Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge: Issue 40 (2024)

Phenomenology of Flesh: Fanon’s Critique of Hegelian Recognition and Buck-Morss’ Haiti Thesis

Grant Brown

Villanova University

Abstract: This philosophical investigation interrogates the relationship between G.W.F. Hegel’s concept of the master-slave dialectic in The Phenomenology of Spirit and the critique and reformulation of it by Frantz Fanon in Black Skin, White Masks. As a means of contextualization and expansion of Hegel’s original textual account, I consider Susan Buck-Morss’ seminal defense through grounding the dialectic in Hegel’s possible historical knowledge of the Haitian Revolution. I maintain that despite a compelling picture, Buck-Morss’ insights are unable to fully vindicate Hegel from the rebukes of Fanon, and as a result, Hegel’s phenomenology necessitates a concrete analysis of the actual conscious experiences of the racialized and colonized subject in order to realize its aims. In pursuit of this critical methodology, I develop the upshot and positive movement of Fanon’s critique through what I describe as a “phenomenology of flesh” in conversation with Maurice Merleau Ponty’s The Visible and the Invisible.

“I burst apart. Now the fragments have been put together again by another self” (Fanon 82).

Introduction

Attempts to understand the causality of social conflict and integration have long been the study of any discipline interested in the complex dimensions of human social life. Nowhere does it have more practical saliency than in modern issues of racism, which appear within our contemporary context but from historical fissures that precede us. Influential in attempting to comprehend these complex negotiations of personal and social identity in and between different agents has been the account of recognition exposited in G.W.F. Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit. In the Phenomenology Hegel outlines what he contends is a particularly essential relationship between the master and the slave, which demonstrates that while in physical strength and social position the former rules over the later, on the level of recognition and ability to existentially realize their freedom the dejected wins out, precisely because they are not reliant upon the subjugation of another for their worthiness and value.

While there has been substantial scholarly discussion of Frantz Fanon’s interpretation and criticism of Hegel’s master-dialectic and its ability to achieve an adequate explanation of the colonial situation, there has not yet been a significant treatment of Susan Buck-Morss’ historiographical contributions to these conversations and accompanying potential for vindication of the master-slave dialectic as it appears in the Phenomenology. Therefore, in this paper I will study and compare Hegel’s own exposition of the dialectic, the reconstruction and defense of it from critique by Susan Buck-Morss’ argument that it stems from knowledge of, and is based upon, the Haitian revolution, and Frantz Fanon’s postcolonial, phenomenological, and psychological criticism of the naïve depiction of the slave’s self-consciousness.

I will argue that Fanon’s critique and reformulation of Hegel’s master-slave dialectic stands despite the support provided by Buck-Morss’ interpretation of it as emerging out of Hegel’s engagement with stories of the Haitian revolution. While Buck-Morss is right to understand Hegel’s account as being more supportive and less dejecting of the slave than usually interpreted, Fanon’s phenomenological method and cultural criticism – which I identify through conversation with Maurice Merleau-Ponty as a phenomenology of flesh – demonstrate the lack of saliency of the idealized account of racial recognition when faced with the empirical experiences of the racialized. Such an argument demonstrates both the potential feasibility and difficulty of using recognition as a means for understanding contemporary social conflict, and shows that if it is to be practically useful theories based on recognition must return to the real, concrete, self-conscious experience of those social agents in question.

Hegel’s Master-Slave Dialectic

In the second chapter of the Phenomenology titled “Self-Consciousness,” Hegel begins to expand upon the insights found in the first chapter’s exposition of the characteristics of self-consciousness and the certainty of its use as a foundation for human understanding. He argues that the purely egotistical conception of self-consciousness as in-itself must be exposed to how it unfolds in other things, such as objects and another self-consciousness (§175-177). The need for a new formation of consciousness which can account for these relationships between the self and others leads Hegel to begin the exposition of his theory of recognition which is to ground much of the insights of phenomenology in the 20th century:

Self-consciousness is in and for itself while and as a result of its being in and for itself for an other; i.e., it is only as a recognized being. The concept of its unity in its doubling, of infinity realizing itself in self-consciousness, is that of a multi-sided and multi-meaning intertwining, such that, on the one hand, the moments within this intertwining must be strictly kept apart from each other, and on the other hand, they must also be taken and cognized at the same time as not distinguished, or they must be always taken and cognized in their opposed meanings. This twofold sense of what is distinguished lies in the essence of self-consciousness, which is to be infinitely or immediately the opposite of the determinateness in which it is posited. The elaboration of the concept of this spiritual unity in its doubling presents us with the movement of recognizing. (§178)

In between the beginning and concluding sentences which sketch a technical definition of recognition, to which I will return briefly, is Hegel’s exposition of his concept of unity in difference, frequently characterized as his dialectical process or method. We are to take concepts and ensure they are “kept apart from each other” in order to understand them in what makes them distinct, but at the same time they must be “taken and cognized at the same time” in order to apprehend what is similar or unified between them. In doing so, we gain a better understanding not only of the concepts on their own terms, in what makes them unique, but also in terms of what they may become, how they can emerge as something else. We must have a sort of double vision, as when one views an optical illusion that requires the crossing of the eyes to bring two distinct objects on a page to overlap and create another distinct picture. The truth, so to speak, is the process of synthesis in which a middle emerges out of these two opposites, revealing to us the existence of three distinct but interrelated components. Self-consciousness is therefore understood as operating through a similar synthesis between our status on the one hand as subjects, who have a diverse, multiplicity of rational cognitive activity, and on the other hand our status as objects, who are spatially and temporally bounded, and as we will see, apprehended as such by other subjects. Recognition is therefore an essential component of self-consciousness and defines the movement of synthesis in which one’s identity emerges, as one unified in itself, but diversified in that it has such a status only in so far as it is in another.

