Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge: Issue 37 (2021)

The brain is a blinding light: How neuroscience (re)plays a parody of The Solar Anus

David R. Gruber

University of Copenhagen

Abstract: This essay turns to Georges Bataille’s The Solar Anus to expose the brain of the contemporary neurosciences as a parody. The brain plays the light of consciousness illuminated in the penetrating glow of the brain scanner but cannot recognize itself in the brightly colored image. Bataille’s critique of Western philosophy and its pursuit of totality amid helpless partiality and mindless materiality proves fitting to today’s “neuro-everything.” The essay ends with the suggestion, following Bataille, that scholars and artists can perform the parody to push neuroscience to pore over its repressions and re-gear its penetrative pistons on transformative action, pursuing a creative study of bodily generativity, the only visible alternative to the solar anus of blinding light.

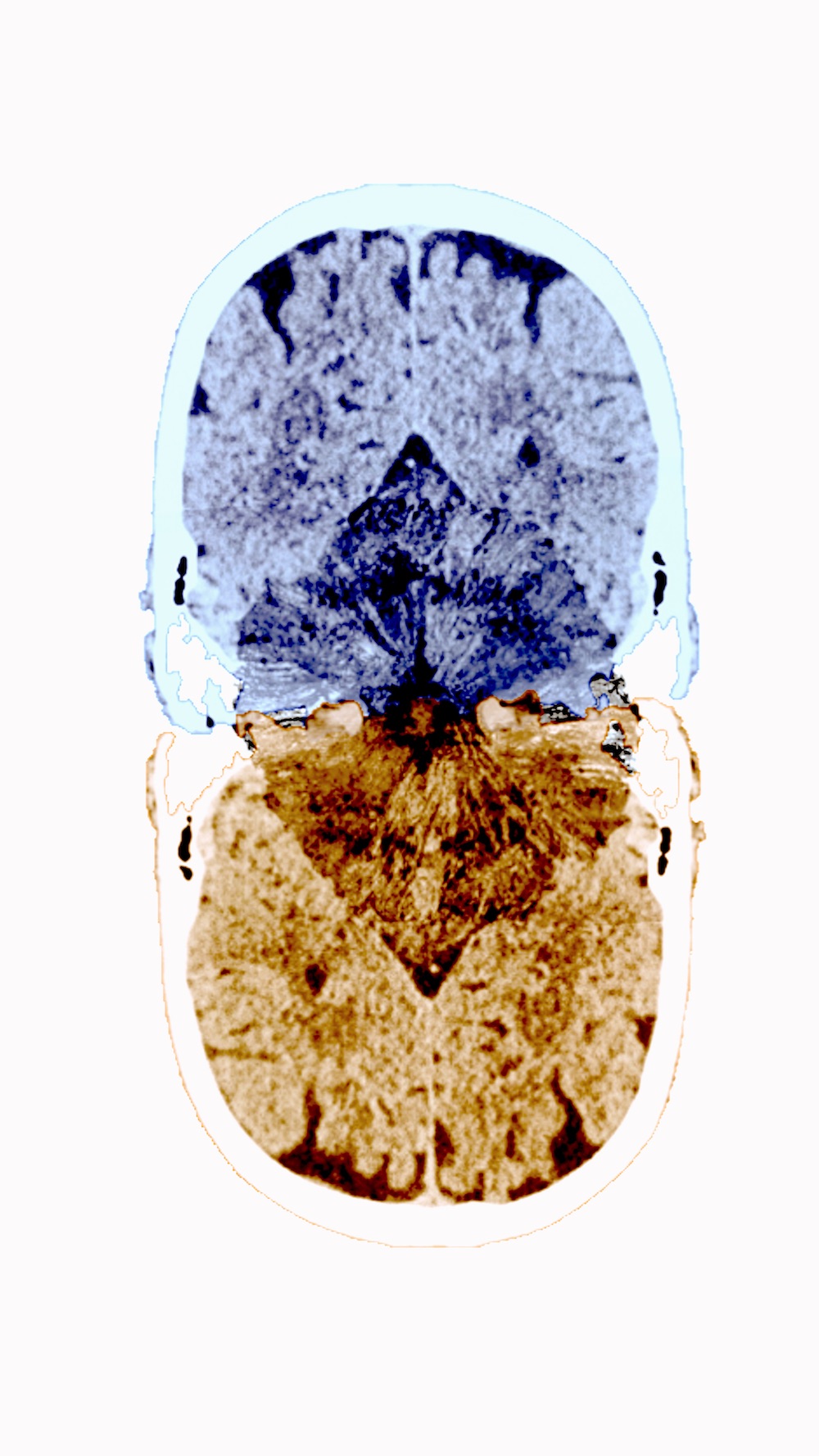

Anyone familiar with Georges Bataille’s (1931) work The Solar Anus can immediately venture a guess as to the title. The brain as a blinding light signals a brain over-exposed and parodying itself when illuminating its flesh as the light of consciousness in the brightly colored image constructed by the suffocating black hole of the brain scanner. The brain begs for more real and ever greater exposure of a processural existence in static representations of itself. The brain searches for some connection between the body and experience while yet claiming to be both one and the same. In this, the brain calls up from the grave Bataille’s insistence that philosophers and artists alike “slavishly invert” their own ideas and “their power is turned upon itself as self-destruction” (Grindon, 2010, 306). Neuroscience seems a good example as the motive is to explain the totality of human experience through only what is seeable and countable, but the practice ends up always looking around for something else to count, demanding the light of physicalism while never illuminating the first-person experiences of brain states. Mentalizing makes a mockery of microscopic neuronal mapping. Affective outbursts exceed the analytical lens. Consequently, although upheld as the disciplinary embodiment of objective data, the neuroscientific brain, as “The Brain” of authority, winds up being composed as Man, a mirror, an addict, and a psychopath.

The inescapable reflex of intellectual reversals gestures toward a bodily condition that parallels the brain’s assertion of superiority and independence from the body. That is to say, the trap of the academic parody that Bataille highlights in The Solar Anus also exposes a body fashioned by environments while walking about the earth as if independent. The walking itself, the mechanics of the animal, the tromping around the mucky pond, and the eating and the breathing, of course, undermine the delusion of independence. The body seems to absorb this broader parodic situation when it opines to open and expose itself to an outside while simultaneously clinging to its own fleshy repressions that seal it off and allow it to protect an experience of cohesion and definition.

