Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge: Issue 35 (2019)

Hometown Queens and Superheroes: Ari Moore’s Queer History of Buffalo

Ana Grujić and Adrienne Hill

That night in the spring of 2016 when a friend introduced us to Ari Moore, it became clear that she would quickly outdrink us. We sat in one of Buffalo’s surviving gay bars, where off-kilter cocktails compensate for trashy music and cheap liquor. In complete Sunday church lady regalia, she prophesied the impending demise of several iconic pop women performers of the younger generation, seamlessly weaving in the narrative threads of her own life. Attentive, we nodded, as if seated in a professor’s office. Earlier that winter, soon after we had founded the Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project, people informed us at every step that no substantive endeavour of collecting, performing, and archiving the queer history of this city could unfold far without Ari Moore. Even the ones slightly older than her. It’s clear to me now: not merely has Ari been part of, a witness, and confidante to much of Buffalo’s and this region’s trans, queer, and black history. She is herself a historian-performer, or if you will, a performative scholar of queer past and future.

The histories that Moore narrates, draws, paints, or imagines, are often rooted in the region of Western New York and in Buffalo, where she has spent her entire life, but they also reimagine social worlds unmoored by “the prison house” of “the here and now,” in the words of José Muñoz. While she declares herself to be a citizen of the world, she closes the same interview with: “At that, I am Ari Moore, your Buffalo transgender griot—the receptacle of the oral history of Buffalo’s transgender community. Thank you, and good night. Now, pour the wine.” Many narrative filaments and questions could unravel from here: not only the vine of immediate oral histories for which Moore tasks herself to be a repository, but also their relationship with concerted efforts to historicize and archive queer lives in the Buffalo region. The Madeline Davis LGBTQ Archive of Western New York, now under the roof of Buffalo State College, is the largest of its kind outside San Francisco and New York City. Yet, one would be hard-pressed to find in it any substantial material about even a portion of black queer history. Trans history (but not of color or working class) is slightly better documented, mostly thanks to a remarkable and lonely public presence in the 1970s and early 80s of Peggie Ames, a regional pioneer of trans organizing. And then, there is a discursive and imaginative gap between a cultural imaginary still mostly romantically stuck on the two coasts and a similarly often stuck scholarship, and a seemingly forgettable country in-between. If it deceptively shares the state with New York City, Buffalo’s queer history reflects that of other Rust Belt cities – its blue collar queers playing a crucial role in the formation of a dynamic bar scene throughout the first half of the 20th century, and in the constitution of historical queer identities. The unsutured gap leaves the differences and variations between an iconic story of a migration from a claustrophobic, backward hometown to find a queer community in a big city, and the many accounts of lives spent often by choice in these hometowns and cities, yet to be examined. Moore’s art, activism, and personal archives exist in these gaps and archival absences.

Since that night at the bar, we’ve gone to Ari with many a question and a need for a clue – a time during which we’ve grown accustomed to listening to what’s in her chuckle or her pause, as much as in the words. We are invoking here the methodology of “listening in detail,” reliant on enactments of personal memories and fictions that Alexandra Vazquez practices in her engagement of performances of Cuban music. In order to historically situate a sigh or a laugh, not as a text, barely an open-ended one, but a minoritarian critical methodology, we invite Ari Moore’s audience to embrace the cultural and critical value of the limits of discourse, while they also enjoy her humorous eloquence, her pleasure of self-narration, bearing witness to history, even when this is painful or not available to words. Much of Ari’s way of speaking back slyly or mockingly to dominant historical knowledge, in a dramatically embodied code of her fluctuating voice, an affective and improvised cultural repertoire of oral performance, is unfortunately lost in print. This is how we wish to bring in this interview, aware that really it should be uploaded as a sequence of audio and image files (the reason we offer here several audio snippets).

Clip One: “I Don’t Do Curious Straight Men…”

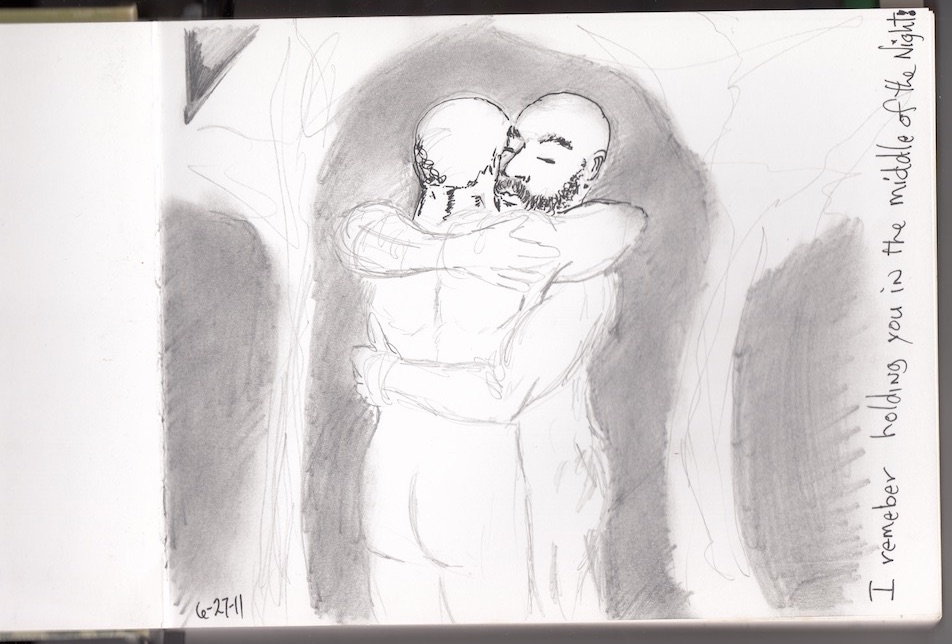

This text incorporates segments from two recorded conversations with Moore. One, in which she recounts her life and work in general, was conducted in October 2016, in her home on Buffalo’s East Side, for our Trans Oral History series. Our inaugural attempt at interviewing trans Buffalonians, much of it was experimental. We ended up with a massive audio file and only about half an hour of video footage. Moore is surrounded by her illustrations for several graphic novels, a graphic chronicle of her “trans journey,” her paintings, a photo archive preserved in many boxes, and the scrapbooks she has kept of Buffalo’s trans and queer scene spanning about fifty years. The evidence of Moore’s deep sense of the historicity of place and a nuanced understanding of how elements of subcultures travel across generations and spaces to accrue new possibilities, a meaningful portion of her archive transcends her own time, such as a reprinted photo of a young Dorian Corey, the mother of the legendary House of Corey, before she left Buffalo for New York City. Or, the breath-taking and beautifully styled 1960s and early 1970s pictures of Buffalo’s queens such as the ubiquitous Miss Wanda Cox, Ms. Cougar, Ms. Dixie (Ari’s mentor), Brandy Martini, or Ms. Jeanette, in private homes, in bars, on stages, or in dressing rooms of the long ago vanished local clubs, during performances bearing names such as “Illusions: Women Impersonators” or “Queen City Follies” (the latter with a flyer not offering an address of the venue but instructing the audience to call a private number). The second conversation was sparked by our encounter during the first interview with Moore’s illustrations. It took place several months later in our home, as the snow like hushed pillows was steadily blotting out the familiar street view. Several decades away and back, once she stopped talking and we again looked through the window – we were elsewhere.

Ari has decisively helped to shape our history project and keeps doing so, maybe less by explicit instruction (even though this has certainly happened), and more by what she projects as a critical and artistic vision of queer Buffalo over time-space. We embarked on this work convinced that the desire and stages of migrations from supposed backwaters to big coastal cities and what has transpired in them, is not the only narrative trajectory out there to be engaged in smaller cities and towns’ queer history. We were ready to discover a variety of different narrative and psychic matrices for what it means to be queer and believed they had to be at least in some ways different from the ones that often populated queer studies and popular historiography. Wherever this has taken us, we try to foster a performative critical approach: a balance between promiscuous archiving, historically grounded analysis, poetic hermeneutics, observing the past as it coincides with the present, and at times, resting in critical stillness, letting many possible answers unfold by themselves. If we at first approached this work with somewhat abstract notions, we’ve learned something about it in the process. We hope that what we share here, more than an account of a rich life, is a glimpse of a lifetime of queer knowledge-making and a search for ever-different modes of expressive reflection in America’s smaller cities, in the Rust Belt, away from the limelight.

(Note: While the first interview was collectively prepared by the Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project, Camille Hopkins, a long-term local white trans activist, took up the role of the interviewer. The second interview was conducted by Adrienne Hill and Ana Grujić.)

1950s

Ari Moore was born in the early 1950s, on Buffalo’s East Side, where she remains to this day. Until well into the 1960s, much of the East Side was a lively working class neighborhood, large parts of it historically dominated by Polish immigrants. It is home to the Buffalo Central Terminal, an impressive art-deco edifice which, active from 1929 to 1979, is then deserted, leaving the city that once was an important network of “stops” on The Underground Railroad without an actual, main railway station. By the end of the 1970s, white flight is complete, as is the razing of the neighborhood’s economy and resources, sealed by a network of expressways constructed by this time, obliterating its streets, parks, and severing it from the rest of the city.

Ari reminisces: “The ‘50s were a very interesting time here in Buffalo. It was a time of the nuclear family. A time when work was abundant. The fledgling middle class of Buffalo and its, at that time, fledgling first-ring suburbs were just coming about. And basically enough—there was enough to go around for just about everyone . . . Jobs, work, individual achievements. And Buffalo has been, for the African American community, a long-time bastion of civil rights. We had a thriving Polish, Italian, Irish, German, Black, as well as Hispanic community. Each with its own little enclave, but within that, the GLBT community found its own place to foster, grow, and expand. Right here in Buffalo, which was wonderful.”

Buffalo’s lesbian and gay bar scene was reaching its peak, and one of the venues that is still fondly preserved in local queer memory is the Little Harlem Hotel, run by Ann Montgomery. Michigan Avenue, or the Jazz Corridor on the East Side, where Little Harlem stood, was the home to many a popular music joint. Montgomery’s spot itself had been a stop for a procession of legendary blues and jazz performers since the 1930’s – the time during which it was welcoming to the city’s black, white, and much smaller Latinx and Native American gay and lesbian communities. Less iconic is Winters, which stood on the corner of Michigan and William Street in the 1940s, owned by two black women. Parking lots are in the places of both spots today. Two bars run and patronized by black lesbians “with a few gay men” in the 1950s, were both on Cherry Street, and are mentioned in the oral histories recorded by Madeline Davis and Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy. Remembered by their house numbers, “557” and “217”, their exact locations are practically impossible to determine with certainty, since the street was renumbered and pushed back to give room to the emerging Kensington Expressway. Serendipitously, etched in the stone edge of the freeway, where “217” may have been, the word Sankofa “Go Back and Retrieve It” is etched and its visual symbol of a bird with the head turned backwards and the feet pointing forward. As recorded in Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold, Davis and Lapovsky Kennedy’s ethnography covering the city working class lesbian bar scene and sexuality from 1930s to 60s, many venues frequented by queers and located west of Main Street (a symbolic and geographic border of race and economic segregation) were to a varying degree actively and passively hostile to people of color. On the other hand, queers of all races were more likely to find peace from the police and civilian bashing in the straight bars on the East Side.

