Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge: Issue 35 (2019)

As follicles fall

Haute coiffure & deconstruction

Darren Tofts

You could never quite look like Tony Curtis in the movie The Sweet Smell of Success… making you almost willing to kill for that haircut

——Niall Lucy

“Serendipity,” Greil Marcus reminds us in Lipstick Traces, “is where you find it” (Marcus, 1989, 93). And it was serendipity that played an unexpected role in the composition of this piece. I had been dipping into Kirby Dick and Amy Ziering Kofman’s book based on their 2002 film on Jacques Derrida. Fascinated by the scenario of a philosopher having a haircut, a writing of sorts strutted out some preliminary ideas. But while doing so I realised my mind was stuck on a photograph. Not though of Derrida and his coiffure, but of myself (the link is not as conceited as it may seem). I, like him, have white hair, so as a way to improvise the text, I wanted to find a photograph of myself from behind taken some years ago. But I had no idea where it was. The quiff I am sporting in it is almost identical to his. It is unusually tidy, trim, also suggesting a recent haircut. Then it happened. One of our kittens had accidentally knocked a book off a shelf next to the chair in which I was sitting. I say accidentally with confidence as I’m pretty sure that The Satyricon of Petronius is not part of their curriculum. I opened it out of habit and there it was, Darren par derrière.

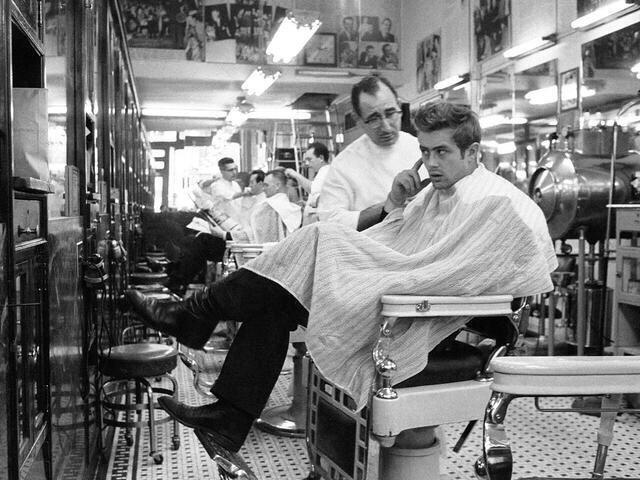

Cut to a salon de coiffeur, Ris-Orangis, Île-de France, sometime in 2005. In Derrida the film the daddio of deconstruction sits in a barber’s chair. Framing it there is a slow, considered reading of an abridged passage from Derrida’s 1982 book on Nietzsche, The Ear of the Other, by Amy Ziering Kofman. The tenor of the voice is cautious, gently spoken. The sample from the text, about the biography of a philosopher, is relevant to the scene. A vernacular, ordinary event, Derrida is simply having his hair cut rather than professing. What is really captivating though is the cinematography. After a close up of the cutter gently snipping carefully garnered folds of hair, the counter-shot is taken from further back, revealing Derrida’s head receding into a mise en abîme in the salon’s mirrored wall. Clearly it is a strategic choice to sample the endless play of difference articulated, or perhaps more appropriately reticulated, as différance by deconstruction. But perhaps too it is a defined, closely framed and structured mise en scène, an image of follicle incidence.

The montage of Derrida’s visit to the hairdresser is in some ways out of place. It is a very ordinary way to locate us in his world as voyeurs of an intimate moment. It’s touching the way that the cutter gently snips shafts of his hair that drift to the floor like snowflakes. As a consciously framed close shot it is preceded by a montage of Derrida in his studio sending a fax, speaking on the phone, attending to quiet, domestic business that is not at all busy. Preceding his visit to the salon his hair is conspicuously much longer, dishevelled, professor-ish, not unlike that of Julius Sumner Miller. He too, like Derrida, explained how it is so.

The photograph of “Darren from behind” is a kind of incidence of the Derrida image, even though it precedes it by some years. He stands in a hot tub, naked, accompanied by his two then young children (known for the sake of privacy in this text as Mutt and Jeff), also naked. The shot is entirely self-conscious, staged, though coiffure is clearly not the studium here. More a happy accident, the style of hair cut is incidental to the taking of the image; the gratuitous, knowing display of posteriors for posterity is clearly the intention, not a caprice.