A body runs from vulnerability but becomes more vulnerable in the process, since there is nowhere to go that is exclusively inside of itself and only more world to encounter. Ignoring the conundrum, the body becomes a parody. It favors the embarrassing belief that it can secure itself, if it just keeps monitoring its developments in a more and more technical and deliberate fashion. In The Solar Anus, Bataille points to the flushing red cheeks of the humiliated face as a performance in skin likened to the embarrassment of building self-destructive human concepts. The ontology-as-parody that Bataille so loves foregrounds the anus as the hidden, ugly underside, an image supposed to be embarrassing. But as a parody, an essay like The Solar Anus already soils its pants and tumbles face-first into a bucket of manure so that the ass is left straight up in the air for all to see. After the violent prat-fall, Bataille knows, the actor will jump up and look around with shit dripping down his face to remake the situation; the atmosphere of the theater can never be the same.

As an artist, Bataille would have admired, I think, Andy Warhol’s later work—especially when understood as a form of elitist taunting from within—even if the dominating abstract expressionism more common in Bataille’s lifetime certainly resonated with his work insofar as it “collapsed the distinction between the gestures of creation and those of destruction” proving to be a kind of artistic-philosophical counterpart (Grovier, 2020, para 13). Bataille, I am confident, enjoyed the flicking of Pollock’s paint and the feeling that materiality and rhythm, body and energy could be united in aesthetic and affectual bliss to run amuck over idealist obsessions with capturing light and depicting nature. Painters who squatted over the canvas releasing momentary flights and aggressions surely performed what painting as expression always held within it and repressed, what it always wanted to be. The splashing act parodied a history of substance painting. Yet, those wild canvases, too, once read as images of “genius” and corralled as confessionalist interpretations of long held family angers also became parodies of what they hoped to achieve (See: Cotter, 2006). Previous artworks courted their own undoing through foregrounding neatly arranged shapes and dots, but Pollock’s unruly canvas, too, would pave the way for its own destruction. Being so damn singular and composed out of his cute East Hampton farmhouse, the canvas undeniably ushered forward the flash bulb pop of the realist mass production grid of hard materiality coming from urban New York City socialite artists like Warhol (See: Maguire, 2006).

Considering the elevated elitism and raucous rivalries and playful revelries of 20th Century art, it is probably unsurprising that Bataille’s work—between the 1930s and 1950s primarily—finds parody as most potent for overturning reigning social orders. The performance, of course, is another replay of the same embedded inversion, but the shock and the laughing confronts a materialist stage and releases the catharsis of the play. Another composition can flow forth as a result—but only from bodies aware of the terms of engagement and outside of the high intellects that grind themselves and others down with their unshakabilities. For Bataille seems to communicate that those dreadful suits are doomed to tumble over their own technical terms like big feet and asses whose serious shoes and black dress pants fall down because the belt broke for being too strained. Too many yummy deserts, we suspect. What the people want, as Jimmy Cliff (1981) said, is “reggae music”—a beautiful rush of feeling in a world something of their own. The world is, after all, pressing on us with feeling after feeling after feeling haunted by funeral processions of the technical, the logical, the perfectly ordered interpretation, which rings over us like a four-year-old’s cymbal band of the more real. The hall is filled with enraptured listeners nodding along to the clanging music and saying, “Wow, sounds just like me!”

