Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge

Staging (Within) Violence:

A Conversation with Frank Wilderson and Jaye Austin Williams

PDF

PDF

Frank Wilderson: I thought we might begin by you talking about your work, and how it has come to be what it is today.

Jaye Austin Williams: Well... my "crazy" decision to pursue graduate study was inspired by a recognition that "the theatre", as an industry, was, for the most part, not in conversation with theoretical and philosophical discourses examining anti-blackness, in particular. As a black, queer, partially disabled participant in the industry, I had an "ensemble of questions" (to borrow your wonderful phrase) that were not being addressed—at least, not directly—about the overt and covert aggressions black people consistently confront in attempting to live in the world. And so, I am delighted to be asked to take part in this special issue of Rhizomes, because I'm piqued by the popular presumption that theatre is not engaged in theoretical and political contemplation. And I have to say, I think that continues to be the case to a large extent. So I am intervening in this neglect, through projects like the three productions I directed at UC Irvine: The Colored Museum, The Trial of Dedan Kimathi, and The Liquid Plain, and with the writings that have resulted from them. My aim in framing this triumvirate of plays the way I did was to bring UC Irvine's Drama Department into a conversation that, in my view, it was loath to have, because such a conversation foregrounds anti-black racism as a very particular, deeply-rooted and far-reaching animus. What I mean is, it's not enough to focus on "diversity" or to talk about racial hatred and discrimination in their broader contexts. Rather, it's about how anti-blackness constitutes a structured antagonism that manifests overtly and insidiously, and in turn, impacts everything else—not least, the psychic and physical lives of black people all over the world. The extraordinary constellation of scholars, to whom you helped expose me, has been intervening across the last forty years and beyond. And some of those scholars had to pursue that work completely on their own, without any kind of structural or intellectual support, trying to diagnose what underlies the onslaught of this antagonism that so many refuse to discuss openly.

My larger project leans more toward the Humanities, within which the field of Black Studies resides, than toward the Arts writ large. In other words, I focus on the literature of black dramatists and its transliteration into theatrical performance in order to foreground a conversation they have, in fact, been having with audiences for some time, even under the press of having to "entertain" for reasons beyond their own enjoyment, interest or highest good. Some contemporary dramatists are consciously confronting the black predicament; others, more subconsciously. But in one way or another, many black playwrights engage the black suffering borne of captivity—what Orlando Patterson describes, in part, as "general dishonor"—in their work. I read these engagements as dramatic theorization, and I am committed to remaining on this path, no matter how fraught. And it is fraught indeed!

FW: You've done a great job. And it's a job that is hard to do anywhere you go. Having worked with you twice (once as your dramaturge—for your production of The Colored Museum, and then again, as the faculty mentor for your dramaturge—the talented Wind Dell Woods—on The Liquid Plain), and having seen you do all this great work over the years, I came to understand how the dynamics of this difficulty for a black intellectual/artist are structurally the same as those faced in the Humanities by a black intellectual/academic. However, there seems to be an added layer of intensity faced by the black artist in Drama and Theatre that is even worse than it is in the Humanities. What I mean is, in the latter, everybody reads; which is to say, people are used to being called upon to explain their perspectives; and as a result, you can demand that the conversation take place at a level of abstraction where people actually have to put forth an analysis.

FW: Not to be too stereotypic, but it seems that in the Arts (at least in the U.S. and especially in Southern California) nobody reads.

JW: Listen, I may be generalizing a bit, too, but there do appear to be a good many theatre practitioners who see the kind of close reading and analysis we do as somehow anathema to "true" art.

FW: Artists often talk about race and power by not really talking about it; certainly not feeling a need to explain what they say. One finds them batting around anecdotes and feelings and empirical observations (a) as though the meaning is transparent and (b) as though their meanings are significant to and shared by black folks. There's no need for analysis when a singular kind of white/multicultural affect is running everything—standing in for a critique of power relations. To actually stop and understand it would be anathema to the "good feeling" of the arts community on campus, and in the U.S. more broadly. But let a black person break on that mess with some straight talk, and they get blamed for destroying all that.

JW: That's for sure! And there's a price to be paid for that.

FW: Exactly! [Laughs] There's a way in which, in the Humanities, a black intellectual/academic can put "redemption" on the table as a category of interrogation, but you can't do that in the Arts. Redemption takes on biblical proportions in that arena. It's as though they say you don't have a story if you write—or stage—a production for which there is no closure, no promise of equilibrium being restored to the diegesis.