Derrida the film could have easily opened with the sequence of the philosopher’s visit to the hairdresser and gone on from there. But it is an incident of an altogether different kind that, while not commencing the film diegetically, rather prefaces it suggestively, as something potentially to come after the opening credits fade out:

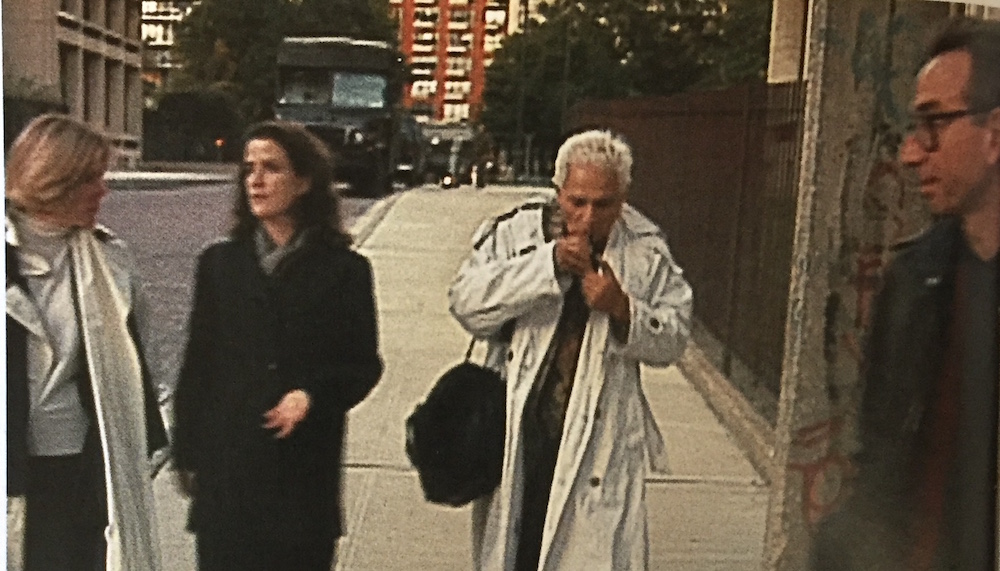

Ext. New York City — Afternoon.

Derrida and company — Professors Alan Cholodenko, Peggy Kamuf, Derrida

advance toward us, preparing to cross the street.

Prior to this convergence in New York, Alan Cholodenko had for some time been trying to entice Derrida to come and speak in Sydney in 1999. To assuage the philosopher’s concerns about the tyranny of distance, of having to transport his atoms back in time across the long haul to the Antipodes, Cholodenko’s conceit was to simply be there in New York, to casually coincide with Derrida’s presence (both were attending a biography conference). It was an ingenious conceit to demonstrate how easy it is, even gauchely retro in the age of data flows, for atoms to come together across distance in a shared time and place. Whether or not conceding it was his destiny to go to that fatal shore, or the attraction of sitting in discourse with wild colonial boys such as Terry Smith and Paul Patton, he acquiesced. All he could say, we can only hope with an affirmation as assertive as Molly Bloom’s final word in Ulysses, was “yes.” Cholodenko’s strategy had worked. Derrida came to Sydney.

Incident

“We no longer consider the biography of a ‘philosopher,’” writes Derrida, “as a corpus of empirical accidents that leaves both a name and a signature outside a system which would itself be offered up to an immanent philosophical reading” (Derrida, 1985, 5). In other words the philosopher’s biography is in fact imminent, always on the verge of becoming something other, something unexpected like an unknown visitor. In this it is easy to imagine that the Dadaists would have simply adored Derrida, not least for his outrageous coiffure (think of Max Ernst). But most of all for his daring and often anarchistic thought, the irresistible zeal of his passion for language against itself, blissfully out of our control. Like the growth of hair différance finds its own way. It is beyond and escapes the manacles of those who seek to pin it down, to attempt to make stable, accessible and communicable sense or intention, as if it were ever really possible (with the exception of the rare, accidental and fugitive times when it is). And, as if unwittingly to make the point, Derrida’s mother once asked him, surprised and a little bewildered, was it true that he had spelled difference with an “a” (Dick & Kofman, 99). Jackie again said yes.