For Bataille, the anus, as an inversion of the face or a falling-in, is an antagonism and a historical repression useful because it is operating, as he tells us, like the glorious bright sun, which we desire to look at and indeed cannot ever really see, but we do always feel (5). We wait on it to tickle us or to explode. The sun as an anus is a dangerous object in The Solar Anus threatening our extinction at any moment, able to expunge social orders of propriety, just as the sun can destroy every living thing in a wave of sudden radioactivity. The sun, in this, way parodies its Being as life-giver. The universe exists in a circle along with humanity’s ironical, self-opposed miscalculations. The sun as a volcano may erase the solar system with a release of energy even if it presently cultivates the earth and, indeed, keeps it perfectly spinning in orbit. The sun embeds in all, a material core, doing no less than giving the feeling of what life itself is, which is something outside of the sun. Here, the sun is an image of the body. The light and the darkness, the heat and cold, the over and again of day and night, up and down, forge psychological incursions from an ontological spin of seeming ridiculousness. A prison of pure parody.

I exhale and animate the living connections that Bataille makes, which look to me to be waiting like suspended bodies for resuscitation in the brain-bodies of the contemporary neurosciences. The brain as the organ of life, like the sun, can destroy us at any moment, consigning the body to senseless freezer meat without notice. Those bodies-as-brains want to laugh. They need to laugh at themselves bending over to face the expulsion of the rumbling stomach, the feet tingling with Covid-19, and the deep breath of dumpling steam not captured in the fMRI image set out on the kitchen table. Who can see that solar anus? Brains should laugh when hearing from their lovers about the relegation of the Self to sets of neurons firing. Who can hear such rude smelling chatter? Neuro-revolutionaries could use a good giggle at a human lifeworld crammed into to 4X6 image. The brain scan should certainly have a bright red face over its stultifying reductionism. But, of course, a brain scan has no face. A brain scan has no body. A brain scan displaces the entire body for the machinic representation of the Anterior cingulate cortex, so the scan, as a scan, cannot look ashamed even if it whispers in optimization algorithms, noise reduction calculations, and data smoothing procedures that its body is always outside of itself.

I see in Bataille’s essay a description of how neuroscience functions today and suggest playfully that The Solar Anus helps us to consider present technical repressions. So I awaken a thread of Bataille’s thinking, making an inventive return of something haunting, writing performatively to foreground his work as well as the action of “Critical Neuroart,” or the dramatization of neuroscience with a “cheeky parody” that can “throw open self-conscious and ironical impressions of scientific realism” that function to “create tensions between the self and neuroscientific knowledges” (Gruber, 2020, 125). The essay intends to elaborate an ironical celebration—like the perpetually cheering drunkard careening toward his own self-destruction—highlighting as absurdist theater the flirty idea that the brain illuminates human existence. I expel, like the violent anal eruptions of the volcano, any idea that brain imaging technologies integrate biological information into formations of self. Believing that imaging technologies bake biology into unbothered “information” exhibits a lovely piece of birthday cake with “Congratulations” scrolled on top in sugar frosting. Once presented to Donna Haraway, she cringes at the cake and sobs for not getting what she told everyone she wanted. To break the unease of the scene, a Hollywood health guru stands to sell “The Natural” as a packaged, sugary breakfast cereal proven to make you feel better from very bright brain scans of fourteen white, college-aged males living in New Jersey. So I wonder whether something irreverent and untraditional can help us to see what to do about all of this. I end the essay by leaking out the contemporary neurosciences in the form of hot evaporation so that the rain might go back up into the sky and condense as sexy clouds and pour down fast again in a cycle that parodies wet and dry seasons.

The brain as a solar anus

The brain as a solar anus is another entrance to a world “purely parodic... each thing seen is the parody of another, or is the same thing in a deceptive form” (Bataille, 1931, 5). The brain as a solar anus is another institutional delineation, another technological application, another normalization, another brain remaking an image of itself as an erasure of what it purports to illuminate. The brain as solar is a blinding vision lending no sight, a violent love of the Self that fucks a body unknown to it and totally hidden in the bright white darkness. In this way, the brain as a solar anus is a body staring blank-faced into the sun.

The brain as a solar anus is the irresistible attraction of gravity to a massive black hole of the fMRI scanner like “Ton 618” that expels all matter seemingly from nowhere—nowhere within sight—generating the incessant fascination to probe it, to penetrate it, to see what’s really, truly happening. The brain as a solar anus is a Sisyphean effort at capturing a totality well beyond any body. In the contemporary mind, the brain bubbles up sexual excitement at a body on a quest for complete exposure, a compulsion formed of the Capitalist imperative to expand ever outward into all possible realms beyond all boundaries as much as an affect flowing out from the environmental fluidity of the body itself. The quest chases the closest possible impossible, wanting like the paparazzi to catch a fleeting movie star in a flashbulb. But there is nothing to be seen in meat’s ontological blackness but the penetrating light of the Sun, the blinding vision.