Such a view leads Hegel on the path to understanding self-consciousness as shaped by our social and historical location, and after a few more paragraphs he begins to treat recognition as a socially emergent phenomenon, involving the interactions between subjects. In §182-184 Hegel introduces the concept of two self-consciousness recognizing one another, in that they see each other as objects, given their fixed position within their own consciousness, but as the unique type of objects which are also at once subjects, like themselves. In enacting such a series of movements, they both emerge more actualized in their humanity, as they move beyond their mere individual selves and enter the dimension of ethical activity. The treatment of recognition begins therefore in earnest, as our individual self-consciousness strives to assert its independence but is forever thwarted by the appearance and freedom of the other: “Self-consciousness is at first simple being-for-itself, and it is self-equal through the exclusion from itself of all that is other, to itself, its essence and absolute object is the I, and within this immediacy, or within this being of its being-for-itself, it is a singular being” (§186). As a result, such an egotistical movement fails to achieve recognition and certainty for self-consciousness—it is left unsatisfied—as it finds itself dependent on another: “this is not possible without the other being for it in the way it is for the other, without each in itself achieving this pure abstraction of being-for-itself, without each achieving this through its own activity and again through the activity of the other” (§186).

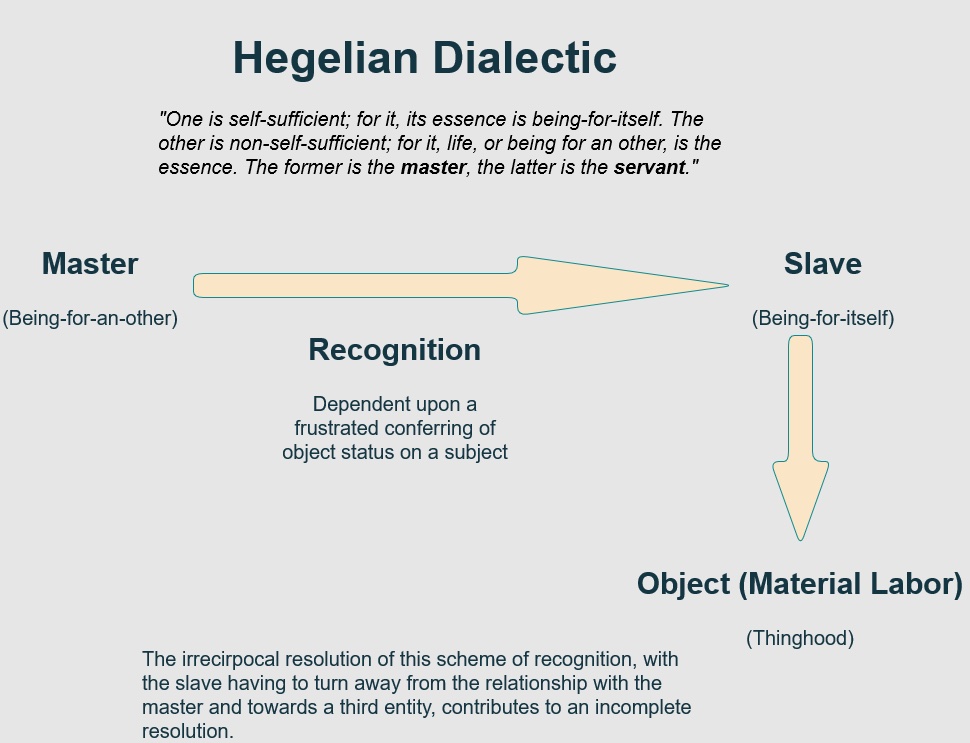

Famously, Hegel proceeds to argue that what emerges is a need to attempt to recede from the egotistical and show that one’s consciousness “is fettered to no determinate existence,” and engage in a deadly struggle for recognition with the other, in which each individual risks their own life and that of the other. In encountering the possibility of death, the objective opposite of our usually subjective experience of living, we achieve a movement in which the subject “ is external to himself” (§187). Finally having escaped the ego, but cast themselves too far astray from the subjectivity of life into the objectivity of death, self-consciousness languishes in the extremes and finds itself once again unable to realize itself (§188). Hegel maintains that this dialectical movement reveals two shapes of consciousness: “It is through that experience that a pure self-consciousness is posited, and a consciousness is posited which is not purely for itself but for an other, which is to say, is posited as an existing consciousness, or consciousness in the shape of thinghood'' (§188). The concepts of master and slave then appear within this conflict as demarcating the self-consciousness which achieves its own freedom from that which is made an object or subject to thinghood: “One is self-sufficient; for it, its essence is being-for-itself. The other is non-self-sufficient; for it, life, or being for an other, is the essence. The former is the master, the latter is the servant” (§189).

In what follows, Hegel traces the master’s position to reveal its insufficiency, as it is in fact they who act like a servant in their reliance upon the latter’s labor and recognition to flourish. The servant is then comparatively better off, but with an imperfect realization of their own freedom as well (§190-196). As Bird-Pollan puts it, “forced labor for the master affords the slave the opportunity to see himself as an agent” (247). However in the case of the master, because he has “not participated in the production of what he consumes, the fulfillment of his desires” remains incomplete, unreal, and imperfect (Bird-Pollan 248). Put differently: “by not having to exert any effort to create the object of his satisfaction, the master also does not reap the benefits of such exertion” (Bird-Pollan 248). In contrast, the slave wins out precisely because “whatever he creates bears the mark of his self-consciousness and his principle” and therefore he comes to realize that “the spontaneity of mind” is freedom and the “true self” (Bird-Pollan 248).

It is already worth taking a moment to consider if the problem of recognition between master and slave in the way it has been proposed by Hegel is a comprehensible or compelling situation. Whether the account has any fidelity to the actual situation of those in the position of domination and subjugation appears acutely important to the demonstration. While in the course of the Phenomenology idealized figures in the dialectical movements may be necessary, it is imperative within Hegel’s own framework to interrogate whether the story told is the most fruitful, and explanatory, pathway for the theory of recognition and its applicability to social conflict. For example, cases of variant degrees of subjugation, as we shall see in Fanon in the context of the racism of slavery, such as the social distinction between different roles on the plantation, or in colonization, with the internalization of different social habits which are alienating to one's self-consciousness, are absent from Hegel’s picture. I would argue that these are within the purview of Hegel’s project but were unable to be realized given his dependence upon the progressive structure and dialectical argument of the Phenomenology. As we will see in Fanon, the structure Hegel gives to the master-slave dialectic serves to “conceal from view how enslaved subjects” are not only materially bound by labor but also psychologically bound such that they “unconsciously internalized their oppression” (Aching 915).