JW: Right! Staging a diagnostic interrogation—or what I prefer to think of as engaging an audience in a dramatic diegetic analysis—is presumed un-theatrical or anti-theatrical—when, in fact, the opposite is true; such analysis vivifies the work!

FW: So here you are, someone who, as a black person, lives a life for which there is no redemption. And yet you are forced to make redemption in everything you do; to show them a world unlike your own—to spare them the "indignity" of having to encounter you. I saw you struggling with that institutional imperative, as did I, when I did my MFA in fiction writing, at Columbia. I mean I kind of believed in it—

FW: —even though I knew that it wasn't in my body, and my stories didn't go there. But when they forced it on me by showing me that my stories didn't "fit in", which is to say, when they didn't value my stories, I got pissed. [Laughter] I started to understand—even if not yet theoretically. I was doing my coursework with [Edward] Said, and as "complex" as he and Jean Franco were (they were running the Cultural Studies Project), simply because they didn't believe in bourgeoisie redemption of individuals (the way Hollywood cinema does, for example), they did believe in historical redemption of classes and of postcolonial subalterns. So, how has that "coming of age" journey been for you? [Laughter] I see your face!

JW: It has made me quite agéd. [Laughter] Seriously, I feel in some ways "brittled" by the process.

FW: Say more about that for the uninitiated, and for those who think they are, because this speaks to some of the embedded structural violence we've been suffering and alluding to.

JW: Well, the years I spent at UC Irvine doing both doctoral and post-doctoral work were intense and complicated. They were "educational" opportunities in the best and worst sense of the word. During my two post-doctoral years, I reflected long and hard upon how the scholarship to which I was exposed as a doctoral student has expanded my horizons in ways I could never have imagined. Just a few of those scholars are: You, Hortense Spillers, Saidiya Hartman, David Marriott, Jared Sexton, Dorothy Roberts, Joy James, Christina Sharpe, Sylvia Wynter, and Sharon P. Holland. And then there are some of the powerhouse rising scholars: Zakkiyah Jackson (Black Feminist Theory and Literature), Selamawit ("Sally") Terrefe (Feminist Theory and Literature), Nicholas Brady (Black Radical Theory and Debate), John Murillo (Black Radical Theory and Literature), Omar Ricks (Radical Black Performance Theory), Darol Kay (Black Cinematic Theory), Patrice Douglass (Revolutionary politics and theory), Wind Dell Woods (Hip Hop Theory), Cecilio Cooper (Black Queer Theory and Performance)—and many more I am not recalling in this present moment—who are asking major questions that severely trouble what is regarded by many as the foundational scholarship in the Arts and Humanities. I suspect some of the scholars I've just named are or will be regarded by the academy as the "troublesome supplementals"; the ones relegated to the footnotes. Well, I cherish those footnotes, and you taught me about that; the idea of the footnotes being where the most revolutionary, disruptive work happens. And that's where I find myself and where I choose to do my work. But the labor and psychic mettle it takes to call attention to the often imperceptible violence that is perpetrated in the theatre milieu, especially against those who bring theatre and political critique together to examine the power relations that define human (and de-humanizing) interplay, is immense! I realize there are plenty of writers and directors, whether they work in theatre or in film and/or television, who trouble the Aristotelian arc and catch a certain degree of hell for disrupting it. But I catch a very different kind of hell.

JW: And precisely for the reasons that you've already mentioned: I interrogate rather than reify notions of redemption. These new-age film and television innovators to whom I've just alluded are playing with the pathway toward redemption, saying, "we're the new generation of screen/stage writers. The dramatic story line doesn't have to be so linear." And while I tend to agree, that is a different project from mine—it's all about pushing the boundaries of aesthetics to tell a "better" story, to keep the audience engaged. I'm not interested in that as an end. I'm interested in the necessity for continued diagnosis and analysis through and within dramatic storytelling; otherwise we can't even begin to entertain prescriptives, dénouement and resolution—what you refer to in your work as "the restoration of equilibrium". In other words, I'm not as interested in plot as I am in the absences within it—the absences in story lines and constructs. I think a major structural project for whiteness and those who attain to it and the privilege it provides is to continue living in all of these imaginary realms enabled by the dismemberment, disembodiment—and I'm talking not only literally but also metaphorically; symbolically—of blackness. I am reminded of the big poster someone was holding at one of the Black Lives Matter events, inspired by that young Black actress, Amandla Stenberg's question: "What would America be like if [it] loved black people the way [it] loves black culture?"