The brain as a solar anus shines too brightly. The pinpoint of white light is where the breaking through of the piston generates the instantaneous feeling of eating “thingness”—an Adam and Eve apple grown in a sanitary lab and given with a promise of opening the eyes to what it really means to eat. The white lab coat, bleached so bright, legitimizes the taboo act of opening the anus and going in with radiating hopes and twinkling values. The Night of the anus is always, as Bataille (1931) says, where “the Sun directs its luminous violence, its ignoble shaft” (8). In following the Night around the earth, the Sun aims to force its light on the Night, but like the neuroscientist desperately lighting up the brain for Truth, the vision always just escapes its power of exposure.

The Egyptian creator god Ra is not a neuroscientist because he is the god of both horizons. Ra is better a representative of the universe itself. But tired of the endless sunshine at the beginning of time, humankind plots against Ra to instate itself as the sun. We note that Ra triumphs, and humans are left with the endless cycle of day and night. We forget that the tiring return of the seasons is a clue to keep balanced in the absence of Ra. But humans never listen, mesmerized by the light, closing eyes to sleep at night and trying to forget it ever happened.

Perhaps, no one is surprised then when the brain appears in the Self-help section of the bookstore where the Self is a parody of itself, made to be smooth and calculatable in stunningly reduced discourses of a blinding vision, like the way astrologists talk about the future. Nor is anyone surprised when the brain appears suddenly in the museum through the aestheticized representation forged from one second detection of oxygen moving through a thin slice of brain tissue and then discussed as really the artist, a parody of humanity, of art, and of human creativity. Nor is anyone surprised to encounter the brain announced in the gym where the body sculptor needs guidance on how to grow physically stronger by penetrating the “core” motivational substrate while never thinking about what drives the endless effort to look like Superman. The Sun is parodied by the darkness, and the darkness follows the Sun.

The scanner as a sex piston

Scanners are the sex pistons, of course, just as the tree grows to the sky to penetrate it but crumbles eventually to the earth having never reached the stars. The sexual motion, up and down, makes the earth rotate, like the wheel and piston of a locomotive, as Bataille (1931) tells us (7). As sex piston, the scanner pushes inside of the brain, ever deeper, and moves out and then back in again with force. The banker and the publisher, the cook and the trainer, the scientist and the professor alike demand another push inward, another shove. The brain as tissue resists, pushing out, but the back and forth over time builds the momentum of the locomotive. This unending action as a determinism as a drive as a dedication to more, more, more, more, more is as disturbing as all the paper ads, flyers and catalogues stuffed into the mailbox and burned every week in the fireplace.

The momentum is magnetic resonance, a sexual exhilaration at a secret rave, like the movement of the train with the rush of going somewhere amid added confusion about what is streaming by the window fast in a blur. The confusion grows with the speed of action. Eventually, the speed becomes another body that appears in bed, Bataille tells us. The boy touches this other body while harboring “the mental darkness that keeps him from screaming that he himself is the girl who forgets his presence while shuddering in his arms” (Bataille, 1931, 8). The image, once the function of the brain scanner and its effect on the scanned, enacts in the body the same reciprocal, generative movement that Bataille suggests animates the form of all things. As Neil Gamble and Nail (2020) say when peering into outer space, “black holes are neither passive matter nor empty voids but active processes” (v). Or, as Bataille says: the anus is a volcano of the earth (7). The brain and the Sun, the scanner and the piston are productions but also parodies that transform each other.

The turning around and the going through—these sexual movements set aside so as not to be seen even as they are everywhere in markers and material goods—instigate the inevitable, and ever ironic, crumbling of the obelisk and the rotting of the tree. Rationality cannot sustain itself. The patient in the bed of the scanner whose brain sparkles in bright red and blue blobs, “falls asleep as empty as mirrors” (Bataille, 1931, 8). The indeterminancy is matter, and the fluctuation a perpetual escape. The brain is a solar anus.

The brain as a blinding light

How does this work, in practice? A team of neuroscientists—to take but one example—watch on an electrical wavelength machine as a neuron fires in a monkey’s brain when that monkey performs a specific grabbing action. The same neuron fires when the monkey watches one neuroscientist perform what looks to be a similar action. The neuroscientists then gather over coffee and cake, raise the shades of the lab to let in some sunshine, and ask what this means (See: di Pellegrino et al., 1992; Gallese and Goldman, 1998). Looking for the light in the lit up screen showing a brain lighting up only defined areas, the answer developed is that the monkey’s brain is subconsciously “simulating” the visual field, or “mirroring” its environment automatically, which makes sense because brains operate like computers and because mirrors are embedded in the myth of Narcissus, which is the story of “us” anyhow, like the narratives of Lacan that make human development a mirroring of the body and, thus, make a social-body right from the beginning of body awareness (See: Mambrol, 2016). So the neuroscientists land on “simulation” to be the means of production of the monkey’s own “understanding” of the action. The specific meaning of that action is relegated elsewhere, a decision made when looking at other scans of other brains and needing to stand in the light that they shed. Theorizing additions to basic “mirroring” from “higher order” systems of “processing” make it really jam and bake in some room for other labs’ taste for brains (Wolf et al., 2001; Tkach, Reimer & Hatsopoulos, 2007).