Buck-Morss’ Haiti Thesis

We may expand upon the Phenomenology’s ability to meet these concerns regarding the relationship between master and slave through the insights of Buck-Morss’ “Hegel and Haiti,” in which she argues that it is founded upon Hegel’s personal knowledge of the events and happenings of the Haitian revolution. In Buck-Morss’ account, we can furnish a more charitable picture of Hegel’s dialectic and understand its potential historical foundations and expanded usefulness as a result. She argues that the dialectic should be read in light of his dedicated readership of journals which featured reports on the conflict: “Hegel knew – knew about real slaves revolting successfully against real masters, and he elaborated his dialectic of lordship and bondage deliberately within this contemporary context” (844). She sees this inclusion as truly revolutionary given the context of Hegel’s philosophical contemporaries and influences, who ignored the realities of slavery and their investments within it, as he “made the audacious move to reject these earlier versions…and to inaugurate, as the central metaphor of his work, not slavery versus some mythical state of nature (as those from Hobbes to Rousseau had done earlier), but slaves versus masters, thus bringing into his text the present, historical realities that surrounded it like invisible ink” (846). On this view, despite Hegel’s denatured and idealized account of the movement of recognition between master and slave, he is praiseworthy in more significantly introducing the social and historical context and reality of their situation than previous thinkers. However, it remains to be seen if this furnishes an account useful for understanding the real, concrete social tensions caused by issues such as racism and colonialism.

As discussed previously, the quintessential movement of the Hegelian account of the master-slave dialectic is the seemingly paradoxical reversal in which the slave is revealed to have power over the master: “But as the dialectic develops, the apparent dominance of the master reserves itself with his awareness that he is in fact totally dependent on the slave” (Buck-Morss 847). The slave, previously subjugated to a lack of recognition and thinghood, likewise reverses their direction and emerges as having more social authority than the master in that they “achieve self-consciousness by demonstrating that they are not things, not objects, but subjects who transform material nature” (Buck-Morss 848). As Jinadu puts it there is a “symbiotic nature” in the dialectic, as “work or labor” in Hegel’s picture is a “vehicle for the liberation” of the slave, essentially due to their relationship - primarily economic - with the master, which results in a scheme where the master and slave “depended on each other and recognized each other’s consciousness” (78). Though Hegel does not elaborate more on the positive developments of the recognition of the slave, Buck-Morss argues given her historical interpretation that “the inference is clear. Those who once acquiesced to slavery demonstrate their humanity when they are willing to risk death” for example through resisting laboring for the masters, “rather than remain subjugated” (848). She remarks in her footnote that the consequences of such a view would be immense for the reception of the dialectic, which usually is understood as leaving the slave entirely materially grounded without a picture of their self-conscious freedom and experience: “I am suggesting that the arguments of several black scholars, which they believed to be in opposition to Hegel, are in fact close to Hegel’s original intent” (Buck-Morss 848).

However, there are reasons to believe that Buck-Morss’ defense is not sufficient to fully vindicate Hegel’s account of the master-slave dialectic, as she herself dedicates much of the latter half of her study to his conservative turn in later works, in which “Hegel repeated the banal and apologetic argument that slaves were better off in the colonies than in their African homeland, where slavery was ‘absolute’” (859). These latter arguments cast some doubt on Hegel’s intentions in constructing the master-slave dialectic and his commitment to the sort of revolutionary ethos that Buck-Morss identifies in the journals coming out of Haiti. In addition, while Buck-Morss does much to defend the saliency of Hegel’s process and the importance of his historically based argument for the history of philosophy, her claims do little to defend the actual correspondence between the recognition achieved for the slave in the dialectical argument versus in real social life. Notably, the argument which Hegel relies upon for his account of slavery, and later apologetic for it, is one which is dependent upon an idealized and formal conception of the relationship between masters and slaves and would be easily refuted through actual phenomenological accounts of the historical experiences of those who were enslaved. The idea that the slaves were “better off” could be understood as proceeding from what Fanon will describe as Hegel’s naïve understanding of the slave as free in their material labor; such a happening is meaningless and entirely inconsequential in the actual condition of achieving freedom from subjugation, as the slave cannot alienate or claim objects, both physical and cultural, as their own, given that their foundation and ownership lies with the master. Additionally, as we will see in Fanon’s critique, there is no distinction between the absoluteness of slavery in one place versus another, as its effect on the psychological condition is totalizing and affects every aspect of a self-conscious presence in the world as a particular self and identity.

Fanon’s Postcolonial Critique of Recognition

With these complications in mind, we may now turn to Fanon’s critique of the master-slave dialectic in Black Skin, White Masks (BSWM) to see whether the modifications and defenses raised by Buck-Morss help Hegel weather the refutations. Fanon’s argument is a cultural, historical, and psychological account of the self-consciousness of Black Caribbeans in the aftermath of slavery and colonization, in which he argues that the position of the colonized subject is one of dependency, a sort of resentful lashing out at the other as a result of their being subjugated: “Every position of one’s own, every effort at security, is based on relations of dependence, with the diminution of the other. It is the wreckage of what surrounds me that provides the foundation for my virility” (164). The structure of recognition far from finding itself resolved in mutual reciprocity instead emerges as a mangled relationship to the other “who corroborates him in his search for self-validation” creating an atomized and individualistic culture where “each one of them is” and “each one of them wants to be, to emerge” (Fanon 165).

The essential insight from Fanon is that the history of racism, colonialism, and slavery does not merely disappear through realizing one’s capabilities as a self-conscious agent, but rather is left incompletely resolved when these struggles are not worked out within the social realm in which they occur. Rather than allowing a genuine movement of self-creation and decolonization of society in the aftermath of these horrors, the colonized are subjected to another form of mastery by the colonizers as they are inducted into a world of values which are not their own, Fanon’s depiction is worth quoting at length:

The upheaval reached the Negroes from without. The black man was acted upon. Values that had not been created by his actions, values that had not been born of the systolic tide of his blood, danced in a hued whirl round him. The upheaval did not make a difference in the Negro. He went from one way of life to another, but not from one life to another. (171)

Fanon remarks that in the case of the Caribbean, “he went from one way of life to another, but not from one life to another.” We may understand this as their self-conscious form of recognition staying unchanged in the movement out of slavery and colonization, as it is still one which is dependent upon the master. Whereas the physical condition of life changed, the conditions of meaning-making in the society did not, leaving little sense of self-actualization or expression of desire for the colonized. In the context of the Phenomenology, this appears as an even more decisively Hegelian observation, that what matters is not just the conditions of one’s life, but the way in which that life is taken up as a form of self-conscious actualization. As Hogan characterizes Fanon’s claim here, “Blacks are not masters not because they do not own slaves, but because they do not set their own values, but simply adopt the values of whites…The master abides by norms of his own choosing” (9).

