meditation and practice for gay and lesbian couples as well: there is no monolith here. Multiplicity is a kind of foundation in Irigaray's ethics. There is no reason that I have yet encountered to think that, brought from the level of theory responding to masculinist culture, Irigaray's ethics would not be as adaptable has Tantra has proven to be. A point on a danger of Tantra as a model is that Irigaray is clearly lifting a philosophy out of a culture that has suffered under imperialism from the very culture she is critical of, and which does not have the greatest track record regarding the treatment of women. There is an interesting double deconstructive move here. On the one hand, Irigaray pressures the Humanist-Imperialist culture with a practice and philosophy which it deplored as superstitious and pagan, but which surpasses the Humanist-Imperialist model in its sensitivity to the at least two-ness of human being. A culture treated as 'feminine' and 'unruly' and 'ignorant' is levered against its masculinist, rational, unified colonizer. At the same time, so much of the Humanist ideal is being held by Irigaray to its professed if not practiced standards that the Indian culture is not let off the hook either. What India has professed in Tantra (which is a marginalized practice there), she also has failed to practice in society. Love as lack is a problem in theory and in cultures at large, and Irigaray is using the heterosexual couple as a lever against that patriarchy-derived dilemma. Furthermore, an examination of her books translated after An Ethics of Sexual Difference indicate that Irigaray has likely become a student of yoga, and possibly of Tantra specifically, and writes as one who has earned her authority. Like Buddhism, Tantra has migrated freely and generously out of its home culture to parts of the world its first practitioners never imagined. These traditions both insist that we each develop a well of spirit and confidence that sustains us as we offer our desire in generosity, not lack, that we not aim our need at each other.

[25] Irigaray argues that a process of "recognition" between selves can overcome love-as-lack and love as othering and help to replace it with a Diotiman relation:

Between us there is always transcendence, not as an abstraction or a construct..., but as the resistance of a concrete and ideational reality: I will never be you, either in body or in thought.

Recognizing you means or implies respecting you as other, accepting that I draw myself to a halt before you as before something insurmountable, a mystery, a freedom that will never be mine, a subjectivity that will never be mine, a mine that will never be mine...

I recognize you supposes that I cannot see right through you. You will never be entirely visible to me, but, thanks to that, I respect you as different from me. What I do not see of you draws me towards you provided you hold onto your own, and provided your energy allows me to hold my own and raise mine with you...

I go towards that which enables me to become while remaining myself. (Love 104)

Our options for understanding and creating our subjectivities, Irigaray implies tacitly, are not limited to choosing between the painful contradictions of Humanism, fundamentalist religiosity, and the flatland of the postmodern 'exploded' subject. We have the alternative of an integrated model, constructed by us with ethical intention in tandem with the contingencies of history. We can recognize that we have a mutually affective relationship with history, as with the planet, and the cosmos, and can take action on our own behalf. We are not simply at the mercy of irony and discourse, we also make them. A subjectivity of integrated multiplicity allows women to develop a divine and thus an ideal of their gender that suits them, that is not subject to the sexisms of Eastern or Western culture, and which would offer women and men a much wider range of expression and modes of being.