In this case, what we have are “simulations” as understandings, a parody of understanding. We have, more jarringly, a noun: “mirroring people” (Iacoboni, 2008). We also have shocking revisions of archeological histories so that brains, as mirroring machines, explain now the “foundations of civilization” (Ramachandran, 2010). All of this explodes out from going in to penetrate a brain, all from a single neuron recording, all from a monkey’s brain. The Sun swings fast around in orbit—more, more, more! What we soon have are children diagnosed with Autism now called “broken mirrors” (See: “Mirror, mirror,” 2007). In being “broken,” the children lack simulation of visual fields, and in lacking simulation, they lack movement between “higher orders” and “lower orders” to create a brain capable of social understanding (Wolf et al., 2001; Jaffe, 2007). The children become parodies of children. They play, but their play is “broken,” and they see but look only ever through a cracked mirror (Iacoboni, 2008; Oberman and Ramachandran, 2007). The mothers who call them “broken mirrors” and remake their brains as mirrors spend lots of money on therapies from mirroring neuron interpretations. Here, mothers become parodies of mothers as they spin around and nurture not children but brains and not brains but mirrors and not mirrors but broken mirrors and not broken mirrors but psychoanalytic dreamscapes and cups of coffee.

All of this erupts suddenly, a volcanic expulsion from the anus, when another neuroscientist says that the mirror is a false image, an empty reflection of those who mirrored each other’s body movements while drinking too much coffee in the light of the morning. The actual, more real foundation of mirroring is “predictive processing” (See: Kosonogov, 2012; Hickok, 2014). What we have then is prediction in subconscious time because brains are like computers, and prediction is what gamblers do to represent the future. Because brains make representations. Put a big bet down on the brain; it does pay off. But we forget: the house always wins. So we play once more only with a parody of prediction when saying that prediction is what complexity does with large sets of information, like what scientists do. All of us, after all, watched the buffalo run across the meadow and made a good guess—to the lake they go for a drink! The lake is a remnant of a volcanic explosion now filled with water and dark as Night. This is like saying that the Sun will rise tomorrow. The Sun does rise, and it is blinding.

The neuro-everything as something else: Inverting Bataille and the brain

Searching for some motive in the light, squinting through its beams, we say that the material and the social and the symbolic are for Bataille a productive synthesis. No declared state of Being is independent of experience with what it is like to live. Any process ontology—whether flowing from Bataille or Deleuze or Haraway or Butler—has a pragmatic impulse, seeking after accomplishment in the study of co-development and closer attunement in environmental co-feeling. Once seen as a reaction to histories of metaphysical substance, the process becomes another parody. The contours of Things are contours only in a reigning consensus about how Things are; the generative dynamic creates a concept only from a classification; the human-independent forces being pursued are found with human hands and felt in human hearts. In this, Bataille laughs at process philosophy as much as metaphysics, at science as much as mysticism. The effort of The Solar Anus is to mock “an impossible achievement: that of arriving at ‘a total identification’ and a ‘transcendent whole’” (Boldt-Irons, 2001, 355). So the rolling of the Sisyphean rock mocks Cartesian dualism, rigid orders of hierarchical thinking as much as it mocks Aristotle’s categories and neuroscience. Given that the parody for so many years now has been and continues to be of Western philosophy’s staunch rationalism, sucking oxygen from the Enlightenment, we are not surprised that we can turn Bataille so easily toward the brain to imagine what he might say if not so buried.

Neither are we surprised that Deleuze and Guattari (1983) invoke The Solar Anus to stress productive fulfilment and positive Becoming in contrast to a repeated reliance on categories and invocations of lack in Freudian psychoanalysis (9-10). The presumption of absence as against presence—or against a material body that apparently produces a desire to find more of itself somewhere hiding in its own physical presencing—along with the presumption that our consciousness’ is to blame for our way of being in the world—together generate a new alliance, which is not formally a re-visitation of an old Deleuzian machine. The tangle of absence and consciousness is a locomotive, surely, but this is not a Platonic engine exactly. It is not really a genetic body anymore either. The present hallucination and delirium pumped out by this machine is the brained body, or the brain as body.

In the “neuro-everything” of today, every association of the body is a brain. Books like Spiritual Practices for the Brain certainly do a lot of good for spirits, but nobody quite knows how the brain was able to get the acting job of the mind—in the theater being run by the Catholic school of all places! The brain, surely, has in no way proven qualified for the job. A nun raises a hand and asks whether the brain deserves to be the headliner. Then another nun asks where the body went or if there is a second volume soon to be released for bodies. “Got to attract the crowds,” a priest yells out from the back row. “Cast the brain.” The body giggles at the scene while waiting behind the stage curtain. It seeks its perfect moment of entrance to stun the audience. The body intends to take the show back with a big prat fall. At the least, the body knows that the brain performs only as a talking head, so soon enough the brain will fail to fulfill its many promises and fade right at the moment it announces its plasticity claim. The brain, the body tells us, will ultimately end up like a lonely, fat child star trolling the nuns on social media from a Beverly Hills bathroom. We respond to the body by suggesting that they should really just team up and do an Abbott and Costello gig. The “Who’s on first” routine feels like it could be really funny if the ballfield is replaced with a neuroscience lab. But the body is steaming and won’t hear of it, not while the brain is showered in flowers.