Imagine Hugo Ball in the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich around 1915. He is, just for a change, high on absinthe. And imagine further that he has just read Of Grammatology in a perverse, quantum future tense yet to come. He is totally blown away by it. He has been deliriously lost in the following sentence for three days: “It is not enough to say that the eye or the hands speak. Already, within its own representation, the voice is seen and maintained. The concept of linear temporality is only one way of speech” (Derrida, 1997, 289). He sits on a Persian rug, gibbering and intoning at the same time, “Derri Derri Derri Derri Derri Derri Da Da Dada Derridadada Derri Derri Derri Derri Dada Derri Da Da Da Da, Derridadada, Derri Derri”... perpetuus.

Meanwhile Derrida, in an unknown zone of the continuum, sits legs akimbo in a knowing pastiche of Sir John Tenniel’s caterpillar in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Thinking of Heidegger he languidly intones, “Who are you…?” These words are directed towards no obvious addressee. Perhaps he is talking to himself. He complacently puffs hashish, blowing perfect smoke rings that temporarily make out the letters m a r t i n i h e i d e g g e r, before evaporating into nothing. This mannered spectacle is a figurative pantomime of the melancholy death of the twilight with a slow, silent, mournful pffff. Despite the heightened artifice of this phantasmagoria, there is no scent of alcohol nor evidence of the use of amphetamines. The subtle and vaporous suggestion of Marcel Duchamp’s wife Teeny invokes in Derrida thoughts of the infidelity of her previous husband Pierre Matisse and the unexpected arrival of the Other. Avid chess player like her husband, she beguiles Derrida’s soporific mind with complexity and the uncontrollable algebra of strategy, anticipating many moves ahead in a delirium that spirals his mind into the fourth dimension. His eventual submission to a tincture of dextromethorphan further intoxicates this illogic of sense into a heightened mania uncannily reminiscent of the Dervishes of Turkey. With the shade of Antonin Artaud stuck in his mind, irritating it like a demented eye mote, he ululates at speed:

castrationalwaysatstakeandtheselfpresenceofthepresentthepurepresence

(Derrida, 1981, 302)

wouldbetheuntouchedfullnessthevirgincontinuityofthenonscissionthevolume

thatnothavingexposedtherollofitswritingtothereader’sletter-

openerwouldthereforenotyetbewrittenontheeveofthestartofthegame

These words from Dissemination find their supplementary trace in an unexpected, paranoiac-critical cross-reference not from Salvador Dalí, but rather Mike Patton’s lyrics from Mr Bungle’s “Goodbye Sober Day”:

Pin my ear to the wisdom post

(Patton, 1999)

Hang me up and drain me dry

Mend my shipwrecked spirit

Lift the veil from my eyes

A stretch to be sure and without doubt in the paranoiac-critical world an outrageous conceit, but it is not as capricious as it may seem. John Donne, don’t forget, got away with comparing lovers to a pair of compasses in 1611. In both passages the cut and the scission are not acts of violence but rather a poetic of cleansing and the order of rule. Surprisingly, Derrida was not circumcised at birth, the possibility of having been so would have extended the conceit further. Patton seeks calm and release from his “inter-galactic ulcer,” a different kind of excess from the foreskin. The cutting of Derrida’s hair is an intransitive act that sustains, if only momentarily, Marcel Duchamp’s infra-mince, the infinitely small, as the trace of a thereness that is implicit in its fall, always-already sustained in the downward drift. And the fall invokes in Derrida’s mind nothing as banal as sin, penance or gravitas, but rather the unavoidable passion and transcendence of cruelty.

Mômo

Derrida’s interest in Artaud’s torturing of language was the basis of a lecture he presented at the Museum of Modern Art in 1996, associated with an exhibition of Artaud’s drawings. It was in fact a minor sensation or succèss de scandal (depending on your view), an irresolvable contradiction of which Artaud would no doubt have approved. Derrida was at odds from the start with the governors, curators or whoever was pulling the shots at MoMA. His original and preferred title that he suggested was a self-conscious, ironic gesture to both the topic of the lecture and the venue itself: “Artaud the Moma” (ix). However, much to Derrida’s chagrin, the MoMA administrators in charge of the event took immediate dislike to the title he had provided. Derrida, no doubt in a deconstructionist fit of pique, withdrew the title and in its place proffered the deliciously banal “Jacques Derrida will present a lecture about Artaud’s drawings.” So, instead of anticipated fireworks, the title was the pathetic whiff of a candle being blown out. Artaud the Mômo, the fool, probably would have seen the funny side of the slight. Regardless of the farce, the lecture proceeded and one of the world’s great scribblers spoke with sublime eloquence of one of the world’s most controversial artists:

‘Ten years since language left’: what a declaration! It announces that language left me, for it has gone and left me without it, but also, more secretly, that it left or departed from me, that it took its departure from me, by me, proceeding thus from me by the lightning of my drawing… The lightning of the mad man (la foudre du fou) passes by way of the drawing’s body, more precisely by the body of a ‘black pencil.’ (Derrida, 2017, 21).