Accordingly for Fanon, the uncertainty and lack of outward conflict in the transition out of slavery puts the Caribbean in a position of being unable to acquire recognition: “For the French Negro the situation is unbearable. Unable ever to be sure whether the white man considers him consciousness in-itself-for-itself, he must forever absorb himself in uncovering resistance, opposition, challenge” (173). The struggle for recognition, far from being simply resolved in the slave’s relationship to their material labor, object, or independence of will in comparison to the master as in Hegel, becomes precisely more pronounced and intense given the now structural inability to define themselves in a world which is not their own.

It is sometimes difficult given Fanon’s mixture of his own prose with that of Hegel’s to distinguish his reconstruction of the Phenomenology’s arguments and the introduction of his own reinterpretation, what Turner refers to as BSWM’s “myriad appearances (masks) or voices” (67). However, in a footnote Fanon clearly explicates what he understands as the textual distinctions between his and Hegel’s vision of the master-slave dialectic.

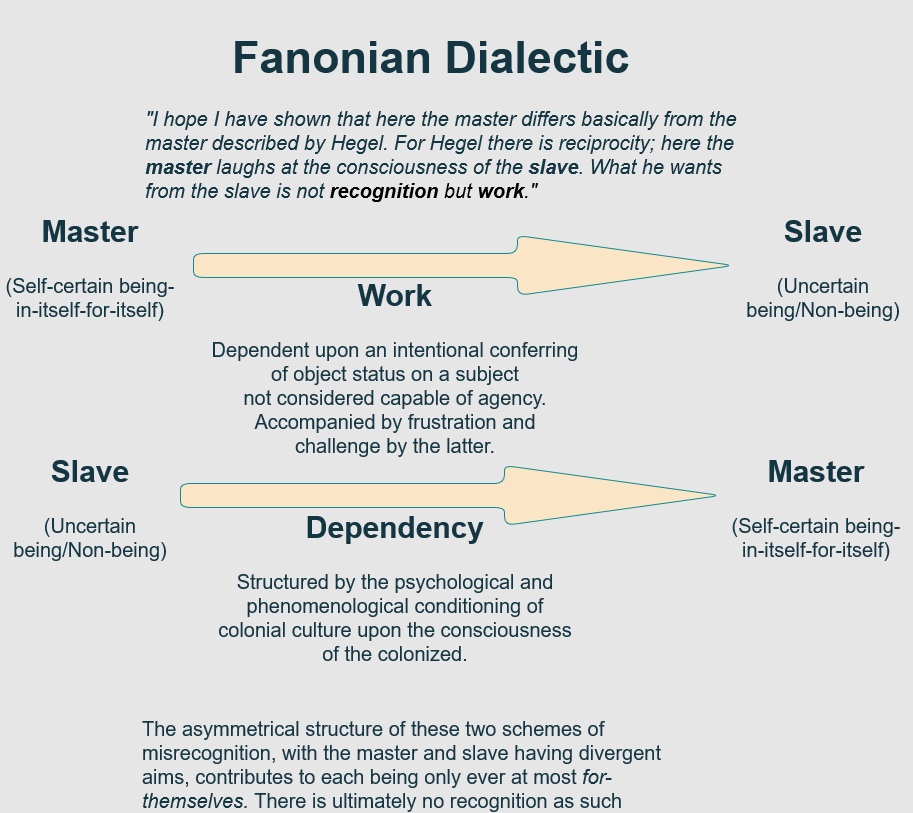

In the case of the master it is different because “for Hegel there is reciprocity; here the master laughs at the consciousness of the slave. What he wants from the slave is not recognition but work” (emphasis mine 172). Whereas in Hegel because of the idealized picture present in the dialectical argument of the Phenomenology there is a presumed, rational equality between two self-conscious agents, there is no such presumption of equality in the real thoughts of masters towards their slaves according to Fanon.

Parallelly, there is a difference in their accounts of the slave, as for Fanon: “The Negro wants to be like the master. Therefore he is less independent than the Hegelian slave. In Hegel the slave turns away from the master and turns toward the object. Here the slave turns toward the master and abandons the object” (172). Rather than understanding the slave as having an unmediated relationship with objects, they are always filtered through their social condition of engaging those objects as things to be used for labor in service of the master. What arises then is not a victory for the slave in their emergence as capable, self-conscious agents in their engagements with the material world, but rather a reactionary suturing to the consciousness of the master which figures itself as having self-asserted freedom.

It is for this reason that Fanon introduces Nietzsche’s conception of reaction as a degenerate form of agency and activity as a proper form of expression of one’s selfhood, as it allows a positive development for the slave outside of a dialectical reliance on the master. In this sense Fanon gestures towards exceeding Hegel: “Man’s behavior is not only reactional. And there is always resentment in a reaction. Nietzsche had already pointed that out in The Will to Power. To educate man to be actional, preserving in all his relations his respect for the basic values that constitute a human world, is the prime task of him who, having taken thought, prepares to act” (173).

Badenhorst has pushed back against the so-called “shared-humanity” understanding of Fanon’s critique of Hegel, especially through references to Kojève’s interpretation of the master-slave dialectic. In my attempt to clarify a vindication of the decisively Hegelian account of the dialectic in the Phenomenology, as supported by the historiography of Buck-Morss, I ultimately disagree with the Badenhorst and coincide with authors such as Van Haute, Honenberger, Ciccariello-Maher, and Gordon’s in upholding the thesis:

That is, in Hegel's dialectic, we get a human-to-human scene in which each person knows the other as like themselves. This assumption makes the master-servant dialectic inapplicable to the racial-colonial context insofar as this context is defined by a fundamental asymmetry between the two parties. (Badenhorst 322)

As demonstrated by my sketch of Fanon’s argument above, I concur with the shared-humanity explanation of his critique of Hegel as stemming from a decisively asymmetrical account of the struggle for recognition. Unlike Hegel’s account, there is a complete severance of reciprocity between the master and the slave, and they emerge as having different standards of power, recognition, and hence agency. Each struggles for a completely different resolution, despite both attempting to secure their own power. As Fanon summarizes the asymmetry in his own words: “For not only must the black man be black; he must be black in relation to the white man. Some critics will take it on themselves to remind us that this proposition has a converse. I say that this is false. The black man has no ontological resistance in the eyes of the white man” (110).