In a neuro-everything, I think we must all admit, the brain as a brain known to neuroscience is nothing like a brain. And the scanner as a scanner known to the brain experiencing its probe is nothing like a scanner. The body lying in the bed, Bataille tells us, doesn’t know who or what it touches. So we follow the performance yet further: the brain as a brain known to the reader is nothing like a neuroscientist or a writer or a reader. And the scanner as a scanner known to the neuroscientist is nothing like the scanner or the reader.

Yet, the brain of the reader is a brain; the scanner is a scanner; the neuroscientist but a well-intentioned independent explorer. Consequently, we must ask if we are getting fucked. Are we going anywhere? Of course! The locomotive chugs along, and we feel its rush. We open our mouths and suck the exhilaration. Whether or not the probe is indecent, whether or not the Sun overcomes the Night is another parody of the Sun and the Night, a reciprocal movement of the circle and phalloid sketching an image of its own revisionary trajectory and return. This is where we must laugh.

There is no escape from oscillations, but there is intensity. There is being consumed. There is a brain and no brain, a brain and not a brain, a brained body and a body that is a tree. The “Schizo” as Deleuze and Guattari (1983) say, “is as close as possible to matter” (19). The inauguration of neuroscience will be strangeness. The path for the scientists is to become egg-heads, as they may well have been called when children dissecting frogs. The taunt is a parody, since Deleuze and Guattari hope to themselves become eggs; as they say, the egg “is crisscrossed with axes and thresholds, with latitudes and longitudes and geodesic lines, traversed by gradients marking the transitions and the becomings” (19). The brain is an egg like the brain in the glass case in the science museum just like the brain on drugs cracked in the frying pan infused with Nancy Reagan’s haunting specter. Shall we see if the brain now becomes more delicious or disgusting? Add some salt over the white, hot glair bubbling over the white, hot flame and eat your brain that is an egg. Smile at yourself like the egg and bacon face with Mickey Mouse pancake ears looking up from your plate and smothered in syrup and fed to you by your mother when you were five after being called down from a magnificent oak tree while catching a trail of ants and then look down at the plate and see in the yolk of the egg how insufferable are the requirements of technicity. Who can eat a breakfast like that with tweezers? Pick up the big spoon, no use your hands, all in; there is no spoon. There you go, the harrowing experience of the nomadic “neuro-everything,” which is always something else entirely.

If nothing else, getting into the circus ring of ring-around-the-rosy materiality is solidarity with those being labeled future psychopaths and abnormal lobes, addicted selves and hyperactive dis-orderlies. The chuckle makes a funny face at a neuroscientist, a face that looks a lot like the one made when excreting mirror neurons after the stomach ache from consuming the psychological exclusion of the misunderstood. But excrement is better than smashing the glass of the mirror with a fist; in that event, we couldn’t see the face we are making. Better than buying a new brain in a blueberry brain drink that rushes down the toilet in an uneventful flush right before you ask for your money back only to be met with looks of disdain mirroring your own. There is no catharsis there.

Where Critical NeuroArt really comes into play, where it really makes its name is not in throwing a party for the negative reply but the affective power of the parody of human action followed by a personal pardon for all involved. An arm around the shoulder. A feeling of mutual admiration in the nonsensical celebration and backstabbing joke. Nobody feels too bad waking up to the sunshine, even if it interrupts the dream. Soon the warmth of the light spreads over the body. The sun always rises again and always evaporates the frost and the rain when it does. So we should try to laugh at how unsettled we felt while getting wet and having nowhere to hide from the storm and wanting to run back into bed. The relief and good feeling is, itself, an inversion of the violence in The Solar Anus.

We have no choice but to make Bataille’s work a parody of itself as well. We must laugh at how seriously it takes a condition that it is also subject to. Filthiness and repression by domineering regimes is enacted in the work as violations of dirty bodies with a “morbid reflex” of revolution, which seems to ask the audience for another inversion, for a turning back on the darkness (Bataille, 1931, 8). Maybe Bataille truly desires a positive, happy reflex. Because his essay dramatizes greed as filth and sexual violation as Capitalist violence, he invites the reader to condemn the intentionally naughty illustration. The work, as parody, then, suggests that he hopes that the readers will become hypocrites and parodies of themselves in the act of condemnation. The conditions that he points toward, in other words, are what deserve the condemnation; nobody who bothers fussing about the text will be worried about solving them—too caught up in maintaining polite society and, thus, too unable to see how the condemnation sustains the conditions of social repression that existed prior to his text. Presumably, the offended are the very powers that feel sustained by the removal of the shock at such conditions offered in a legitimately shocking way.