And what a glorious fool he was:

I have to complain of meeting in electric shock dead people whom I would not have wishes to see.

The same ones,

whom this idiotic book called

Bardo Todol

has been drawing out and presenting for a little over four thou-

sand years.Why?

All I ask is.

Why? …

(Artaud, 1976, 533).

Like Derrida, Artaud did have quite the shock of hair, which had absolutely nothing to do with the electricity that he repeatedly received into his body, although he does attribute the force of his passion to being foudroyé, or “lightning-struck”; an “unnameable passion to which no other resource remained than to rename and reinvent language” (Derrida, 2017, 20). And further, as Kaira Cabañas notes, quoting Artaud in the “Afterword,” “I would like to write outside of grammar, to find a means of expression beyond words” (83).

And so he did. With Derrida’s grammatology in mind, the pictographic was another form of writing for Artaud. It was a form of inscription that spoke of the horrors, the ecstasy and the pain he experienced prior to, during and after repeated electric shock treatment. Writing, alphabetically and pictorially, was a form of riding the current, becoming part of a slipstream of energy over which he had absolutely no control: “My terrestrial life is what it should be: that is, full of insurmountable difficulties which I surmount. For this is the Law” (Artaud, 1976, 403). What, one can only wonder, would Thomas Edison have thought of all this.

And So, Back to Hair

Thinking on it, the image of Derrida having his hair cut resembles one of those stylised scenes of hair salons of the 1950s. Celebrity or vernacular, they are all pretty much the same in terms of the pose, of surly Continentals, the gestures, mise en scène as well as the fetishized gaze on follicle fashion. The armature of the barber’s chair, like something out of a Francis Bacon painting, the vertiginous mise en abyme of mirrors within mirrors of Renaissance domestic portraits, or the peacock gazing at oneself in a shop window in nouvelle vague cinema of the 50s, are all echoed in the image of Derrida having his do done. And with his thoughts on circumcision in mind from Glas, it is very much a “determining cut” (Derrida, 1986, 41).

Postscript

The Jade’s fulsomeness had so tir’d me that I began to devise which was to get off. I told Ascyltos my mind, and he was well pleased with it, for he was willing to get rid of his torment, Psyche: Nor was it hard to be done, if Gito had not been lockt up in the Chamber; for we were resolved to take him with us, and not leave him to the mercy of a Bawdy-house.

—The Satyricon

Bibliography

Apuleius, Petronius Arbiter, Longus, The Golden Asse, The Satyricon & Daphnis and Chloe, resp., London: Simpkin Marshall, Ltd., 1933.

Artaud, Antonin, The Theatre and Its Double, trans. Mary Caroline Richards, New York: Grove Press, 1958.

— Selected Writings, ed. Susan Sontag, trans. Helen Weaver, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976.

Derrida, Jacques, Dissemination, trans. Barbara Johnson, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1981.

— The Ear of the Other, ed. Christie McDonald, trans. Peggy Kamuf & Avital Ronell, New York: Schocken Books, 1985.

— Glas, trans. John P. Leavey, Jr., & Richard Rand, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990.

— Of Grammatology, trans. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997.

— Jacques Derrida: Deconstruction Engaged. The Sydney Seminars, eds. Paul Patton & Terry Smith, Sydney: Power Publications, 2001.

Dick, Kirby & Amy Ziering Kofman, Derrida: Screenplay and Essays on the Film, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005.

Lucy, Niall, A Derrida Dictionary, Oxford, Blackwell, 2004.

Marcus, Greil, Lipstick Traces: A Secret History of the Twentieth Century, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press,1989.

Patton, Mike, Mr Bungle, California, Slash Records, 1999.

Cite this Essay

Tofts, Darren. “As follicles fall: Haute coiffure & deconstruction.” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, no. 35, 2019, doi:10.20415/rhiz/035.e06