Hometown Queers

An interesting aspect of Buffalo’s queer politics, we learned in conversations with Carol Speser, one of the city’s most active and reputable lesbian organizers over a period of several decades, is its social character as a home town. Its queer community’s history is filled with strife, organizing, and parties, but most of its members are from Buffalo and the area. Or, as Davis put it – “You don’t come to Buffalo to be gay.” Coastal theories of LGBTQ identity/community development posit that this development mostly comes from leaving your community of origin and building an identity that is wholly autonomous from your position in your family of origin. Conventional wisdom has it that these hometowns are “behind” big coastal cities in community/identity development. However, hometown queers, Speser insists, actually have a qualitatively different political task than many of their big city counterparts. LGBTQ people in places like Buffalo are trying to be queer and members of their communities of origin. They come to their queer selves and attempt to find life on the same streets where their biological families, unknowing exes, schoolmates, co-workers, and old neighbors still live and work.

Turning the focus to many other Rust Belt, Midwestern or Southern home towns, demands that we rethink our paradigms of queer pleasures, self- and space-making and unavoidably, our concepts of inside and out, as well as the axes of political change.

The character of a home town complicates the conventionally conceived stages of the coming-out narrative as one of appearing from the secrecy of the closet into the light of “one’s true self.” Stone Butch Blues, the ur-text of working class trans and butch/femme literature, which, incidentally, largely takes place in Buffalo, shows the closet to be what Ari Moore describes as a revolving door, in particular for trans people: “I was out and I was in, and I was out, and I was in. And there was a time when there was a literally revolving door. (Laughs.) Sixteen years old, I have a boyfriend that I am seeing on a regular basis every weekend. And then every other weekend, I am pseudo-dating this girl, because you have to remember, the sixties, late sixties, even the idea of being homosexual is frowned upon. And there was not even the term ‘transgender.’ It was ‘transvestite.’ And even at that young age, I knew I was so much more than that, because it wasn’t a fetish for me. As I said, it was an existence that I needed.”

Clip Two: “It Was a Personal Actuation”

Knowing she is more than a high femme gay boy, around eighteen, Ari decides to take her coming out as a woman to another level. Yet in the black queer community at the time, she is considered gay, even if she presents very androgynously. Then she adds, “But there were times when I delved into the depths of butchness” (laughs) “much to the delight of some of my suitors.” With a palpable pleasure, Ari describes her “androgynous period” in the 1970s, while she teaches art at Buffalo’s Albright Knox Gallery: “… at that time, the blowout big Michael Jackson bushes were the rage. And I learned how to straighten my hair, and hot comb my hair, to give me a decent pageboy, which I wore marvelously. And I had a 30-inch waist (sighs) . . . cutoff jeans and little tie dye shirts pulled up around your waist, tightly, showing off your midsection and your abs and your legs, were very, very hot at that time. And for the hippie movement and all the polyester that was floating around, things—if you have a decent body, things cling to you quite well. And cling to others.”

Considering queer politics and social life in the context of a strong identification with the ethos of one’s hometown black community, will extrapolate specific meanings from such a study. Queer identity doesn’t take precedence over being part of the structure of the local black social fabric, as both are indispensable and require negotiations. This will significantly figure in Ari’s personal life narratives, activism, and art. Neglecting to see hometown queers against a more specific cultural background, leads to a set of misconceptions about the relationship of race, small communities, gender and sexuality. To a certain degree, similarly to the South, the Rust Belt is popularly referred to as the repository of the nation’s most retrograde unconscious. This not only silences the narratives of how desire operates in these circumstances, but also invalidates local histories of survival, resistance, and even thriving, and significantly limits our ways of historicizing queer lives in all their complexity. In Sweet Tea, Black Gay Men of the South, E. Patrick Johnson admits that publicly asserting one’s politics and sexual identity is “not the norm” in the South. However, Southern gay subcultures have been rich and long, and black men have sustained and cultivated them by “[drawing] on the performance of ‘southerness’”: the same cultural keys such as “politeness, coded speech, religiosity,” to remain part of the larger black community and Southern culture, but also, to open spaces for queer subcultures. We see how “gay community building and sexual desire emerge simultaneously within and against southern culture”, not a desperate game of mimicry in a war of cultures, but a result of desiring both. A similar attachment to local cultural traditions such as church-going, to historical neighborhoods with their tightly-knit communities and oral histories, and a commitment to familial ties and gatherings has shaped Ari’s personal, political, and artistic choices, at the same time as she shares accounts of having to literally go back into the closet over long stretches of time in order to remain part of this social and cultural fabric.

An example of relying on social networks and resources in one’s own small-city black community in order to make a queer existence, is remarkable in Ari’s story about her coming out to her mother, and negotiating her possibilities with societal and familial interdictions. (Sound of paper rustling as Ari unearths The AMoore Chronicles.) Several years ago, she started chronicling in illustrated form her “trans journey,” beginning with the early 1970s. In here, there’s a picture of this threshold moment: “I came out to my mother at 16, sitting at the end of her bed: ‘Mommy, I feel like a girl.’ She said, ‘Okay, baby.’ Most important damn thing she said: ‘Mommy still loves you. I know a nice psychiatrist who – we’ll make you an appointment, and we’ll see if this is really what you want.’ That—and I tell every single parent of a trans kid—if you say that, I don’t give a damn what anybody else thinks or says about me . . .That is paramount for any trans kid.” Soon Ari informs Ms. Moore that she should save her money, since the “nice psychiatrist” knew less about the problematic than Ari herself: ‘Mommy . . . he’s making his report on me. You should be paying me, not him. I’ll figure it out.’ And [I] went to my father’s general practitioner, and he just gave me that gentle Santa Claus look and said: “Ari, I have no expertise in this, but if I can find someone to help you, I will. I won’t tell your father.” And then another example of how queerness for a long time found its place in small patriarchal and often quite religious communities, and even used its cultural codes to its advantage and sometimes, a good reputation: Ari’s mother, “coming from a world. . . being a debutante,” was well familiar with the company of black gay men. Ari explains: “Gay men were the intellectuals, the fashion plates, the fastidious ones in the group; the well-dressed, well-mannered. And, ‘No, ma’am, you don’t have to worry about your daughter. I will get her home at twelve o’clock, no matter what.’ She was experienced in that.” Still, anticipating the challenges that Ari as a black and trans woman would encounter on her way, she offers to arrange for her to go to college in San Francisco, in the words of Marlon Riggs, ‘that gay Mecca.” Ari declines: ‘No, Ma, I think that I’ll be okay here.’”

Clip Three: The Benefactor

When three decades later Ari loses her mother, and the two family networks, the trans and the socially sanctioned one walk in the room together with their different expectations, the revolving door spins once again: “I was outed to my brother as we buried my mother. That was probably the last time I wore a man’s suit, and I looked like this—the only big dyke in the room. My hair pulled back in this black ponytail. And at that time, I was binding, so I had to wear oversize suit jacket and tie. And different women coming up, patting me on the back, saying, ‘Just let it out, just let it out.’ And I was looking at them, ‘What the hell do you mean? All the crying or lamenting, I did way before this funeral started, and the discomfort that you see is because this damn binder is gagging me.’ Ari’s two trans sisters, Marquita and Donyette, also attended the funeral. They had known each other since their teens: “We had the adventures and the chance to be young, trans, and stupid for all those years. Wearing the sexy clothes, consoling each other when one boyfriend or another quit them. . . So, as we transitioned into adult women, naturally my sisters would be there to support me. They were off to the side, but one of my brother’s friends knows one of them from—I don’t know. ‘You know, them ain’t really women. And we hear that your brother is still wearing dresses.’ So, my brother says, ‘Well, you can’t be around my wife or kids.’ I’m like, ‘Okay, fine, but that’s between you and God, because I’ve already made my peace with God, and God is fine with me.’ Ari continues to send birthday cards, and eventually the children and the sister-in-law demand to see her.

It is impossible to think about race relations shaping queer histories and political and cultural practices, without considering how queers of color, and specifically black, have been denied access to economic and cultural resources, and simply the means to exist safely, let alone thrive. In that regard, the topic of the difference in coming-out trajectories between trans women of color and white trans women, often times comes into our conversations, in Buffalo and elsewhere. Being part of and witnessing these trajectories may have made Ari’s concept of gender identity and what trans is, unmoored and expansive: “Now, mind you, the transgender community is a vast umbrella. And in that, it goes from tip to tip. And some—even at that early time, trans individuals came out so early, because so many trans women of color come out—are identified as sissy boys, or little young fags. I know this isn’t PC, but those were the terms that were used. And their family, and mothers, with: ‘Miss So-and-so, you’d better do something about that boy, because if you keep letting him wear your dresses and everything, he’s going to be out in the street.’ Well, the reality is —those were little trans babies in training. But without the nurturing and the educational and job opportunities at that time. . . they were greatly stunted. Now, on the other hand, all right, for many of our trans sisters and brothers who are white, transition might happen much later into life, after a successful job, marriage, graduation, master’s degree, PhD from whatever university . . . My god, I know trans women who have transitioned later on in life, who were masters of industry! Captains of industry! Unlike the trans [women] of color, [for whom] it’s just been stumbling from one woeful existence to another. At the time, street walking was the only recourse for many. But that’s for another interview.”

By the 1980s, Moore herself is facing the reality of an unsecure livelihood and no means to plan a future. She takes the exam for city government employment, joins the police force in 1984, and stays for twenty-five years (until she has earned a pension): “And that’s literally when I had to go back into a proverbial closet. And my friend that I’ve known since high school became my ‘beard,’ which was lifesaving for me because then anyone having any questions about (gasps and continues in a high pitched befuddled voice) ‘Ooh! Is that person gay? Oh, they have a girlfriend, so they can’t be gay’ . . . So, I got through the first two years of being very deep closeted, and then after that—after I got probation, basically—I said, ‘Well, I can’t help it any longer. They can kiss my ass. I’m putting my, like, gigs back on. I’m going to the club.’ So, I . . . tried to pick up where I left off.”