Yet, some scope of undecidability, we must remember, lingers in Bataille’s work. Thus, it should also contain the means of its own undoing, have a second-guessing implicature, which causes us to doubt our own reading of Bataille as much as the condition of slavery he calls to our attention. We wonder, in that case, how Bataille’s work actually cooperates with Capitalist domination and filth. We can say it does in its adoption of shock and sex as attention-grabbing salesmanship. Perhaps, it also perpetuates the objectification of universalism through constructing its own terrifying resoluteness about what life is really like in the Twentieth Century. At that point, we start to wonder if we can laugh at this text. The conditions that he describes, like his own work, are really not so funny. But perhaps we can second guess ourselves once again: Bataille’s text is so over-drawn—it must set out to undo itself like a funeral comedy. Maybe it is a “What have the Romans ever done for us?!” kind of inversion, a laugh born of its own obvious oversights and dismissals of patently plain commonalities, philosophically of the transcendental or the metaphysical. What has a reliable, describable reality ever done for us?

Surveying the vision of death, decay, and human waste in The Solar Anus’ trapped parodic materialism, the reader detects an unrecognized insistence on Truth in life’s moving reiterations, a real spiritual repression. The circle that The Solar Anus cannot escape parodies its own construction of meaningless return. Imagining Bataille’s soul swirling in that text somewhere, we feel a body desperate to recapture its losses, combating them with the reassertion of continual loss but also having no ground to stand on, except the turn to nature as a world of parodies and ironies from which a claim that anything has been lost seems nonsensical. We must, in other words, if we take Bataille seriously, believe that he laughed his ass off when reading Nietzsche while letting the tears roll down his red cheeks. So we must, if we take him seriously, be willing to turn around and feel the heat evaporate from the text and rise up with it to the clouds where the atmosphere grows thin, and there, we can cool off and get a sense of the whole picture of parody—right while we ourselves critique his efforts to map out totalities of existence.

Neuroscience’s persuasive power, sweating with technical, scientific, innovative, entrepreneurial, and genius revolution, would surely benefit from a good cool down. Climb up the mountain, enjoy the view, see what fades and what gets lost in the snow. The unexpected form cannot appear unless the world falls asleep for a long while and forgets how the lab works and how the Human Resources department runs the show with its three-dimensional grids of performance evaluations. In this image of closing the eyes, I pray that we can reverse the role of the day and night to make the unconscious state the new priority for knowing and the environment the affective bath of psychology. The unseeing body cuddles the overexposed brain with love despite the brain’s disdain for its many contributions, its open-endedness, its permeability.

So if you look at a brain scan and see a blinding light, then feel the moment as a freedom for the body—because whatever exists beyond the moon and stars, as Socrates says in Plato’s cave analogy when speaking of the escaped philosopher who looks up at the ideal world of the sun, is far out even past the sun, which blinds us with its light. At that point, you can really see it: the blinding light is your place in the world. Turning away, there is only darkness. Then the parody of Bataille becomes suddenly clear: the darkness is punctured suddenly by the light of the stars, which glow like harbingers of a hope crying out that this world is but an inversion of another; every world can be inside-out or have another hiding inside of it; there is certainly more to see. Why not use a brain scanner to look for it?

One wonders whether someone out there near one of those midnight stars stares back at us with the same feeling that they themselves face unknown worlds in the night that are but a glimmer and yet a magnanimous undoing of everything they’ve ever known—or perhaps they’re thinking the opposite, wondering why we can’t see what is so obvious: we are blinding ourselves while living in worlds upon worlds upon worlds of light having endless spans of illumination. Laughing would not be an unnatural reaction to the wonderment of it all. But then again, neither would crying or praying. But if we are praying, then we are not really doing so with brains but with our hands and knees and hearts, a whole posture, both physical and sensational and indescribable, prostrate out on the ground, smelling the damp earth that grows what we eat. When facing the ground in that way, we know not whether it is day or night. We do not care because we do not need the light to see ourselves, and the darkness does not hide us.

References

Aydin, C. and de Boer, B. (2020). Brain imaging technologies as source for extrospection: Self-formation through critical self-identification. Phenomenology and the cognitive sciences. Online first, March 26. Accessed June 14, 2020.

Bataille, G. (1931). The solar anus. Visions of Excess: Selected Writings, 1927- 1933, Ed. and trans. A. Stoekl. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1985.

Boldt-Irons, L.A. (2001). Bataille's ‘The solar anus’ or the parody of parodies. Studies in 20th Century Literature 25 (2, A3). https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1507

Byrd, D. (2019). Hefty black hole holds new record for high mass. 8 December. https://earthsky.org/space/astronomers-discover-heaviest-black-hole-abell85-nearby-universe.