[26] No one is let off the hook, however. A range of expression, for men or women, does not imply that damaging behavior or projecting one's or one gender's negative aspects onto the other-subject is ever acceptable. Men cannot make women the bearers of body and animality solely, and women cannot make men the sole representatives of oppression or abuse of position. Men cannot make women their "angles in the house," their Steppford wives; and women cannot make men solely responsible for their well being and protection, their knights in shining armor, their sexual authorities. (And besides, with a goddesses like Dakini and Rakini incorporated into our gender, we wouldn't need to.) An ethics such as Irigaray's, while it offers humans the 'right' to have, hold, and accept their complexity, requires of women a conscious (or more conscious) experience of our own heroism and villainy. Her ethics, and the Tantrism which subtends it, requires in the ideal situation that humans work constantly toward fecundation. As Hugh Kenner once wrote, "Art does not happen." Neither does human becoming. Like any other work or practice, it is joyous sometimes, tedious others. Urgently, this work cannot wait. The on-going work to secure reproductive freedom for women might be a case in point. It is not as if we can 'secure' that freedom and then get on with developing an ethical world of fecundity. Both of these moves need to occur at the same time because, as far as I can tell, women are not recognized as being 'as human' as men or babies, that is not as divine or entitled to their own becoming and self-determination. Both projects are vital, pressing, and further, they are intertwined in a double loop. The integration of multiplicity, the affirmation of the humanity and divinity of the feminine and the female, the recognition and responsibility of men for their own complexity and their existence in a positive relation to women (not to mother-lovers), would both subtend and surpass a world in which women are still rendered as and punished for being sensual.

[27] Irigaray's inspiration from Tantra stands as a model, not a perfect one, not one that can be lifted wholesale, but one that offers a more complex, ambiguous, less binary starting point for determining the course of future culture and life. Its advantage, I think is that Irigaray's ethics and the Tantric system are designed to address the personal and the symbolic simultaneously. What is offered us in Irigaray's ethics a beginning of reinventing the human person and making love possible. Which requires that we change, well, everything.

Renaissance 2.0

[28] Just one point of radical change that readers may well have induced at this point would be the revision of our biases against the body in Western culture. Though we take the meat-house to the gym to exercise it, and we perform various kinds of plastic surgery on it, and wax and make-up and tattoo and shave and bleach and perm and straighten and fill it with pills and protein shakes that will keep the meat-house a shapely and muscular eighteen years old forever — these practices also indicate a need to discipline the body that betrays a still prevalent fear that it might get out of control and run off on hedonistic bender that could destroy us. [5] This fear of the unruly body has been widely exposed as one of the governing drives of Western culture. But in an Irigarian ethics, as in Tantra, the body is the very source and possibility of becoming (if we don't want to go so far as to say enlightenment). Irigaray throws this bias that the body is the site of sin right out the historical window. Her term for the incarnation of spirit that is a human being is the sensible transcendental. We are at once sense and spirit, sensual and divine, sensate and rational. The transcendent, Buddhists and mystics of many traditions have long pointed out to us, resides in the immanent, even the body. Just this insight — given the ways women have been traditionally associated with the body, sex, and sin — destabilizes and begins to reorder the patriarchal order of things.

[29] Our condition as sensible transcendental beings, our being incarnated, affords us one more advantage in terms of ethics — our singularity and mortality, the source of our preciousness and fragility, as well as our boldness and vitality. Irigaray makes much of this advantage, but for the sake of space a journal article, I will turn to the recent work of bell hooks on what she calls a love ethics. Working from various sources in American psychology, hooks has developed an ethics of love that travels paths parallel with Irigaray's, which is no surprise to me: hooks as been an avowed student of Buddhism for decades. Her work helps clearly answer the question: OK, so what do we do right now to make this new way of life?

[30] In All about Love, bell hooks writes of the work required to come to love, and in combination with Irigaray's thought, to an ethics of difference. In the chapter, "Honesty: Be True to Love," she briefly recounts some of the emotional fallout of the second wave of feminism in American culture and personal relationships:

We [women] talked about our desires to be loved for who we really are (i.e. to be accepted in our physical and spiritual beings rather than feeling we had to make ourselves into a fantasy self to become the object of male desire). And we urged men to be true to themselves, to express themselves. Then when men began to share their thoughts and feelings, some women could not cope. they want the old lies and pretenses to be back in place. (48)

The challenge of feminism, of an ethics of love and difference, of what I want to call a culture of pleasure, is to overcome this inertia. The maturation called for by feminism, t step into the venture of an unwritten future history will not be comfortable all the way along. Stepping out of the world's various styles of patriarchy will not be easy, but it just might be better for us than staying in it, where as hooks goes on to say:

The wounded child inside many males is a boy who, when he first spoke his truths, was silenced by paternal sadism, by a patriarchal world that did not want him to claim his true feelings. The wounded child inside many females is a girl who was taught from early childhood on that she must become something other than herself, deny her true feelings, in order to attract and please others. When men and women punish each other [and themselves] for truth telling we reinforce the notion that lies are better. To be loving we willingly hear each other's truth, and, most important, we affirm the value of truth telling. Lies may make people feel better, but they do not help them to know love. (49, ital. mine)

Much less learn to contact the divine in ourselves and respect it in each other! Finding those truths requires, as Irigaray and Tantra suggest to us, time alone, isolated with ourselves and our own relation to the Big Wow (my favorite term for the godhead or the Plentiful Emptiness of the Buddhist satori).

[31] That time alone might not be frittered away in worry over finding the next encounter with our present lover or friends, or in worry over finding our next lover, but in self-love and self-care and self-exploration that can return us to the world and the other-subject refreshed and generous. We each, women and men, can create a space (a room, our whole home if we live alone, my father's work shed in the barn) where we can go to rejuvenate, a place is just as we need it. hooks calls it "soledad hermosa," Spanish for "beautiful solitude," a place where "we intentionally strive to make over our homes [to] places where we are ready to give and receive love, every object we place there enhances our well-being" and reminds of the complex, layered, connected and solitary creatures that we are (65). To be alone does not have to be banishment. Such spaces can also become the retreat in which we consider and revise our relation with our gender, begin to revise the very concepts of our genders, because:

Whenever we interact with others, the love we give and receive is always conditional. [We have, recall, a responsibility to be loving and loveable]... [Largely, this is because] we cannot exercise control over the behavior of someone else and we cannot predict or utterly control our responses to their actions. We can, however, exercise control over our own actions. We can give ourselves the unconditional love that is the grounding for sustained acceptance and affirmation. When we give this precious gift to ourselves, we are able to reach out to other from a place of fulfillment and not from a place of lack. (67)

We are responsible for creating in ourselves a love that is generous, that can enter a Diotiman relation of double desire and of two subject-selves. Without this filling of the well, we fall back to unilateral relations of the Me and you-for-me. Of course, we have overheard this advice before from writers, artists, in Christ's forty days in the desert, in the confessions of the philosophers, and on talk shows, in self-help books, but that does not nullify the fact that it is just so. The dark night of the soul must be incorporated into our waking lives in order to get over it and on the way to our better, and deserved, selves. Dante takes to Hell first, because, as in nearly all tradition, we have to go down to go up. Radical, I know, to suggest so much as this in world where few and fewer learn solitude, and in which the cell phone can eliminate it from our lives if we choose. Even in the self-extending compassion of Buddhism, one must meditate on one's own behalf before one has anything to offer in the way of enlightenment for others.

[32] To rush to a last point from hooks, and to a conclusion for this essay, there is some good news. All of this love is essentially the same, for oneself, to offer others, to create the path that is the goal of a loving ethics that becomes in difference. The love hooks and the ethics Irigaray envision and gather up from their research and thinking has revolutionary strength in it; it sets itself against a masculinist, bureaucratic, militaristic, chauvinist, heterosexist, even fundamentalist context. These biases and bases are incompatible with love and an ethics of difference. The love required is not strategic, not based in need, not possessive. This love that has always languished in the ignored writing of mystics and the work of many psychologists, philosophers, poets and artists is one that we have one more chance not only to overhear, but to heed. This love is, as hooks quotes Erich Fromm, "not just a strong feeling — it is a decision, it is a judgment, it is a promise" to be, I believe, our very best selves on behalf of ourselves, our gender, and our lovers. It consists, quite simply, but in the strongest possible meanings of the words, of: care, kindness, respect, generosity, self-care, curiosity, attention, trust, knowledge, responsibility. We cannot love another without knowing them deeply, in that state that Irigaray calls wonder, and that hooks calls curiosity, attention, respect. Wonder, in French, after all, l'admiration.