She doesn’t remember serious issues most of her time with the force, “until the last five years, when it became increasingly difficult for me to pass as a man (laughs). And by that time—which I only found out later from other officers — ‘Oh, we kind of knew about you anyway.’” Already retired, Ari once attends a funeral of a male coworker with whom she grew up. “And I couldn’t—I could not deny going to attend his homegoing. So, I put my best little black dress on, heels, black sunglasses—my designer look—and sat in the back row, and sent the card by the usher to the family up front, and sat there quietly, meditating and paying respects. And at the end of the service, letting everyone, the whole church, out. Got up to leave, and someone yelled, ‘Ari! You can’t sneak out of here!’ And I was like, ‘Oh, God, here it comes.’ And much to my surprise, it was not negative, but caring. ‘Are you okay? Look at you! You look good! Wow!’ And then, from so many of them: ‘Are you really happy?’ And I was like (laughs), ‘I’m happier and more satisfied than I’ve ever been in my life.’ ‘Well, that’s all we wanted to hear. And if anybody gives you any shit or trouble, just let us know.’ I have to tell you, I went out to my car, and I cried more than when I was in church. And I’m not a weepy queen, mind you. And I don’t have many illusions. I know there are people out there that would rather see me in the ground, face down. But for those that gave me acceptance—and, as I’m finding out, still give me acceptance—I at times wonder: What was the fear, or the reservation, that I had at that time?”

The AMoore Project

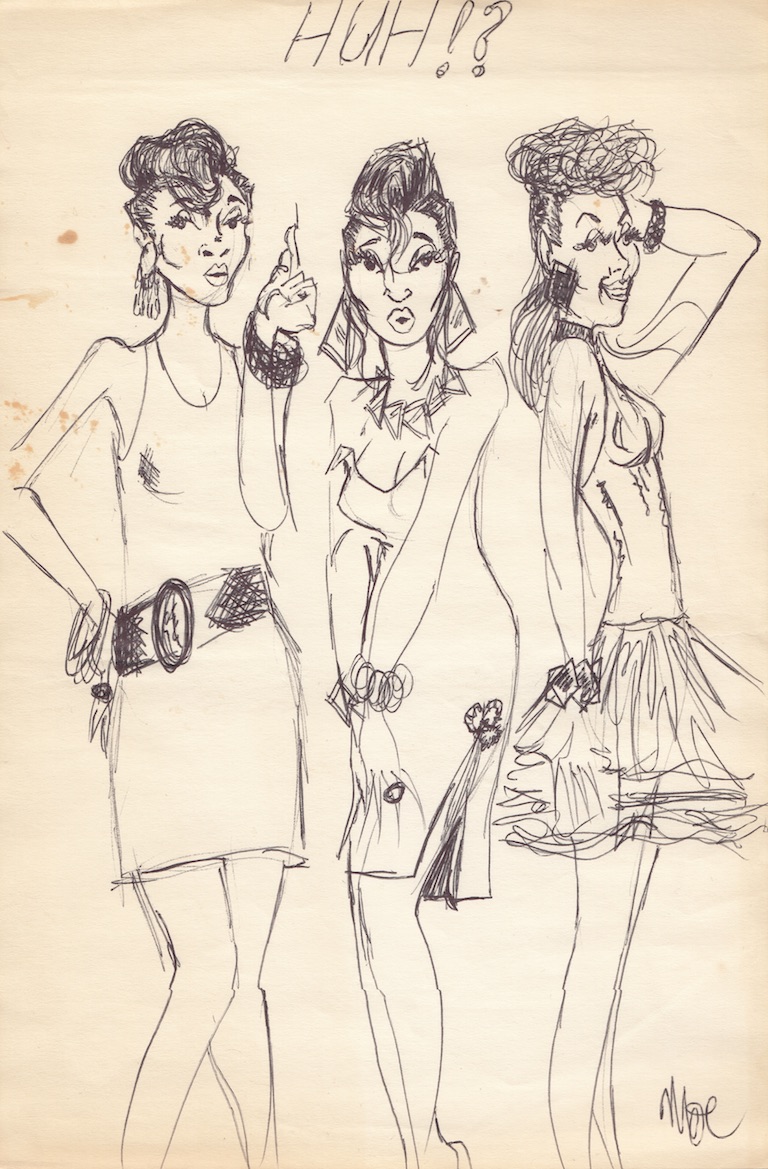

The AMoore Chronicles is only part of The AMoore Project, an illustrated, painted, narrated, fictionalized, performed and multimedially documented universe in which Moore has walked – from the acrylic paint series Queens I Have Known, Couples I Have Known, to Differentiation, a watercolor four-part sequence about embodiment and gender, to oral histories about local lives and activism, to an extensive photo archive with different queens and other trans and differently queer performers from the region, going back to the mid-1960s. Perhaps central in this universe are the expressive tools, narrative patterns, and the characterization of comic book art. Since childhood, Ari has been an avid collector of comic book series. She recounts how her Detective Comics from 1934-58, including the original Spider-Man Issue 1, disappeared in the flames of a wood burner as her father tried to keep the basement warm: “I had a fit. Lucky enough, I saved most of my other collections which I kept in close to pristine condition . . .” Superhero detective comics, she explains, played decisive role in the articulation of her visual and conceptual paradigms.

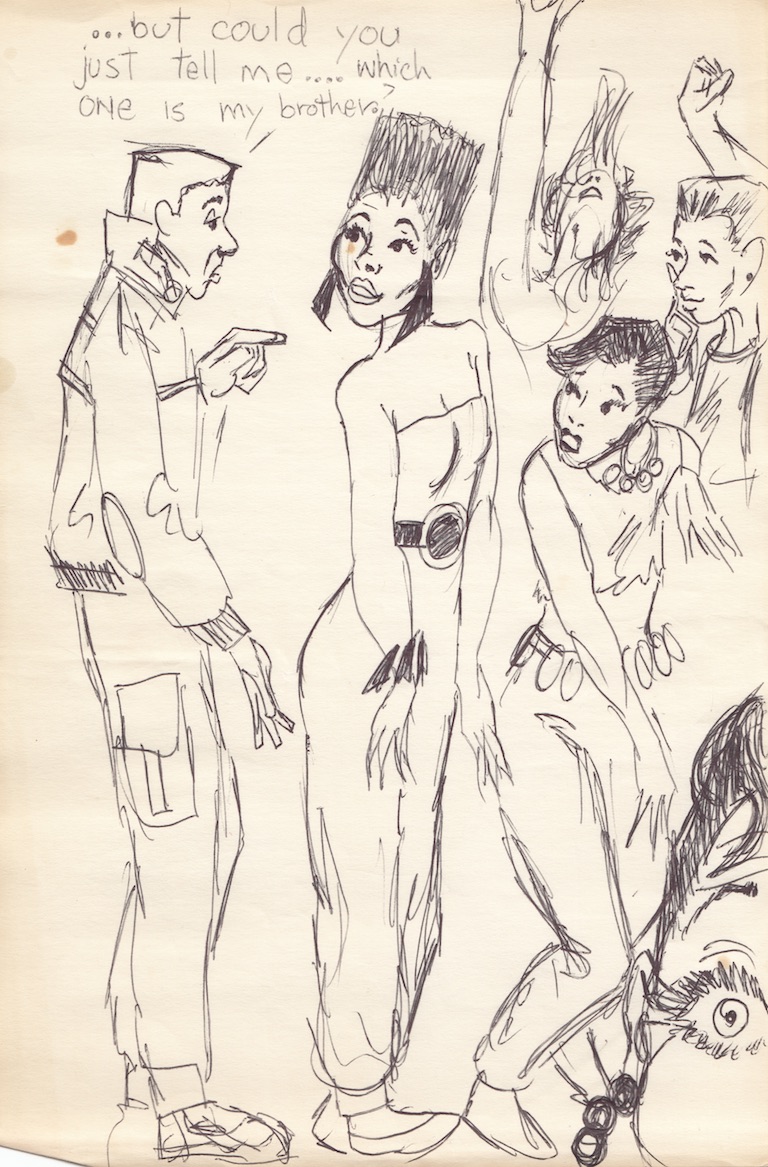

Comic art seems to be the space that allowed Ari to develop her ideas and think through visual identities of trans women she knew and she imagined. When she talks about Spider-Man, The Fantastic Four, Batman, Superman, The Green Lantern, or Wonder Woman, we ask her to explain how the glaring ethnic and gender restrictions in the superhero universe still provided the room she needed for her fantasies and her intimate world: “There were no black folk there. And if you did have female heroes, they were so basic. In the Fantastic Four, you had Sue Storm, but she was part of the male group. Wonder Woman, for the longest, was the one stand-alone female character that stood the test of time. And it’s interesting that her creator was a bit of a fetishist…” But Ari is a visionary – she populates normatively established universes with devious presences, or even subtly reveals that the latter have held their place here perennially. The sexual and queer underground frequently provided unnamed role models for superheroes whose freakish powers are rendered palatable as their sexuality and ethnicity are made hopelessly normative: “Back in 1970, there was no such word as transgender. There was transvestite and transsexuals. The operative short term for that was TV. So at that time, I was doing TV Tunes. This was a short panel of cartoons. I drew them while I was at church, to amuse myself during the pastor’s sermon.” The story in TV Tunes revolves around two black trans sex workers and “their mishaps and unfortunate and fortunate encounters: making a lot of money in one night, going to the bar, getting into a fight with a lesbian, and losing it all. And going home, wigless, shoes broken, and clothes torn. . . The story always winds back in the same corner bar. That’s where everyone in the neighbourhood congregates: the hookers, the pimps, dealers…”

Emory Queen is another trans character Moore created and used to think through “some of my own stuff.” She appears only in four episodes. Emory is a newspaper reporter whom Ari depicts as a “swishy guy who gets very salacious information on some important city local figures.” It is the late 70s and early 80s, and Emory is presenting as male. When a hitman is sent out, the editor asks her to kill the story, but Emory declines and declares: “It’s the truth, and the truth shall make you free! (a pause and conspiratorial laughter, hinting that the moment has a peculiar resonance for Ari.) While the ongoing chase is after “this little gay guy,” Emory reverts to her female self. On the run and out of town, “she has to navigate a series of trans, lesbian, gay, queer and other characters, . . . drives part time across the country. . . while the dogged hitman is after her and her whole crew. The ending is quite brutal, but she survives.”

The ways in which Ari the artist intertwines with the activist, and how Ari the oral historian, story-teller, and archivist shapes the work of the former two, are many. Part of it is the realization that every so often, her accounts of events change, possibly, as multiple historical perspectives accrue in her individual consciousness into larger narrative trajectories – for example, long periods of time are condensed in what appears to be not more than a couple of years. In the 1990s, Ari started getting politically involved, and a little later, together with twelve other trans women of color founded the group African American Queens – as she recounts, in response to the death of one of Buffalo’s queens, Miss Cougar: “We vowed that we would forge together to form a—at least a phone tree, a loose-knit group to keep track of each other. Cougar was a sex worker who was murdered, and the body was cast on the 190 Southbound, next to the bridge to the Unity Island. Her murderer was never found. And even though many of us continue to try to put the pieces together, it was just—too much time had gone by.” When she claims that African American Queens were a response to the murder of Ms. Cougar, but later we realize that the two events are separated by more than twenty years, we begin to lean to understand Ari’s narration in a less linear and more of a cumulatively synchronic way. All these facets together form The AMoore Project.