Cliff, J. (1981). Give the people what they want. (Track list 2, Vinyl release), WEA International Label Inc.

Cotter, H. (2006). Jackson Pollock at the Guggenheim: works of swirls and pixie dust. The New York Times, 26 May 2006.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1983). Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

di Pellegrino, G., Fadiga, L., Fogassi, L., Gallese, V. and Rizzolatti, G. (1992). Understanding motor events: a neurophysiological study. Experimental Brain Research 91 (1), pp. 176–180.

Gallese, V. and Goldman, A. (1998). Mirror neurons and the simulation theory of mind-reading. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2 (12), pp. 493–501.

Grindon, G. (2010). Alchemist of the revolution: The affective materialism of Georges Bataille. Third Text 24 (3), pp. 305-317.

Grovier, K. (2020). ‘Blinding Light’: The great American painting? BBC, 5 October. https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20201002-blinding-light-the-great-american-painting.

Haraway, D. (1989). Primate Visions: Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science. Routledge: New York and London,

Hickok, G. (2014). The myth of mirror neurons: The real neuroscience of communication and cognition. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Iacoboni, M. (2008). Mirroring people: the new science of how we connect with others. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Jaffe, E. (2007). How we reflect on behavior. Association for Psychological Science. May 1. https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observer/mirror-neurons-how-we-reflect-on-behavior. Accessed June 14, 2020.

Kertz Kernion, A. (2020). Spiritual practices for the brain: Caring for mind, body, and soul. Chicago: Loyola Press.

Kosonogov, V. (2012). Why the mirror neurons cannot support Action Understanding. Neurophysiology 44 (6), pp. 499–502.

Maguire, E. (2006). At Jackson Pollock’s Hampton’s house: A life in splatters. The New York Times. 14 July.

Mambrol, N. (2016). Lacan’s concept of mirror stage. Literary Theory and Criticism, April 22. https://literariness.org/2016/04/22/lacans-concept-of-mirror-stage/. Accessed June 14, 2020.

Neil Gamble, C. and Nail, T. (2020). Black hole materialism. Rhizomes 36. http://www.rhizomes.net/issue36/gamble-nail.html. Accessed June 14, 2020.

Oberman, L.M. and Ramachandran, V.S. (2007). Broken mirrors: A theory of Autism. Scientific American. 295 (5): 62-9.

Ramachandran, V. S. (2010, January). The neurons that shaped civilization [video]. TED Talks. Retrieved from http://www.ted.com/talks/vs_ramachandran_the_neurons_that_shaped_civilization.html. Accessed June 14, 2020.

Science Daily Staff (6th November 2007). Mirror, mirror in the brain: Mirror neurons, self-understanding and Autism research. ScienceDaily. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/11/071106123725.htm. Accessed June 14, 2020.

Tkach D., Reimer J., Hatsopoulos N.G. (2007). Congruent activity during action and action observation in motor cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience 27(48): 13241–13250.

Wolf, N.S., Gales, M.E., Shane, E., & Shane, M. (2001). The developmental trajectory from amodal perception to empathy and communication: The role of mirror neurons in this process. Psychoanalytic Inquiry 21(1), 94–112.

Notes

- Aydin and de Boer (2020) make an argument for integrations of biological information into people’s concept of Self; this essay is not a reply to them, since their argument explores how people use biological narratives to describe themselves. This piece comments on the biological in a messy, spewing, ontological mercury river and sugar cola sense, like the Elvis peanut butter banana sandwich smashing Blue Hawaii into Honduras into additives of gospel and guitar solo blues to make rock n’ roll palatable right there on Beale Street in 1954.

- Haraway famously and wonderfully articulates the unending investment of the social into the scientific. See as an example: Haraway, 1989.

- The reader can find more about Ton 618 in Byrd, 2019.

- Shakespeare’s sonnet 18 compares “Thee” to a “summer’s day” too hot for its own good; what lasts, the bard proclaims, are “eternal lines,” the poem’s lines as striations of earth and Thee’s contribution to life’s endless aesthetic.

- See: Kertz Kernion, 2020.

- For a script of the sketch, see: Who’s on first, by Abbott and Costello. Baseball-Almanac. https://www.baseball-almanac.com/humor4.shtml.

- As far as the author knows, the phrase “neuro-everything,” was first used in the following book chapter: Furnham A. (2011). Neuro everything. In: Managing People in a Downturn. Palgrave Macmillan, London.

- “What have the Romans ever done for us?” is a quote from the satirical Monty Python’s Life of Brian film, produced by HandMade Films and Monty Python Pictures, 1979.

- See: Plato, The Republic, Book VII. MIT Classics, online. http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/republic.8.vii.html. 26 September, 2020.

Cite this Essay

Gruber, David R. “The brain is a blinding light: How neuroscience (re)plays a parody of The Solar Anus.” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, no. 37, 2021, doi:10.20415/rhiz/037.e02