[33] The assumption of such postures, that Tantra and yoga call asanas, in a way that grounds us so that we can move toward the other-subject without a rope or a knife in our hands, begins with the personal, but as the work of Irigaray and hooks and others shows, this venture into which we can each step alone brings us eventually together into a kind of cultural continental drift that will change everything — spooky though that is even for those of us want it. Feminism and renaissance have always been for the brave. Be cheerfully brave. Admire. Become admirable. This venture can no longer afford to be a cold war of the sexes. We haven't time for that nonsense anymore. Namaste (the divine in me honors the divine in you).

Works Cited

Frost, Gavin and Yvonne Frost. Tantric Yoga: The Royal Path to Raising Kundalini Power. York Beach, ME: Samuel Weiser, Inc., 1989.

hooks, bell. All about Love. New York, William Morrow, 2000.

Irigaray, Luce. An Ethics of Sexual Difference. Trans. Carolyn Burke ad Gillian C. Gill. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993.

—. I Love to You: Sketch for a Possible Felicity in History. Trans. Alison Martin. New York: Routledge, 1996.

—. Sexes and Genealogies. Trans. Gillian C. Gill. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993.

Johnson, Alan. The Gender Knot: Unraveling Our Patriarchal Legacy. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1997.

Paz, Octavio. The Double Flame: Love and Eroticism. Trans. Helen Lane. San Diego, CA: Harvest, 1993.

Brief Annotated Bibliography:

On Tantra, Buddhism, and Integral Being

Anand, Margot. The Art of Everyday Ecstasy: The Seven Tantric Keys for Bringing Passion, Spirit and Joy into Every Part of Your Life. New York: Broadway Books, 1998. — Anand offers a system of chakra meditations based in Tantra that generate the abiding calm from which love and respect can flow, and does so without ignoring how difficult meditation can be or ignoring the discomforts of the dark night of the soul one inevitably encounters in the ventures of meditation or love.

Daniélou, Alain, trans. The Complete Kama Sutra: The First Unabridged Modern Tanslation of the Classic Indian Text. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press, 1994. — Though the Kama Sutra [fragments on love] is basically a lothario's guide for Brahmanic playboys of Classical India, the Sutras act as a good primer to the delight in the sensual that is basic to Tantra and Irigaray's sensible transcendental.

Douglas, Nik and Penny Slinger. Sexual Secrets: The Alchemy of Ecstasy. Rochester, VT: Destiny Books, 1979. — One of the most popular, if a bit to "hippy-fied" guides to Tantra, this book offers advice on meditation, the symbolism of the god/desses in Tantra, and lots of rather "position centered" illustrations all developed from original sources.

Eisler, Riane. Sacred Pleasure: Sex, Myth, and the Politics of the Body, New Paths to Power and Love. New York, Harper Collins, 1996. — Eisler traces the fear of pleasure as far too liberating a force in Western culture.

Harvey, Andrew. The Return of the Mother. Berkeley, CA: Frog Ltd. Press, 1995. — Harvey examines and seeks to recuperate, with some urgency, the feminine elements of the world's great mystical and religious traditions in a way that makes the divine feminine much less a stranger.

Kinsley, David. Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1988. — The feminine and masculine symbolism of Tantra is based on the stories and symbolism of its Hindu parent-culture. This book illuminates the stories of the major goddesses.

Klein, Anne Carolyn. Meeting the Great Bliss Queen: Buddhists, Feminists, and the Art of Self. Boston, Beacon, 1995. — Addresses some of the intersections and mutual questioning between several schools of feminism and Buddhism by a practitioner of both.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama, and Howard C. Cutler. The Art of Happiness: A Handbook for Living. New York: Riverhead Books, 1998. — A Westerner friendly guide to the practices of compassion for self infused by the Dalai Lama with his own humor and clear understanding of suffering in human being.