JW: It seems that what continues to "trend" in Hollywood is the privileging of whiteness on the screen. Now that the virtual era has solidly arrived, there appears to be a real investment in continuing to stake a claim in the imaginary realm as a lasting vestige of white "life"... This "virtual life" and the technical acumen and abundance of resources required to execute it contribute to the quashing of the black intellectual "noise" that dares to critique that project. And it's the same in the world of theatre, I'm afraid; a world that continues to uphold a stalwart commitment to the pursuit of craft excellence, while largely refusing to confront any questions about what that craft is in service to, ethically and politically, not just culturally and artistically. What does the pursuit of "good craftsmanship" really mean, beyond the people in the last row being able to (physically) hear what is being said? Being able to isolate the head's movements or hand gestures from the body, or correctly utilize the head and chest resonators for good vocal production all contribute to good technical acumen and clear presentation. But do they constitute an ethically-engaged, rigorous-thinking, well-read performer? Because that's a different question altogether, isn't it? Don't get me wrong; I value and respect solid craft. I practice it. But again: it's not just about "telling a 'good' story," but about telling one that is vivified by thought, reflexivity, and a series of ethical questions that guide one's entry into the world of a play so as to really get the playwright's "deep-tissue" labor.

I began to awaken about fifteen years ago to the fact that a growing number of black artists were in pursuit of articulating blackness as a condition rather than as an experience. This isn't terrain many producers and artistic directors in the profession, or department heads in the academy, are interested in traversing, because of the implications and the stakes. This is because a condition implies larger dimensions, whereas relaying an experience, no matter how profound, keeps the exchange down to a "manageable" scale—a ratcheting down of the scale of abstraction, as you might say. The extent to which that experiential storytelling fulfills the demands of their subscriber bases determines whether a black playwright will have a shot at a workshop or reading in, say, a professional regional theatre. The main stage is usually even further off in the distance for black playwrights than it is for all others. So, that coveted token slot—whether it is a full production or a staged reading/workshop—is often what designates many regional theatres' "diverse" offerings. When August Wilson gave his speech, The Ground on Which I Stand, pointing to the need for a national black theatre in which black plays could be cultivated and produced to a far greater degree than they were in the white mainstream theatres, he knew very well that he was a token recipient of the big accolades and prizes. Well, he was staunchly criticized by more than a few in the industry as the well-lauded, ungrateful playwright, when what he was really doing was training a lens on a continued dearth of opportunities for black dramatists and enabling an analysis of what the source of that dearth really is; that it's not just a question of injustice or inequality, but of something much deeper, you know?

JW: So he got accused of having a black nationalist agenda, a limited purview, and of being an ingrate, rather than being recognized for unearthing a deeply ingrained, structured and institutionally perpetuated problem—in effect, a condition of virtual absence and voicelessness. And this refusal of recognition is the violence we've been talking about here. The state killing black people is an acute manifestation of it, and it's still structurally disavowed. But the tacit violence—the violence you can't prove concretely, for which you don't have tangible bodies; just intangible psyches, and a lot of "anecdotal evidence"—is at work all the time. And some of Wilson's most indignant critics were those who regard themselves as not only benefactors, but as allied progressives!

FW: [Laughter] A lot of fear rears its ugly head among our so-called "allies" when we move toward that something deeper you're talking about; something deeper than inequality and injustice, as you point out. I think of it as a fear Left-leaning artists have of what will happen if we stage a black encounter with violence. They don't want to witness our singular relation to structural violence—start in with that and they will burn you alive, as a witch at the altar of the universal. But a careful interrogation of violence is central to Afro-Pessimism. What Afro-Pessimism is saying to the Humanities, in particular, and to the world in general, is that you all have been theorizing violence in a way that skims the surface of its performances. No wonder it looks like it happens to all people who are oppressed—and in the same manner. But you haven't thought the violence that positions the slave; which is to say, you haven't thought the violence of black subjugation. And that goes doubly for Theater, Music and Art departments that like to think of themselves as being like Disneyland: "the happiest place(s) on earth!"

FW: Theatre and Drama departments, and theatres in general aspire to that—being the happiest places on earth, because one can actually play a racist, theoretically, and not be one. [Laughter.] And that's the badge of honor they give themselves, when, in point of fact, I see fewer places more violent than these artistic spaces.