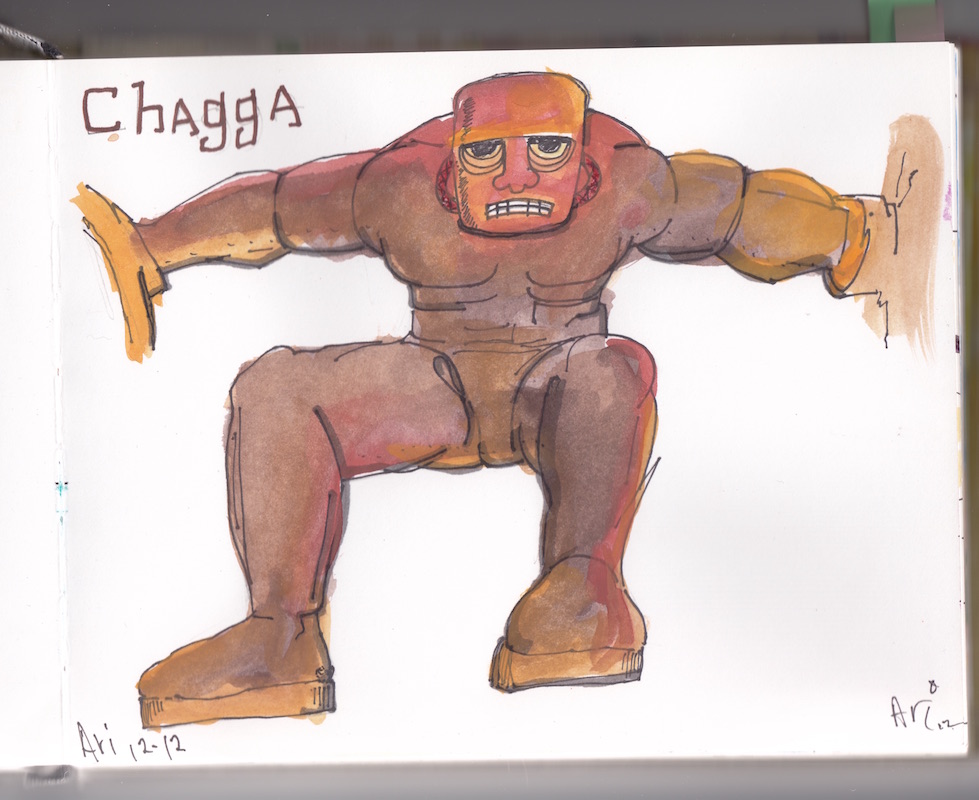

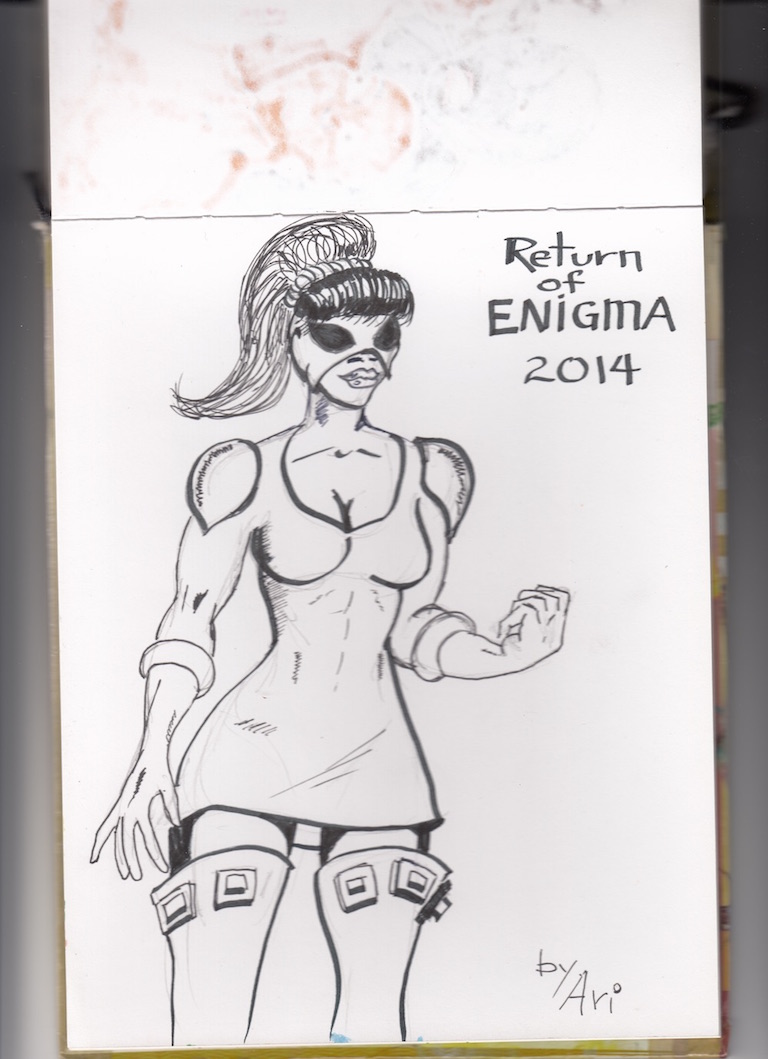

The name of The Enigma, yet another comic series, echoes cis people’s gawking curiosity about trans people (“Oh, you started like a woman and now you are a man?! Or is it kind of both?”) In it, Ari explores the powers and special abilities of trans characters that could be employed in the service of an extremely vulnerable community: “Enigma’s abilities are not over the top, superhero stuff, not like radioactive spiders… you have a woman that still has the agility and the physical powers of let’s say a … football player. How does that work into crime fighting or avenging the transgender community where so many of us are murdered, mutilated and defiled?” She explains that the needs of trans women of color are quite different to those of their white counterparts: “Access to education, jobs, medical [care] and information is woefully lacking for trans women of color. Many times, trans women of color have no other choice but sex work. Even for, at that time, those with education.” The acrylic series Queens I Have Known comes to mind again, as a documentarian project in which though art Ari resists communal and institutional neglect of this extreme vulnerability.

It is, however, the sketches for another graphic novel, for a long time in the making, that left us breathless. Mahogany is a striking example of Ari’s need to zoom out historically and geographically and reflect on embodiment, language, and the entangled regimes of gendering and racialization, on a broader philosophical level. It prompted the second interview. We ask her to tell us the story of Mahogany’s history: to comment on its Afrofuturist aesthetic, narrative structure, and a typical preoccupation with the fluidity of body and gender, the non-linearity of time, the future of race and humanity, answers to these persistent questions given by a non-human intelligence that precedes human consciousness. We are struck by its theoretical resemblances with Octavia Butler’s Dawn and quite surprised to hear that Ari is not familiar with her work. We are impressed with the synchronicity of unacquainted minds.