According to Villet, not only does Fanon take “reciprocity to be a key element in Hegel’s recognition,” he further “considers absolute reciprocity to be the foundation of the Hegelian dialectic” (48). The Hegelian master-slave dialectic fundamentally fails on Fanon’s account because “recognition that is one-sided cannot work,” and it is only through mutual recognition that “the search for an authentic identity, and meaning to life” can flourish (Villet 48). Furthermore, this struggle of the slave against being made an object “drives the desire for subjectivity,” and in turn “opens up the possibility of independence, freedom, agency, and personhood” (Villet 49).

We are therefore left with doubt about Buck-Morss’ claim that the struggle to death is an example or explication of an essence of a real historical event, that of the resistance of slaves in Haiti, and that “the goal of this liberation, out of slavery, cannot be subjugation of the master in turn, which would be merely to repeat the master’s ‘existential impasse,’ but, rather, elimination of the institution of slavery altogether” (849). It is precisely upon this point that Fanon’s critique comes to bear upon both Hegel and Buck-Morss’ defense, as the slave, in their psychological battle, precisely does have the goal of “subjugation of the master” which repeats their “existential impasse,” though not in terms of physical domination. The slave is still dependent upon their resentment of the master, and it does not lead directly to “elimination of the institution of slavery altogether.” In fact, Fanon’s insight is that the physical chains of slavery in the Caribbean are passed over for an even more maleficent form of psychological slavery. As the slaves are dropped into a world which is not their own, which does not correspond to their values, and are therefore up against the white odds at all times.

However, if we are to follow Buck-Morss’ sympathetic reading of Hegel’s master-slave dialectic as furnished with some material from the real happenings in the Haitian revolution, we may still find in Fanon insufficiencies in such an account. Given the neutered features of the historical characters turned into idealized objects of argument in the Phenomenology – from the master-slave, to the naïve empiricist, to the figures of the French Revolution, there are numerous examples – it is difficult to imagine it captures the true dimensions of the self-consciousness of an actual slave or of a colonized subject. That is aside from Hegel’s own limited perspective and context, as even if Buck-Morss’ account of a more radical youthful Hegel with a liberal eye towards slavery is to be taken as fact, he still later turned towards the dogmatic European racism of his contemporaries and would not have known much if anything of the thoughts of the enslaved.

In this vein, another example of Hegel’s anachronistic depictions of slavery appears in the zusatze – student transcripts of lectures – of his Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences (§163). This shines further light on the distance his dialectical method leads him away from the realities of the colonial situation. In Hegel’s eyes, contemporary debates regarding “why slavery has disappeared in modern Europe” were unnecessary as the answer was present in “nothing but the principle of Christianity itself” (§163). On his account, Christianity constitutes “the religion of absolute freedom” and the only spiritual system through which “man in his infinity and universality” is truly realized (Hegel §163). Here Hegel gives a succinct and simplified explanation of the relationship between the master and the slave. In the situation of enslavement “what the slave lacks is the recognition of his personality” (§163). The master does not recognize the personhood and agency of the slave and instead considers them “as a thing devoid of self” and as such “the slave himself does not count as an ‘I,’ for his master is his ‘I’ instead” (§163). In contrast to the Phenomenology, in which the dialectic must continue in progression towards a more comprehensive and liberatory form of consciousness, here the dialectic is halted at the point of subjugation for the enslaved. The picture here is Kantian, in that it turns upon the inability to achieve personality in the form of reason, or the “I” of self-consciousness, rather than the inability to be interpersonally recognized. Following the lack of upward movement for the slave, there is no accompanying depiction of the failure of the master’s path to mutual recognition. As a result, Hegel’s argument in the Encyclopaedia appears paternalistic and characteristic of what Buck-Morrs identifies as a conservative turn in his later ruminations on slavery. The description is structured around the slave’s individual failures and the problem is not the colonial and enslaved situation, which is an unacceptable and untenable structure for the master to perpetuate, but rather the slave’s inability to secure personality, which stems from the acquiescence to the substitution of the master’s consciousness for their own. Unlike the Phenomenology there is no description of the movement away from this insufficient concept to a more rich depiction of the slave’s freedom and the master’s deficiency.

The Phenomenology of Flesh

Through Fanon’s critique of Hegel we may find a positive development of his own approach to phenomenology. Whereas Hegel believed the dialectic reached definite conclusions and securely resolved the tensions of contradictions in absolute knowledge, thinkers such as Fanon demonstrate the continuously critical demands of phenomenology in order to achieve its aims. It is intrinsic to an understanding of phenomenology as historically and socially grounded that it remains what Heinämaa, Carr, and Aldea describe as a “permanently critical endeavor” (1). A critical phenomenology must tackle “the conditions for the possibility of experience and thinking” within the context of “the colonized, or wretched of the earth” to borrow Fanon’s language (Heinämaa et al 3).

Nelson Maldonado-Torres has explored how Fanon’s rejection of traditional methodologies in BSWM constitutes a decisive moment in his critical recasting of the relationship between the psychological and the phenomenological. In Fanon’s vision, these are intimately interwoven, as the phenomenological inflects the ideologies, such as racialization and colonization, manifest in the psychological, and vice-versa. In turn, there is no purity of phenomenological analysis or concepts, they are always grounded in, and demonstrated or contradicted by, the fickle and empirical psychology of the individual. The emphasis on methodology in thinkers such as Hegel and Husserl attempts to construct an apparatus of observation from which completely objective and apodictic observations can be made, which later phenomenologists such as Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, and Fanon recognized as folly and uncritical. As Maldonado-Torrez puts it, these thinkers make brute the reality of the question that methodological rationalists do not want to consider: “What if the complexity of ‘phenomena’ turned to be such that it defied this primacy of method?” (436).