JW: And I can attest to that! Again, that tacit insistence that all is well, that the liberal progressive project has triumphed over strife and that any attestation to the contrary is not only limited thinking, but dangerous! Any particularization of the problematics that haunt the world somehow constitutes deficient logic. Only universalist thinking produces a truly diverse world. The tyrannical violence of this overdetermined utopian dream is stultifying.

FW: You know, I was speaking to a black woman who got her MFA in acting here before I came—I'll have been here ten years in July. And the things she related to me—the hydraulics of anti-black micro- and macro-aggressions that she suffered here, are the same things people are suffering today. Like the issues you encounter when you're directing. No one in that situation sees themselves... They see the problem as being in Ferguson...

FW: ... or in Baltimore, But not here. And this is really interesting, because what it means is that as a black director and as a black PhD theoretician, you are, if you excuse my language, confronted with either shitting where you eat, or keeping quiet. ... [Laughter]

JW: Yeah! There's Baldwin again: the "choice between amputation and gangrene".

FW: Yeah, and it's not like it's a choice, really; it's an imperative backed by violence.

FW: And so, breaking through that imperative is, as Jared Sexton says, what happens on the other side because these are non-black liberals you are dealing with—people presumed and who presume themselves to have integrity. When in fact, Southern racists, Afrikaners, Hitler and fascists are the people with integrity, because they move along a clear trajectory. Sexton says there are three moments along that trajectory you can set your watch by: a sense of guilt, resentment, and the third move is aggressivity. It's true in dealing with the anti-blackness of the multi-cultural movement in the Humanities, because at our age—and we can say it: we are fifty-nine—[Laughter]—it becomes even more difficult. It's like our lives are nothing but "repeat scenarios." And we're in the soup in which Latinos and Asians get to perform that Afrikaner, that French imperialism, that Kennedy blockade, at the micro-level. And they get insulted when you call them on it!

JW: It is a nightmare! And having a front row seat to that horror show, and being "anointed" by its backlash here in the academy has been traumatizing, to say the least.

FW: I am finally beginning to understand what people in your position and in my actor-brother's position are faced with, because this should be a school, and actors and directors should be students first. But they're being subversively trained as though it were a conservatory. And what that means is that there's no way for you as the director to make an intervention in anti-blackness or to change what is happening any more than there is in Hollywood. So, let's talk about your productions and how you intervene, in any way you want to, because I think that this really resonates with some of the things that you experienced here, and pulled through miraculously.

The most recent was The Liquid Plain, a creative and clever, yet problematic play on many different levels. Let's talk about the problems you encountered, how you dealt with them, and how the Humanities symposium we conducted helped with that.

JW: It helped tremendously! You said something really important just now about the structural impossibility of intervening, and how the rehearsal process and all the other conventions that are so solidly set in place in the theatre did not necessarily help me. Well, sadly, that is not only true, but violently so. For example, I sat in a production meeting for The Liquid Plain and was told by a senior technical staff person, in response to me asking when I could visit the shop that "the most professional and successful directors visit the shop daily." Well, that is not something I tend to do. Rather, I entrust the designers and shop folks to their work, and visit periodically so I can get a real sense of the progression, and be delightfully surprised rather than be a micromanager of their creativities. It was such a direct and public admonishment of me and of my apparent non-adherence to protocol. And that public, spectacularized shaming is just one manifestation of the psychic violence we endure in these spaces. And in this pseudo-conservatory environment that cathedralizes European-rooted training, it is challenging, to say the least, to remain resolute in my own theoretical/theatrical approach to the production process, facing, as I am, having my sensibilities and professional rigor framed as "(un)professional" and "(un)successful," rather than as an alternative to which students have the opportunity to be exposed. I can guarantee you that if I were a visiting artist from Europe and of a different hue, I wouldn't have had to endure being shamed in such a fashion.

In terms of the rehearsal environment itself, table work is hardly a new concept in the American theatre. But sitting down at the table to really read how the political and historical implications of the play text directly impact the social ones; and along with that, moving on the presumption that actors bring brains as well as bodies to that table—brains that are capable of participating in the thoughtful rigor of such a process—well, it would appear that that's downright revolutionary! [Laughter] All I aimed to do was to open a space where the residue, substance, and fiber of that political, historical, theoretical and artistic synthesis could breathe, and, in turn, draw other elements of the play to the surface that might bring us closer to what was troubling the playwright enough to write the play to begin with.