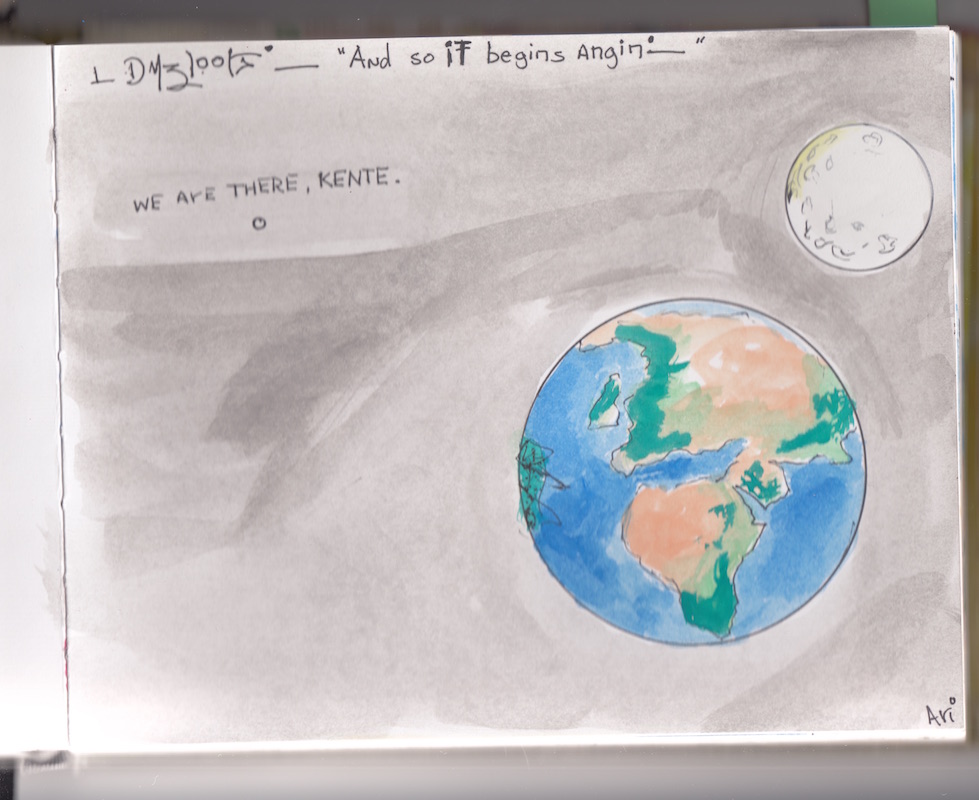

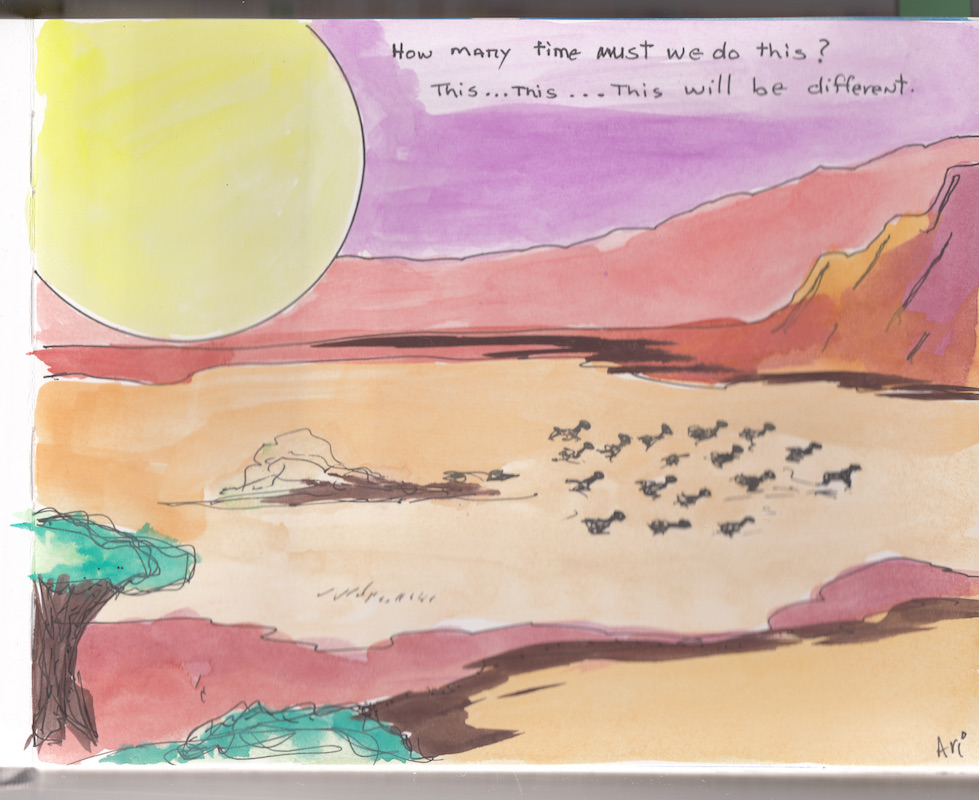

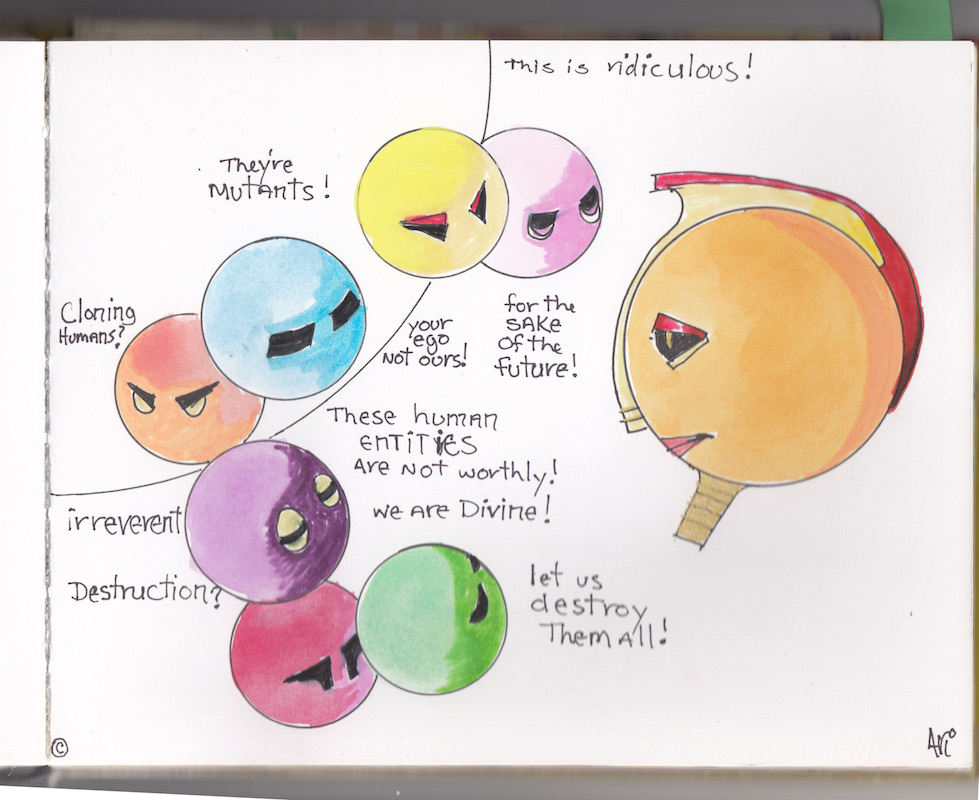

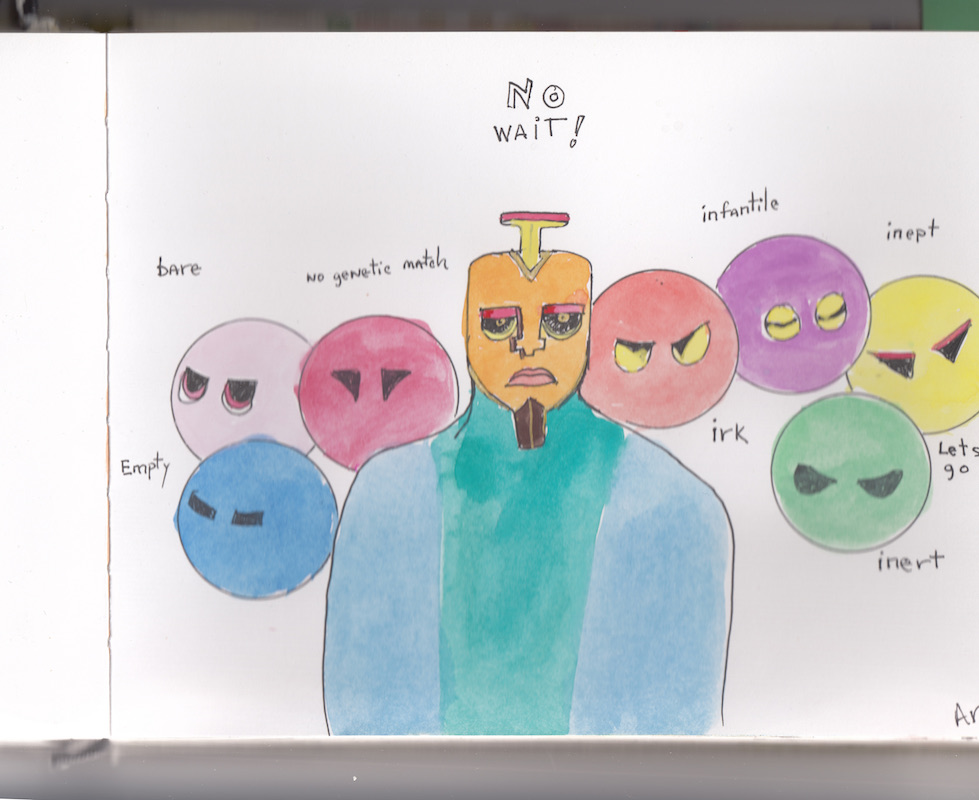

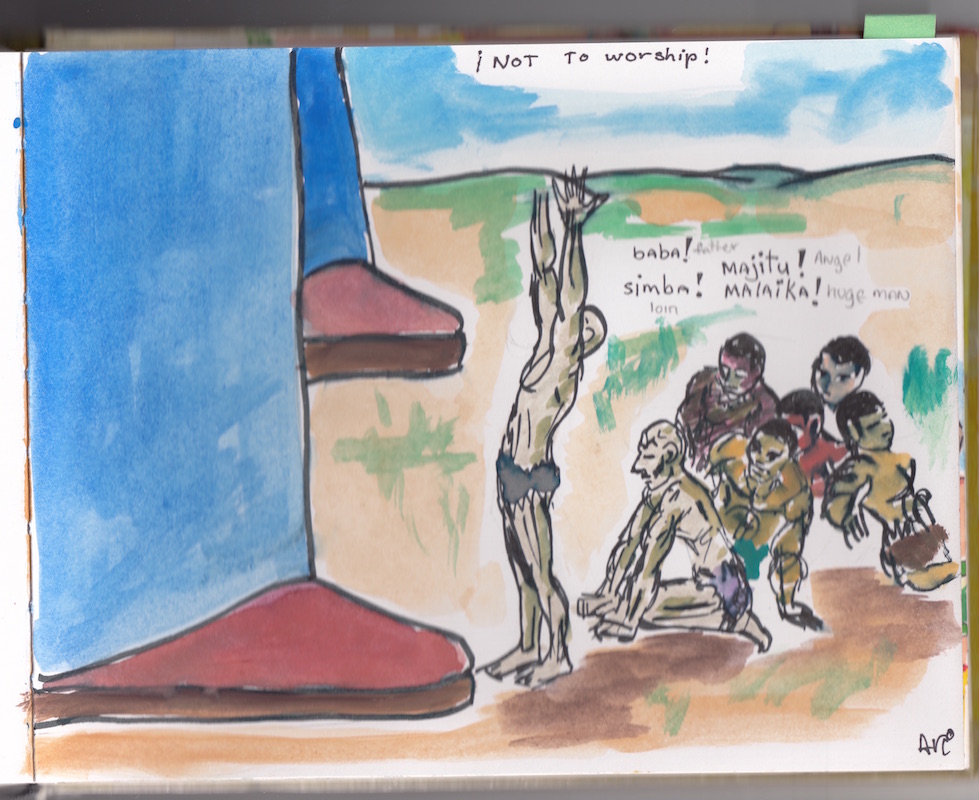

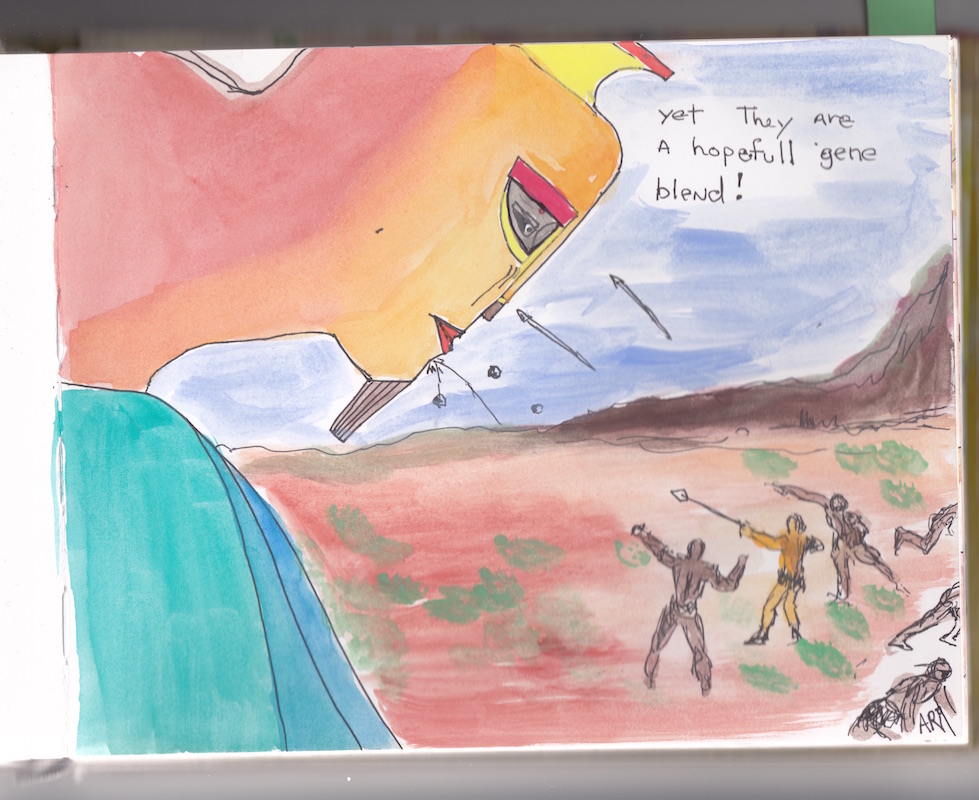

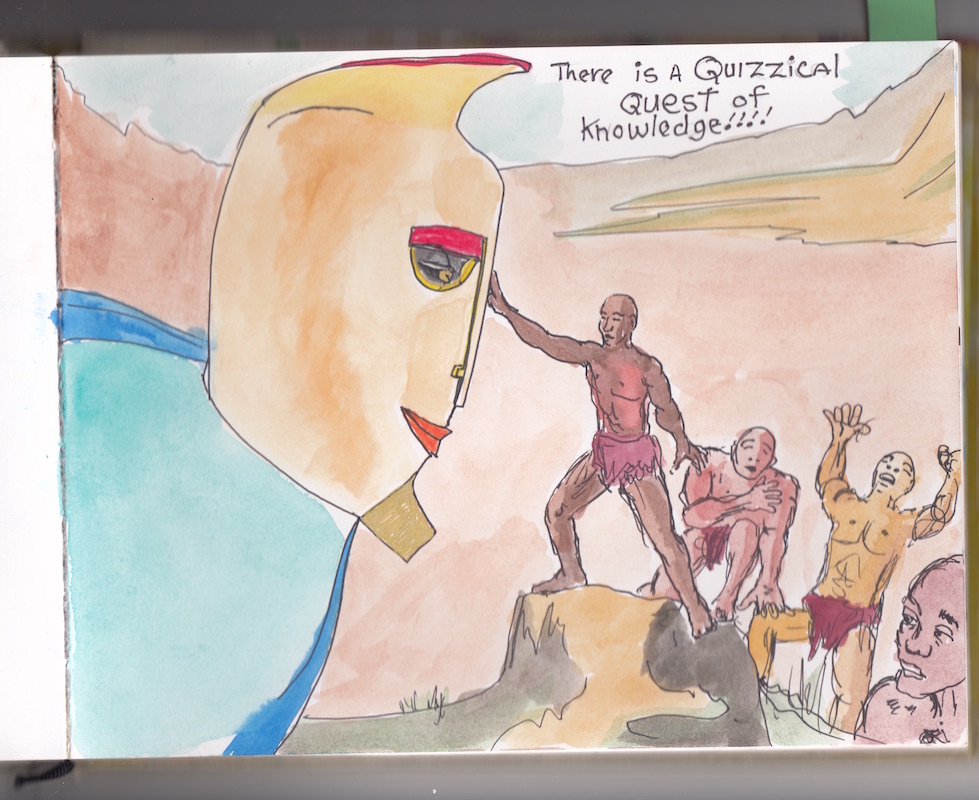

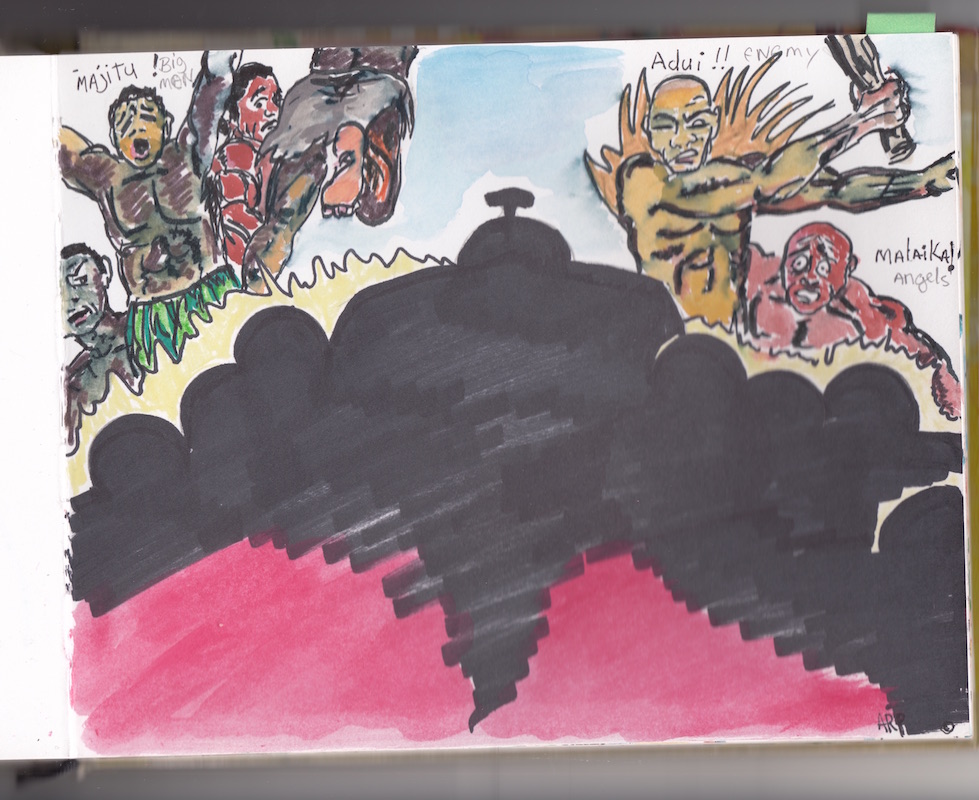

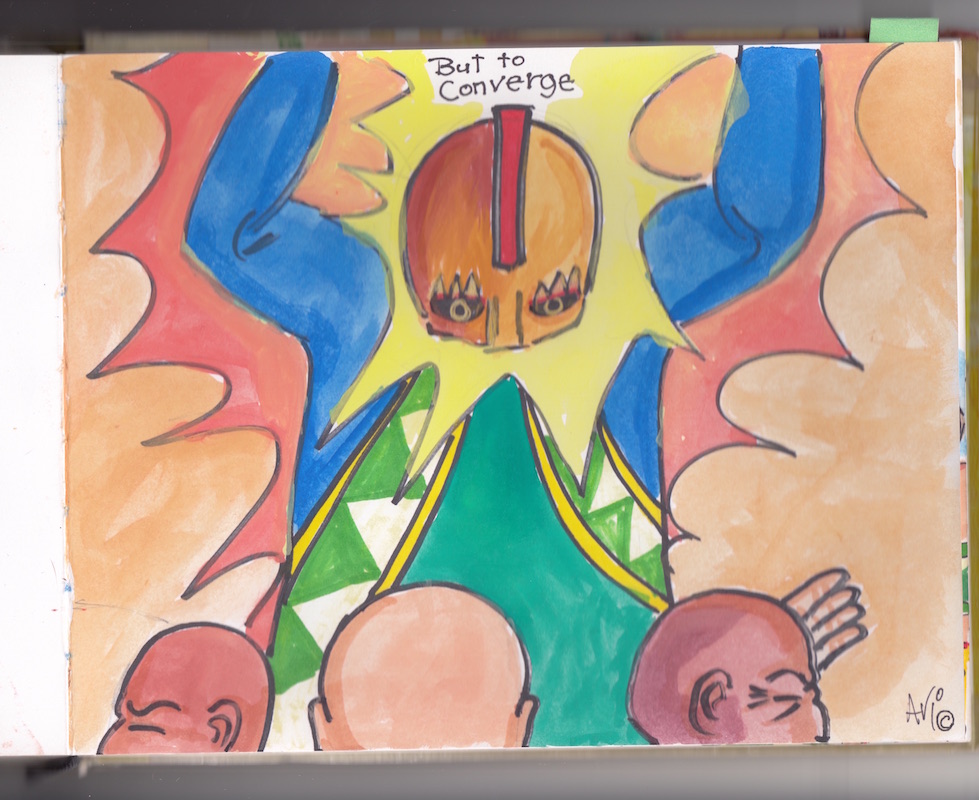

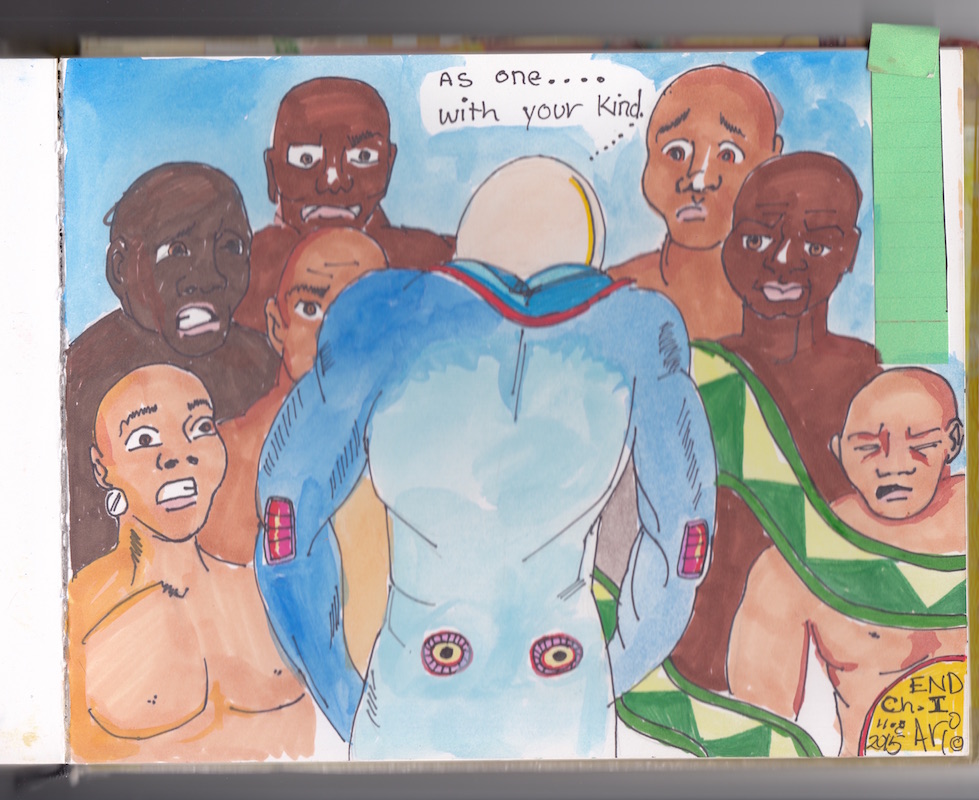

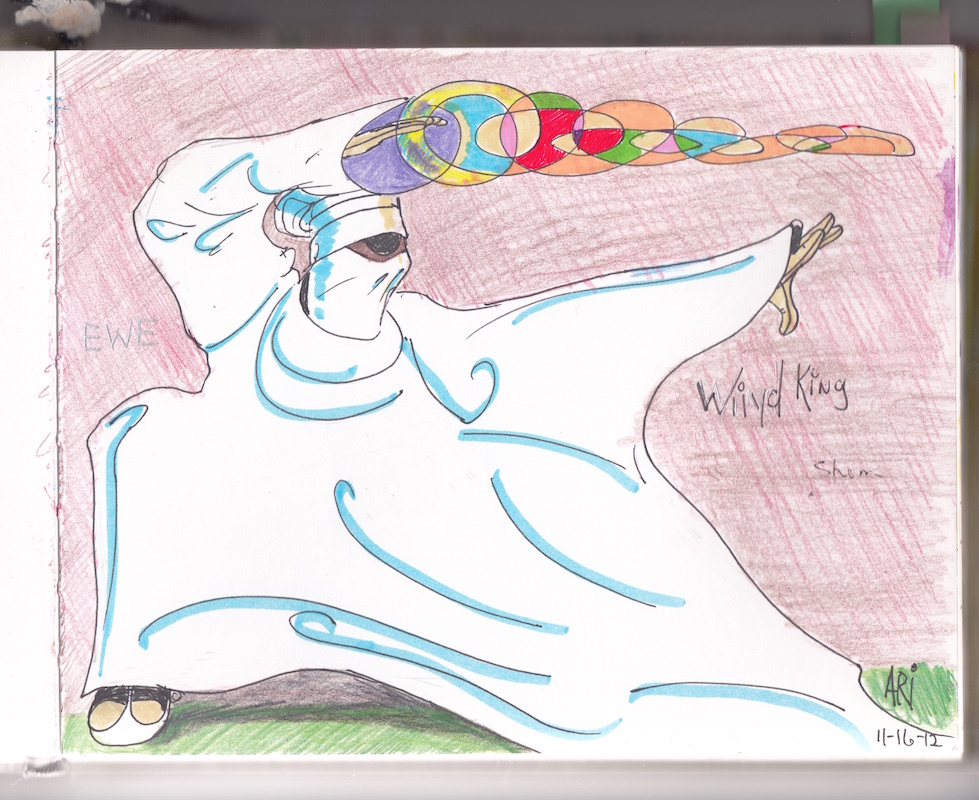

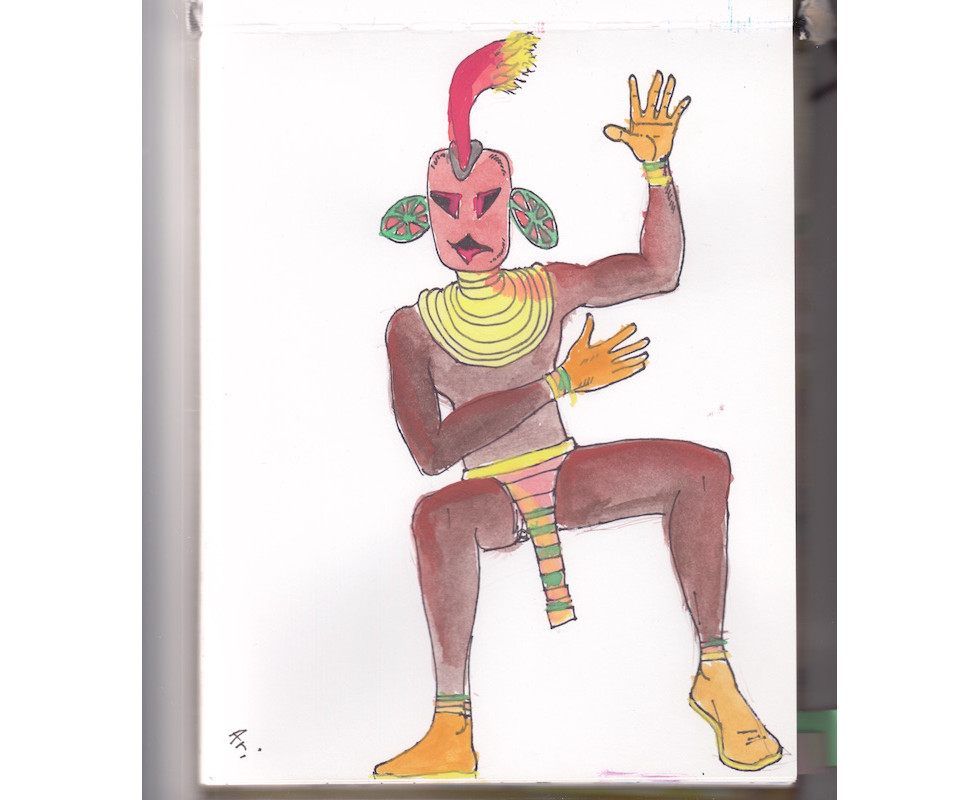

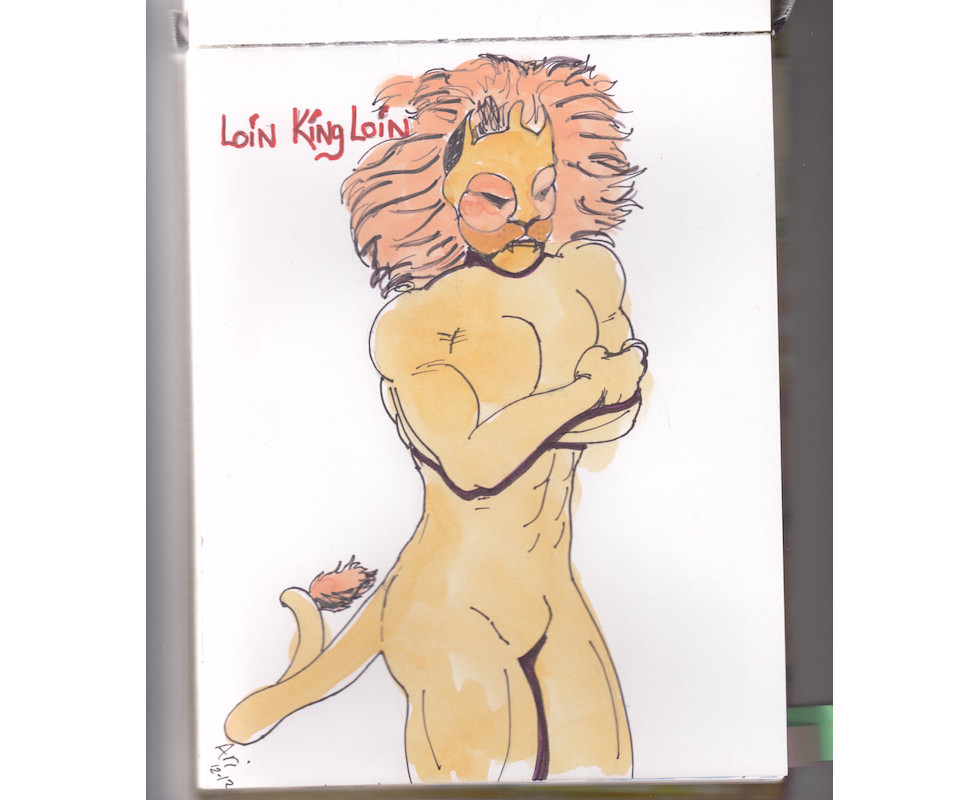

Slideshow: Sketches for the first book of Mahogany, Ari Moore’s graphic novel, together with the individual images of the alien deities from the story. Moore derived their names from Swahili. Since our conversations, Moore has completed the entire second book and is still working on the third book. While the original idea was created in the 1970s, Moore resumed serious work on the series in 2012.

[Opens the notebook with the sketches for Mahogany and reads the epigraph on the front page]

“…The AMoore production, a research of old African gods, a Shakespeare-like story, space age style … ancient gods entangled with ancient aliens on earth. A monarchy, a matriarch, and Ebony Mahogany, with the villain the Albino…” (At the time of the conversation Mahogany was in progress. As of January 2018, it is almost finished.) Among other themes, Mahogany is about calling