In pursuit of this project to restore the dynamism of methodology and its responsiveness to social phenomena, Fanon develops the concept of “sociogeny” in contrast to the “ontogeny” that Freud developed through his insistence “that the individual factor be taken into account through psychoanalysis” (13). In ontogenic descriptions, it is a matter of how one’s subjectivity and personal experience brings about the developments and beliefs peculiar to the individual. However, for Fanon “the black man’s alienation is not an individual question” as racism and coloniality are a societal product which cannot exist in, nor be produced by, a mere individual. Thus Fanon describes sociogeny as a “sociodiagnostic” that recognizes “society, unlike biochemical processes, cannot escape human influences” and that “man is what brings society into being” (13).

A sociogeny of the situations of coloniality found in Caribbean slavery necessitates what I describe, following Fanon as well as Merluea-Ponty, as a phenomenology of flesh, the corporeal character of the consciousness, especially self-consciousness, of the subjugated. This also involves a positive movement, towards a humanization of the subject whose experience, previously inarticulable in Hegel’s phenomenology of spirit, finds itself a grammar in the movement towards a phenomenology of flesh. In moving from the idealist mind to the phenomenal flesh, the horizon for discussion for issues such as colonialism, racism, becomes deeper and richer. As does the possibility of the reintroduction of psychology, psychoanalysis, and psychiatry, as were Fanon’s mixed academic methodologies, into phenomenology, which before him in the tradition of Husserl were in many respects asked to be bracketed in the epoché.

Fanon frequently invokes the imagery and language of the flesh, which I take to be indicative of his philosophical and methodological disposition in relation to phenomenology. Fanon sardonically argues that it is prevalent “in Martinique to dream of a form of salvation that consists of magically turning white” and that here “you have Hegel’s subjective certainty made flesh” (44). In this construction, Hegel is identified with whiteness and Fanon demonstrates his critique of the abstraction present in the Phenomenology, that it must still be made into flesh. In the case of racialization there is a movement of being “made flesh” which materializes and objectifies the abstract and subjective spirit. The self-constitution of the phenomenological subject is undone when faced with the reality of the racial constitution of the colonized by their oppressors. As a result, for Fanon, it is when humanity is “digging into its own flesh” that it flourishes in the pursuit “to find a meaning” (11).

The evocation of flesh furthermore alludes to the influence of Aimé Césaire on Fanon, whose words from Discourse on Colonialism begin BSWM. In Césaire’s Notebook describing his return to his native Martinique after his studies in France, he remarks that the place is an intrinsic part of his existentiality: “I would arrive sleek and young in this land of mine and I would say to this land whose loam is part of my flesh: ‘I have wandered for a long time and I am coming back to the deserted hideousness of your sores’” (Césaire 17). In characterizing the land as having sores, he invokes the fleshy character of reality, as held together by the tissues and sinews of the experiences and relationships of those who are corporeally present in it. For Césaire, the phenomenological itself has the character of flesh: “To you I surrender my conscience and its fleshy rhythm”(54).

Returning to Fanon, there are resonances and inheritances between his phenomenological arguments and use of the rhetoric of flesh and the thinking of Merleau-Ponty. Fanon attended Merleau-Ponty’s lectures while in Lyon and refers to concepts from the Phenomenology of Perception (PP) throughout BSWM (Macey 126). For example, the body schema becomes complicated as a historico-racial schema, which I see as laying the foundation for Fanon’s concept of the flesh. As Macey notes in his biography, while the books of thinkers such as Merleau-Ponty and Sartre “are obviously not treatises on racism” nevertheless “they provided tools that were much better suited to the analysis of ‘the lived experience of the black man’ than Marxism or psychoanalysis” (126). Therefore turning to phenomenology, and a critique of its dominant historical and contemporary figures in Hegel and Merleau-Ponty, conformed neatly with Fanon’s goals.

In this stream of intellectual history, the Fanonian phenomenological project may be understood as going beyond Merleau-Ponty’s critique of Husserl’s emphasis on mind through the introduction of the body in the Phenomenology of Perception. Fanon’s ideas in many respects may be taken to anticipate and further Merleau-Ponty’s later developments on flesh in The Visible and the Invisible (VI). In the early Merleau-Ponty, the corporeal is still rendered bare, or neutrally constituted, and ignores the way it, and the phenomenal writ large, are always conditioned by society. Thus, Fanon pushes us towards the flesh, the sentient compound of bodily corporality and mental consciousness, which is always present in and conditioned by the world, which is in turn itself a flesh that is historically, socially, and relationally constituted.

Khalfa has argued for deep resonances between Fanon’s conjuration of the concept of flesh and Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenological turn towards the body. According to Khalfa, the view that the body is a “condition for the constitution of the given as world” was definitional to “the intellectual world of Fanon’s formative years, a world fundamentally influenced by Husserl’s phenomenology” (43). With a phenomenology of flesh, neither the disembodiment of Husserl nor the asociality of the early Merleau-Ponty are possible, as the experience associated with the flesh is always bound by temporality and spatiality; it always draws connections between our individual existential flesh and the common metaphysical flesh of social life. These two senses of flesh are univocal in that they are intrinsically related and constitutively inseparable, actually distinct but nevertheless expressive of the same material, in the same voice, as an identity without sameness. As Deleuze puts it, “the essential in univocity is…that [Being] is said, in a single and same sense, of all its individuating differences or intrinsic modalities. Being is the same for all these modalities, but these modalities are not the same” (36).

For example, in valorizing the heritage of the Caribbean people Césaire identifies them with “flesh of the world’s flesh pulsating with the very motion of the world!” (37). The idea of the “flesh” of the “flesh of the world,” describes acutely the two senses of flesh: the first is the existential flesh of the corporeal embodiment of a single human being, the second is the metaphysical flesh of the constitutional relationality which grounds our reality and forms the condition of possibility for our individual existence. These two senses of flesh are univocal in that the existential and the metaphysical are truly identical with, and inseparable from, one another. They constitute two distinct expressions of the singular dynamic flesh of reality that is actually absolute and total.