In the case of The Liquid Plain, Wallace is troubled, in liberal earnest, by the historical fact and concept of slavery. She consulted and aligned with a particular Marxist intervention, and in so doing, omitted an entire field of consideration, which is to say, the slave's critique—not her/his/their experience. The Rediker/Linebaugh text presumes slavery to oppress all those at the intersection of transatlantic slavery. In other words, slaves and slavers alike are presumed to be exploited by the slaving industry. And so, now we have the task of disarticulating slavery's constituent elements from labor exploitation before we can even address the language of the play, which means that if the actors are on board with the play's overarching assumptive logic, then all the inflections in their performances will be influenced by that Marxist framework. This meant that we had to disabuse the actors of certain presumptions about exploitation and of what really constitutes the slave's essential condition, so they could understand that it is not at all analogous with labor exploitation. This meant that you, as dramaturgy mentor, Wind Woods as dramaturge, and I, had to do a fair amount of heavy lifting to make that adjustment. And again, it's not as if the libidinal economy is not alluded to in the play; it's there. Dembi's recollection of wailing for "his" master's pleasure is one of the linchpins of the play. But if labor exploitation and monetary profit are the "syllables" on which the "accent" is placed, this very particular exponential violence will continue to be mis-categorized as "exploitation" rather than as the undoing of human-being. And this was compounded by the fact that there was already this momentum around doing the play—one of the doctoral professors is an active proponent of doing more substantive plays in the department, and strongly recommended it, having seen its world premiere at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in 2012.

Naomi Wallace is a prominent playwright—and was generous and lovely to interact with. And as you've said, she makes some smart and highly creative moves in this play. So, the "burden of proof", as it were, was on us (me and the dramaturgy team) to render apparent the problematics of the play's assumptive logic, while also combing out its strengths. And that meant examining the function of each and every character with a cast that has entered the process primed to consider their characters' personal motivations, actions, and how those actions effect others' reactions, and so on—an entirely interactive, experiential—in essence, narrative and psychological—mode of thinking. So I had to say to them, "We've got to dig even deeper than that, and look way beyond the interpersonal dynamics of a motley confluence of individuals, toward a set of figures who illustrate a devastating architecture of power relations." I have to say this to a lot of casts, in truth, because if you are really going to read plays deeply, politically, theoretically, as well as dramatically, the actors must understand the role they play in not only an arc of human complications, but how they fit into a power structure such that the conflicts become far richer, more stunning and even paralyzing, when these different approaches to the play are acting in concert. You know how a jet can't successfully lift if the landing gear is down past a certain point during takeoff because it causes an undesired drag. And the drag on my work as a scholar-artist is the persistent, short-sighted presumption that theory and practice are incompatible in the theatre world, and that purity of craft trumps deeply dynamic, even explosive, diegesis: "thought—and certainly sober political thought—be damned!"

FW: Interesting, you said "burden of proof," which connects to something else you said about the presumption of slavery as an "equal opportunity oppressor." There's a way in which there are layers of aggression at work. Part of my beef with Edward Said, which I was not articulate or educated enough to know at that time, was that he was always moving in a situation in which the world figured he had a beef, which is not the same as saying that the world agreed with his beef. Many recognized and incorporated his beef as a valid one: "You want your land back." And he never told any stories of encounters with reasonably educated Israelis who were not alive to that. So, presumably, he might say as much to the guys he played squash with, who were sometimes pro-Israel professors at Columbia, to which they might reply, "Okay, that's your position, I understand it clearly, but Israel has a right to exist." But, given what you've said about Wallace's play, and then, moving up levels of abstraction to the table work in rehearsal and being a postdoc, and before that, a graduate student and director here, there's a way in which you were faced with this kind of refusal to recognize a black beef that is embedded in everything, at every level of abstraction.

FW: Wallace's play disavows that and so, again, we come back to violence perpetrated through not recognizing how the violence the press-ganged sailor receives and the violence that the Irish national receives cannot be analogized with the violence that the black slave receives. And the belief that they can be protects the non-black psyche from actually meditating on the beef that black people have, which actually can't be resolved. And then, we have to fight against that. It's not an argument, because in drama departments and the art world more generally—and I know from my brother in Hollywood—and sadly enough, even in the world of creative writing, people don't argue. They feel. [Laughter.] And if you say to someone, "explain that more", they'll just give you deeper passion.