Mitchell, Stephen. The Enlightened Heart: An Anthology of Sacred Poetry. New York: Harper Perennial, 1989. — Poems from the worlds wisdom traditions and from literature that crack the self open in all the right ways. New York: Harper Perennial, 1991. — Ditto, but prose, and far more wide ranging in its sources.

—. The Enlightened Mind: An Anthology of Sacred Prose.

Mookerjee, Ajit. Kundalini: The Arousal of the Inner Energy. Rochester, VT: Destiny Books, 1982. — An illustrated guide to the philosophy and practice of Tantra.

Rilke, Rainer Maria. Letters to a Young Poet. Trans. Stephen Mitchell. New York: Radom House, 1984. — Rilke writes to us as solitary and fragile beings. Everyone who needs other people in order to run from themselves should read these letters. Rilke knows both the hard stone and the sunshine of being alone.

Shaw, Miranda. Passionate Enlightenment: Women in Tantric Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994. — An historical recuperation of women in Tantra. It turns out the women were the keepers of Tantric wisdom and the teachers of its practices of divine equality between the sexes. This, it seems, explains its status as a counter-culture vis-à-vis both the dominant Hindu and burgeoning Buddhist traditions of Classical India. Tantra has been and can be a sexist practice as oppressive of women and their divine selves as the rest of patriarchal culture, but Shaw articulates all the reasons that those practices are less ideal than the original foundations of Tantra.

Van Lysebeth, André. Tantra: The Cult of the Feminine. Trans. André Van Lysebeth and Lore Dobler. York Beach, ME: Samuel Weiser, Inc., 1995. — A thorough and dual gender friendly examination of the philosophy and practice of Tantra that emphasizes its non-dogmatic nature.

Wilber, Ken. The Eye of Spirit: An Integral Vision for a World Gone Slightly Mad. Boston: Shambhala, 1998. — Wilber's philosophy is highly complex, interdisciplinary in the extreme, and perfectly accessible to the general reader. In this book, Wilber discusses the present crisis of the world and the future implications of his integral theory in practice, including the importance of feminism and spirituality for that future evolution.

—. Sex, Ecology, Spirituality: The Spirit of Evolution. Boston, Shambhala, 1995. — Wilber's first tome in a trilogy, this book clearly lays out the ground of integral theory for understanding artistic and cultural, personal and psychological, scientific and political, and religious and spiritual as related to each other, as partial but mutually supportive views of the world and truth each with their own methodologies of practice and verification. The shorter version, written for a general audience is titled A Brief History of Everything, which I bought one day because I'd never heard of such a braggish title in my life. But, like we say, here in the South, "It ain't braggin,' if you actually did it."

Notes

[1] Irigaray offers extended discussions of her encounters with and influence from Tantra in several texts I haven't the space to discuss in this essay: Why Different?: A Culture of Two Subjects (Semiotext(e), 2000), To Be Two (Routledge, 2001), Between East and West: From Singularity to Community (Columbia, 2002), The Way of Love (Continuum, 2002). These texts become essential to the articulation of a "poetics of two" I am currently developing, and of which this essay is the preliminary gesture.

[2] This whole summary corresponds to Frost and Frost, 142-263.

[3] A partial bibliography of sources on Tantra follows the essay. I offer it so that readers might venture further along with Irigaray and have these sources in order to continue to make the connections between them, as well as begin to imagine a new future history of our en-carnated and sensual divinity.

[4] For a rich discussion of other such 'models' and ways that men can begin to identify with the fierce and the gentle in the feminine divine, Harvey's The Return of the Mother is an excellent source.

[5] Sandra Lee Bartky's article, "Foucault, Femininity, and the Modernization of Patriarchal Power," from Feminism and Foucault: Reflections on Resistance (Northeastern UP, 1988) elaborates this point brilliantly, and I am in her debt for that.