attention to the African origins of human civilization and imagining first contact with the deity. Ari follows on the waves of radical reimaginings of the Black Atlantic as a corridor for the diaspora’s spiritual and cultural ties to the African continent, and uses Afrofuturist tropes to envision the liberatory potential of these connections. She recounts the stages of its production: “The original concept was formed in 1975, as I daydreamed in one of my classes of the form of the five original deities that were going to be [involved]. The concept of the Mahogany, the Albino, and the tribe that the Mahogany aliens become antagonized with were brought in as the story continued. The Albino doesn’t want to allow these foreigners to mix with the tribe. The ironic part is that he is an Albino in Africa. The connection between ancient aliens and gods was [added] in the 2012 version [when work on Mahogany resumes] and the setting of the ancient Africa… the concept of . . . being able to have a close interaction with deities, as much as Ancient Greeks a lot later thought they had a direct relationship with their deities.”

Along these extensive historical trajectories, Ari is interested in the shifts in the notions of gender: “We are left the spoils of that . . . mother of civilizations… Interesting enough, globally, a shift happens later from the mother of civilizations to male dominated societies, separating the female from the male over historical time. So very often we are seeing the narrative, at least in comic books and graphic novels, from the point of view of an Anglo-European male. Or from this point of view, we imagine what could be if, or what will be . . . I want to experiment with these themes in the story of Mahogany. If there were such aliens, how would they perceive the first society of humans on a continent? On the opening pages, you will see them wondering: ‘How many times do we have to come to this dingy little planet? This little ball of mud and water on the edge of the universe, when there are much more advanced places we could be?” (Responds in another tone of the voice): “No wait, there is something here that has potentials like nothing else that we’ve seen . . .” One of the question raised in Mahogany is the historical pattern of always starting societies anew, of throwing old knowledge on the side. The gods are angry: ‘How many times do we have to recycle this dust bin? They haven’t evolved any farther than the last time. They are still killing each other with rocks and stones.’ . . . Ari explains: “But it’s this not giving up, this doggedness of continuing to work or observe something until you find out it’s not for disposal and as a matter of fact, that there’s something beautiful there…All we have to do is . . . be small. That’s one of the primary concepts to Mahogany.”