In turning to Merleau-Ponty’s writings on flesh, I do not intend to reduce Fanon’s account of the flesh to the concept’s description in The Visible and the Invisible. To do so would not only be anachronistic, given its publication in 1964 over a decade after BSWM, but disingenuous to the project here of taking seriously Fanon’s voice as a phenomenologist speaking from a specific situatedness as a Francophone thinker. Rather, I find the affinities between these two thinkers to be a way to bring into greater vision Fanon’s depiction of the flesh, its relationship to the critique of Hegel’s phenomenology, and its genesis of another methodological direction.

In Merleau-Ponty’s late phenomenology, “the flesh is simply the ‘in-between,’ the space mediating the distances of seer and seen” (Ngo 158). The flesh is therefore not the seer or the seen themselves, but the mediating space or the socio-historical field of experience, which constitutes subject and makes their recognition possible. In Fanon’s drawing upon the flesh in response to Hegel’s dialectic, we see him decrying the abstract space – the view from nowhere as Charles Mills and George Yancy have said – upon which it unfolds. It is backgroundless, it presents a seer and a seen without reference to the in-between which constitutes the relationship that makes their interaction possible. Therefore flesh may be characterized as “a thickness, a lining, or a tissue,” and hence Merleau-Ponty maintains that it “is not a thing, but a possibility, a latency” (Ngo 158). The flesh is therefore not merely our individual existentiality but also our shared common metaphysicality, not only the shown skin of my body, but the meaning of that skin in the phenomenological and socio-historical context in which it is seen.

Therefore, against the Hegelian picture, the terms and consciousnesses of the dialectical argument can never be temporally or phenomenologically abstracted from how they are actually experienced. There is in fact no true moment, or event, in which we are entirely in-and-for-ourself or in-and-for-another, these are always intermingled and intertwined possibilities of the flesh. Put differently, the racialized subject demonstrates the inconceivability of an out-of-body experience.

In a famous example, Merleau-Ponty describes our perception of the color red as constituted by – and only possible because of – a constellation of meanings which spread across space, time, society, culture, and history (VI 132). This is precisely the space of the flesh which demonstrates how concepts such as race may only be understood in an existential and intrinsically social context. As Merleau-Ponty puts it himself, in a manner which may be taken to poignantly critique racial colorblindness and objectification, “a visible, is not a chunk of absolutely hard, indivisible being, offered all naked to a vision which could be only total or null, but is rather a sort of straits between exterior horizons and interior horizons ever gaping open” (VI 132).

With the concept of flesh in Merleau-Ponty and Fanon, a subject’s entanglement in flesh – as in the historico-racial schema – is the condition for the possibility of their being, or their being perceived. There are sinews which connect the self to culture, to society, concepts which become animate and vital in our bodily activity. For example, when an individual makes it a habit to carry a book, something meaningful is added to one’s perception of them beyond merely an additional entity or object. He carries a bible, he must be a believer. They carry a textbook, they must be a student. She carries a pamphlet, she must be a revolutionary. These sinews are the connections between our flesh and our experiential worlds. In the same way, the perception of race is not possible without the socio-historical condition of racialization and coloniality. When a racialized subject – any social subject – perceives or touches another, or themselves, flesh touches flesh, in the sense not only of two individual bodies, or existential fleshes, but also in that one touches metaphysical flesh, the very fabric of coloniality and raciality which one is conditioned by and in turn is conditioning. The flesh captures the problema and possibility of racialization and coloniality in a way that the spirit, and even the body, cannot.

Conclusion

We may understand Fanon as subjecting the Hegelian master-slave dialectic to a thoroughly historical critique. In one sense, especially in terms of Fanon’s exposition which skillfully manipulates Hegel’s jargon, he is attempting to critique him from within his own philosophical register and systematicity. As Hogan puts Fanon’s indebtedness to Hegel’s phenomenology, “Fanon explicitly relies on Hegelian premises to establish two distinct claims about Blacks and whites in the Francophone world” (10). By redrawing the master-slave dialectic with the collective cultural experiences of the Caribbean in mind, Fanon reveals the insufficiencies of Hegel’s still idealized picture of recognition and the ways in which only the real, concrete experiences of consciousness can reveal the process of recognition unfolding in an actual society. The project of phenomenology possesses much that is fruitful for social and political critique. However, such an approach cannot fall prey to the same methodological blunders as those present in Hegel himself, and must instead take the idealized theory of recognition and reground, rearticulate, and reapply it to the content of real experiences in the context of their identity, society, and history.

This approach involves a decisively Fanonian turn, but is influenced by the materialist criticisms of Hegelianism that have long been championed by Marxists. As Turner poetically explains the insight of a Fanonian conception of recognition through flesh: “The idea that ideas must hear themselves speak determines the way we must grasp them as inherent in our lived experience” (67). Or as Merleau-Ponty puts the importance of corporeality in history when discussing Marx’s critique of Hegel: “It is true, as Marx says, that history does not walk on its head, but it is also true that it does not think with its feet. Or one should say rather that it is neither its ‘head’ nor its ‘feet’ that we have to worry about, but its body” (PP xxi). If Merleau-Ponty illustrates that Marx’s materialism did not go sufficiently beyond Hegel’s idealism in its analysis of history, and posits the need for a turn to corporeality, Fanon in turn demonstrates the need for phenomenology to proceed fully into a socio-historical account of flesh. Following Fanon, we must direct ourselves always towards a sociogeny which neither walks on its head nor thinks with its feet, but rather takes the flesh of the world, the subjectivity of the individuals and collectivities which occupy it, as the beginning of its observation of phenomena and their genesis.

Bibliography

Aching, Gerard. “The Slave's Work: Reading Slavery through Hegel's Master-Slave Dialectic.” Theories and Methodologies, Volume 127, Issue 4, 2020.

Badenhorst, Daniel. “Fanon, Hegel, and the Problem of Reciprocity.” Hegel Bulletin, March, 2022.

Bird-Pollan, Stefan. “Hegel’s grounding of intersubjectivity in the master-slave dialectic.” Philosophy & Social Criticism, Volume 38, Issue 3, 2012.

Buck-Morss, Susan. “Hegel and Haiti.” Critical Inquiry, Vol. 26, No. 4, Summer, 2000.

Césaire, Aimé. The Original 1939 Notebook of a Return to the Native Land: Bilingual Edition. Translated and edited by A. James Arnold and Clayton Eshleman, Wesleyan University Press, 2013.