As the conversation continues into the night, Ari ruminates on the concepts of language, consciousness, and the divine in Mahogany: “There’s a line that starts it out… and you won’t even really take note of it… written in the original alien language, which of course is undecipherable to us. So, on the top of the story line, I have to conceptualize an alien language. And how does the human tongue… pronounce that? (Laughs). If aliens don’t have, as we perceive it, a physical body… (Silence, then whispers excitedly) . . . how would they communicate? What would they look like? … Of course, even when we talk about god, as a deity, we imprint our own stuff, excuse the expression, put our own shit onto the person of god. God is not male, god is not female. We all admit, at least basically to the concept that god is a spiritual being, and she . . . has no body . . . So, in the first pages of The Mahogany, you see where in the first phrases of the alien language they are weighing over the human imprints on deities . . . Human impatience. The contempt. And then one of the deities says, ‘Let’s just kill them all. They are not worth it.’ And there is another who sees in our religion love, respect and compassion. But even if they are aliens, would they be separate individual entities, even without physical forms would they have opinions?”

However, at the time we are discussing Mahogany, another graphic novel, 1920, is preoccupying Ari. Geographically quite intimate, in terms of its temporality, this one is clearly marked by the fluidity typical of some classical science-fiction texts, where characters travel back and forth in time in order to understand the historical and social composite of race and gender. She confides: “It’s on the drawing board as I speak. I am back visiting the boys in 1920.” A black, a Polish, a Latino, an Italian, and an Irish boy from Buffalo go back in time – from 2019 to 1920. “Because, [this] one specifically deals with the ethics of race in the1920s. It’s five different ethnic groups in that story. They are all forced to intermingle and deal with the issue of race and ethnicity at that time, coming from this moment . . . So where does that fit in?” (A groan) Several months later, she shows us large, colored image panels. In the summer, when we run into each other at an art show opening, she tells us about an offer to make 1920 into a feature film, and asks me to play Nikola Tesla.

Activism, a Dialogue

A friendship with another local trans woman, Camille Hopkins, brings Ari to political activism to which she has remained committed ever since. They co-founded Spectrum, the first trans support group for Western New York, and later, Ari started the African American Queens.

Camille: What were your experiences as a trans activist in Western New York, and at the state level? When did you start coming out, or moving in that direction?

Ari: (Laughs.) Well, you were right—I was right there with you when so many of those situations occurred. When Buffalo City Hall did its proclamation for transgender inclusion, I was there when the Common Council did the vote.

Camille: Right, in 2002. September, I believe.

Ari: Right, right. You curmudgeoned me to ride with you on that long ride up to Albany.

Camille: Oh, yes, the following year. After they had passed SONDA, the Sexual Orientation Non-Discrimination Act, and purposely left out the part that would have given transgender people protections. So, yes, it’s a long ride to Albany.

Ari: Yes. And continues to be a long ride. We were just up there last year, and it was done without the influence or prodding of ESPA (The Empire State Pride Agenda), since they have closed their doors, saying that Mission Accomplished much as George Bush has said (laughs) [Ari refers to the legalization of so-called same sex marriage in New York state, which took place in 2011]. The trans community has stepped up in New York State to show that we might have an executive order from the governor for transgender rights, but it cannot stop there until we actually have the actual law for GENDA—the Gender Expression Non-Discrimination Act—on the law books.

(The laws in the city were passed, but as Camille repeatedly points out, there are no mechanisms for enforcing them. GENDA, the statewide bill that would outlaw discrimination on the basis of gender identity, was finally passed in the State Senate in January of 2019.)

Adrienne: I remember—I was actually talking to Camille the other day. She told me about coming with you to Albany for the first time. If I recall correctly, Camille, you said that Ari didn’t want to talk at all. And I wanted to ask Ari, a) do you remember that story the same way, and b) if that’s true, how did you find your voice, and start feeling like you could talk?

Ari: Anything—any of you little babies shall realize that when you’re new to something, and you first walk in a room, you observe. You watch, and you see intensely, and you study who’s who, who’s the actual power maker, who’s the buffoon, who’s the person that makes the decisions, and who’s the leech. So, after quickly making those observations, and having a past as a—my past as being an educator; my past as being in law enforcement; my past as being a queen, because any good queen that is worth her sequins and rhinestones will tell you that our community is very sensitive to people when they give us a long shit of doodoo, and tell you it’s peppermint candy… yeah, it did not take long for me to start speaking up.

Camille: Well, and you continue to this day, especially regarding the Buffalo Public Schools trying to develop a transgender student policy. You were quoted in the newspaper, in fact, I believe a few weeks ago.

Camille: Yes, thank you for being there. And I have to tell you, you have so much more patience than me, because you were talking to people who were showing outward hostility towards trans people. And I love that about you.

Ari: . . .Yeah, it’s true, but also, I realize that it’s important for a person such as me to be in the room, many times. As I—when we were done in Albany that one time, with Melissa Sklarz and Joan, and I told them: “This cannot be a movement that’s just making decisions by a bunch of old, white broads. Everyone has to be on deck for this to succeed.” So, many times, my dear friend (scoffs), I have to get on my big, Black, transgender horse, and ride into the fray, time and time again. Because it’s necessary for people to see that there’s a whole spectrum of transgender people in this struggle for human rights. And I try to instill that with others in the community: that we have to start supporting those that support us. We have to support—just as back in the day, when the Stonewall riots occurred, there were a lot of cisgen people there, throwing bricks and Molotov cocktails right along with the queens. And the same issue has to start being actuated now. We have to support every single rights group: Black Lives Matter, Native American lives matter, Latino lives matter. I don’t want to say all lives matter, but you get the gist. If you come to mine, I’ll come to yours.

Clip 4: “The Privilege of Passing”

Bibliography

Cvetkovich, Ann. An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Culture. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006.

Hill, Adrienne C. “Archives: Trans Trailblazer.” The Loop, Issue 68, page 4 (June 2017). www.dailypublic.com/sites/default/files/attachments/2017/Jun/Loop12pagesMAY31.pdf

Johnson, E. Patrick. “Black Performance Studies: Genealogies, Politics, Futures.” In The Sage Handbook of Performance Studies, edited by D. Soyini Madison and Judith Hamera, 446-463. Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2006.

---. Sweet Tea: Black Gay Men of the South – An Oral History. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

Lapovsky Kennedy, Elizabeth and Madeline D. Davis. Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold: The History of a Lesbian Community. New York: Penguin Books, 1993.

McRuer, Robert. “A Visitation of Difference: Randall Kenan and Black Queer Theory.” Critical Essays: Gay and Lesbian Writers of Color, edited by Emmanuel S. Nelson. Harrington Park Press, 1993.

Moore, Ari. The Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project - Oral Trans History Series. By the Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project. October, 2016.

---. “Interview.” The Buffalo-Niagara LGBTQ History Project - Oral Trans History Series. By Adrienne C. Hill and Ana Grujić. February, 2017.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York: New York University Press, 2009.

Marshal, David, dir. Swimming with Lesbians. 2009; New York, NY: Blue Sky Project, 2009. DVD.

Vazquez, Alexandra T. Listening in Detail: Performances of Cuban Music. Durham: Duke University Press, 2013.

Notes

- The scarce material that pertains to the local POC queer history are two folders about the African American Women’s group Shades which existed in the 1990s and early 2000s, and a small archive about the Buffalo branch of the MOCHA (The Man of Color Health Awareness) Project, founded in 1996.

- More on Peggie Ames on page 4: dailypublic.com/sites/default/files/attachments/2017/Jun/Loop12pagesMAY31.pdf

- Not only our conversations with Ari, but our whole history project is motivated by the concern with how queer histories are commonly narrativized and made available. Cultural texts, from pop culture to scholarship, which either emphasize or imply how much harder or even impossible it is to be queer outside of big cultural hubs such as San Francisco or New York City, still largely seem to overshadow good and not simplistic analysis of what it has meant to choose not to migrate to one of these supposedly queer Meccas. Certainly, trans and queer people who grow up in big cities have struggled with a host of difficulties, from poverty to all sorts of violence, to the lack of access to health services, employment, and housing, as they have in smaller cities and towns. Yet it is generally more difficult to find narratives (in historiography, film, literature, pop music, or critical theory) that attempt to understand, or honor the choices of trans folks who invest their whole life in as this is popularly perceived, “less cool” or “boring” cities. At this point, as we should, we are able to access a valuable material on lives and work of Ms. Major Griffin-Gracy, Marsha P. Johnson, or Sylvia Rivera, while the same cannot be said about long-term trans activists and trans pioneers of color in less iconicized places.

- Vazquez, Alexandra T, Listening in Detail: Performances of Cuban Music. (Durham: Duke University Press), 2013.

- Lapovsky Kennedy, Elizabeth and Madeline D. Davis. Boots of Leather, slippers of Gold: The History of a Lesbian Community (New York: Penguin Books), 1993.

- Swimming with Lesbians, directed by David Marshall. (2009; New York, NY: Blue Sky Project, 2009), DVD.

- Robert McRuer cites Henry Louis Gates Jr.’s affirmative response to A Visitation of Spirits, a black gay Southern novel, which Gates concludes with hopes that in his next novel, Randall Kenan will “take [the teenage queer character] Horace to the big city…” McRuer acknowledges that having a renowned black but not queer scholar speak about a gay black novel is in itself remarkable, but maps Gates’ observation as “symptomatic of a regional elision in queer theory generally.” He is, he declares, more interested to find out “what (perhaps more radical) cultural work can be done in this ‘somewhere’ that Horace is supposed to leave in order to be somewhat prescriptively queer, 222. Obviously, narratives about relationships to the community of origin could have been somewhat different for queers born in big cities. The subject matter here is however the place of smaller cities and towns in dominant queer historical narratives as early stages of development that need to be overcome for one to be in the life, to use this popular phrase from the past.

- Johnson, E. Patrick, Sweet Tea: Black Gay Men of the South – An Oral History. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 2.

- Ibid., 3.

- This may be one of the factors that while she is well connected and politically broadly involved both in the region of Western New York, and on the state level, the majority of Ari’s close social circle, other than trans women, are also cis black gay men. She is the only woman member of Black Men Talking, Buffalo social group for black gay men spanning generations. Overall, socially, possibly for reasons that Ari offers, the relationships of black trans women, cis gay men and those who are gender fluid, seem to be quite close (black lesbians are present, but it seems in lower numbers). From affectionate mentorship, to long-lasting friendships, when there is an age and life experience difference, these relationships often take the form of familiar structures. For example, several younger black gay men, black trans women (formerly identified as gay men), or gender queer youth that in these social space still refers to themselves as gay, refer to Robert Hairston as “my dad.”

- ESPA was an advocacy group for LGBT rights in the State of New York. Once Governor Andrew Cuomo passed an executive order for the protection of rights of transgender people, ESPA immediately dissolved suggesting that its mission was completed. This decision is often considered to be the sign of ESPA’s lack of genuine interest in trans rights and lives, and a clear indicator of its ultimate goal being the same-sex agenda.

Cite this Essay

Grujić, Ana and Adrienne Hill. “Hometown Queens and Superheroes: Ari Moore’s Queer History of Buffalo.” Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge, no. 35, 2019, doi:10.20415/rhiz/035.e03