Cole, Andrew. “What Hegel’s master/slave dialectic really means.” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, Vol. 34, No. 3, 2004

Deleuze, Gilles. Difference and Repetition. Translated by Paul Patton, Columbia University Press, 1994.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. Translated by Charles Lam Markmann, Pluto Press, 2008.

Forster, Michael. “Hegel’s dialectical method.” The Cambridge Companion to Hegel, Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich. The Phenomenology of Spirit. Translated and edited by Terry Pinkard. Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Hegel, G.W.F. The Encyclopaedia Logic (with the Zusätze). Hackett Publishing, 1991.

Heinämaa, Sara. David Carr, Andreea Smaranda Aldea. “Introduction: Critique – Matter of Methods.” Phenomenology as Critique, Routledge 2022.

Hogan, Brandon. “Reading Fanon on Hegel.” Philosophy Compass, Vol. 18, Issue 7, 2023.

Honenberger, Phillip. “Le Nègre et Hegel”: Fanon on Hegel, Colonialism, and the Dialectics of Recognition.” Human Architecture: Journal of the Sociology of Self-Knowledge, Volume 5, Issue 3, 2007.

Jinadu, L. Adele. Fanon: In Search of the African Revolution. Taylor & Francis, 2003.

Khalfa, Jean. “My body, this skin, this fire: Fanon on Flesh.” Wasafiri, Vol 20, Issue 44, 2005.

Macey, David. Frantz Fanon: A Biography. Picador Books, 2000.

Maldonado-Torres, Nelson. “Frantz Fanon and the decolonial turn in psychology: from modern/colonial methods to the decolonial attitude.” South African Journal of Psychology, Vol. 47, Issue 4, 2017.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. The Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by Colin Smith, Routledge Classics, 2002.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. The Visible and the Invisible. Northwestern University Press, 1968.

Mills, Charles. “‘Ideal Theory’ as Ideology.” Hypatia, Volume 20, Issue 3, 2005, p. 173.

Ngo, Helen. The Habits of Racism: A Phenomenology of Racism and Racialized Embodiment.

Nigel, Gibson. “Dialectical Impasses: Turning the Table on Hegel and the Black.” Parallax, Volume 8, No. 2, 2002.

Ogungbure, Adebayo. “Dialectics of Oppression: Fanon’s Anticolonial Critique of Hegelian Dialectics.” Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies, Vol. 12, No. 7, 2018.

Patterson, Orlando. Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study. Cambridge University Press, 1982.

Pinkard, Terry. Hegel’s Dialectic: The Explanation of Possibility, Temple University Press, 1988.

Turner, Lou. “Frantz Fanon’s Phenomenology of Black Mind: Sources, Critique, Dialectic.” Fanon, Phenomenology and Psychology, Taylor & Francis, 2022.

Villet, Charles. “Hegel and Fanon on the Question of Mutual Recognition: A Comparative Analysis.” The Journal of Pan African Studies, Vol. 4, No. 7, November 2011.

Von Kleist, Heinrich. The Marquise of O– And Other Stories. “The Betrothal in St Domingo.” Translated by David Luke and Nigel Reeves, Penguin Books.

Weate, Jeremy. “Fanon, Merleau-Ponty, and the Difference of Phenomenology.” Fanon, Phenomenology, and Psychology, Routledge, 2021.

Whitney, Shiloh. "From the Body Schema to the Historical-Racial Schema: Theorizing Affect between Merleau-Ponty, Fanon, and Ahmed." Chiasmi International, Volume 21, 2019.

Whitney, Shiloh. “Affective Intentionality and Affective Injustice: Merleau-Ponty and Fanon on the Body Schema as a Theory of Affect.” The Southern Journal of Philosophy, Volume 56, Issue 4, 2018.

Yancy, George. “Forms of Spatial and Textual Alienation: The Lived Experience of Philosophy as Occlusion.” Graduate Faculty Philosophy Journal, Volume 35, Issue 1/2, 2014.

Yancy, George. “Charles Mills: On Seeing and Naming the Whiteness of Philosophy.” The CLR James Journal, Volume 28, Issue 1/2, 2022.

Notes

- The pictures included in this paper have been developed using artificial intelligence. I have manually superimposed text from Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks on the latter two.

- I will use the terminology of master and slave in consistency with the commentary of Buck-Morss and Fanon. However the English text of the Phenomenology cited here uses the term servant in lieu of slave. The original German uses Herrschaft and Knechtschaft which have been variously translated as master-slave, lord-bondsman, or lordship-bondage.

- For other discussions of Fanon’s critique of the Hegelian dialectic, see Gibson, Honenberger, Ogungbure, or Villet.

- Forster describes Hegel’s dialectic as “a method of exposition in which each category in turn is shown to be implicitly self-contradictory and to develop necessarily into the next” (132). In another case, Pinkard describes the dialectic as based upon the thesis “that the basic incompatibilities of classical philosophy” are only surface level and therefore “can be reconciled by enlarging the categorical context in terms of which the original opposition was framed” (19).

- A contemporary example in 19th century German literature of depictions of the self-consciousness of the colonized is Heinrich von Kleist’s short story “The Betrothal of Santo Domingo,” in which a freed slave violently rebels against his former master at the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution, much to the confusion of the narrator.

- As examples Buck-Morss references two critiques of Hegel’s account of the slave in the dialectic: Paul Gilroy’s interpretation of Frederick Douglass’ claim that the slave would prefer death to enslavement and Orlando Patterson’s theorization of social death and criticism of labor’s liberatory potential (848).

- Andrew Cole’s influential essay has argued that discussion of enslavement is misguided as the dialectic describes the feudal situation of lordship and serfdom. However, the similarities between Hegel’s two depictions provide evidence, in my view, of its relevance to slavery.

- In distinction to the elements of the body schema which are provided by our perception, in the historico-racial schema these are provided “by the other, the white man, who had woven me out of a thousand details, anecdotes, stories” (Fanon 111).

- For detailed treatment of the relationship between the philosophies of Merleau-Ponty and Fanon, see the recent work of Whitney or Weate.

Cite this Essay

Brown, Grant. “Phenomenology of Flesh: Fanon’s Critique of Hegelian Recognition and Buck-Morss’ Haiti Thesis.” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, no. 40, 2024, doi:10.20415/rhiz/040.e03