FW: So we have a situation in which their notion of performance theory and drama theory suggests that there's something cathartic about the dramaturgy and the dramatic experience that will lance a boil and all the puss will come out. And what you're saying is that not only is there an absence of catharsis, but there's an intensification of the wound in the very process of performing something that is supposed to be cathartic.

FW: And that is largely because they're not going to connect the dots between, say, writing plays and Baltimore; and Baltimore and slavery. There's a hydraulics—an imperative against connecting those dots, and that's what you walk into as a director.

JW: Every time. And the other aspect of these strange symptoms is that, as you're acknowledging that the wound is deepening and saying, "so let's just go deeper into it," you get sutured to that wound and are then seen—"cast"—as the antagonist for wanting to analyze rather than feel what's inside of it—for pointing out the necessity to enter it at all. You become the reason for that wound being there, and treated antagonistically: "we don't understand why you're so upset. Why does it have to be this complicated? Why do you always want to feel bad?" You become the boil that needs to be lanced!

JW: So this presumption is foisted—over-determined—onto you, that you're obviously committed to feeling bad, instead of to the more progressive mission of peaceful, all-inclusiveness—of universality. And worst of all, the work you're doing gets reduced to that undesirable "structure of feeling" that you talk about in your work. It is one of the most formidable trip-wires in navigating my own work as a scholar-practitioner.

JW: What I'm really doing, and what you do in your work, is to report on and render an analysis of these antagonisms—I'm mindful of the distinction you made earlier between the Humanities as a locus of reading, and the Arts as one of feeling. We are not being the antagonist. And yet, part and parcel of the violent erasure of the black reporter, is that process of being fastened to the wound and saying, "we don't want to feel that" and "we don't know why you're so obsessed with staying in that place instead of getting on board with the rest of the multi-/inter- racial/cultural world that is looking for resolution". This is a direct result of the "tyranny" of feeling over reading. So, whether you're working in the field of theatre and drama, literature or cinema, you get hit from all sides, because there's no shortage of black folks who are sold on—and that's not an accidental choice of words either— [Laughter.] ...who are sold on, and quite committed to, resolution, redemption and hopefulness. And I have enormous compassion for that, actually.

JW: Exactly. We all want to live. But what's disturbing me about this 21st century phase of the same old antagonism is that to add to all these other refusals, our intramural conversation has become not only more complicated, but incredibly rife.

JW: Black folk have always had philosophical differences, but it's far worse now.

JW: Yeah. Under the press of "progressive" positivism.

FW: You know, when I was writing my dissertation, and Saidiya Hartman and I would meet for coffee to go over chapters, I would imbibe her fear, and fear is not too big a word. And I would see it in myself, too. And she once said to me, "You can't go after white leftists".

FW: Because then we won't have anybody.

FW: But it was really interesting because actually, she didn't mean "don't do it".

FW: She meant, do it, but god damn! [Laughter] And what you are saying is really a part of that, because that whole thing about, "what's wrong with your attitude?!" is not an opinion; it's another imperative.

FW: Because it's subtended by structural violence.

JW: Right on! The violence of keeping everything exactly as it is, under the ruse of desiring "change".

FW: Because if you say to them, "what's wrong with your fucking attitude?!" See, that's an opinion; just another black person being annoyed. [Laughter] And see, when they get annoyed, they call the police, you know! [Laughter]

JW: Look out! Yeah, I know. Oh man, this is all so huge.

FW: And so, as we move through this, we try not to annoy them, and that means that sometimes we can be freaked into thinking, "Well, maybe it's just about needing more information." [Laughter] I did a talk—I told you about this—at the Qilombo Community Center in Oakland. There were 80 people there. Between 15 and 22 of them were white people who had come from UC Davis and UC Berkeley. So it was a really weird set-up because you have, like, 60-odd people from the 'hood'. [Laughter] And then these kind of white "adventurers". [Laughter] They're Leftists, but ... And at one point, the guy who ran the event stopped me from talking and he said, "Excuse me, but this is a Black-centered space, and I see that African people are standing and Europeans are in seats, so will the Europeans please sit on the floor." And so, I saw this one professor, you know, from Davis, kind of look around like, "I know he's not talking about me," and the organizer just kind of waited 'til the cat joined the concrete floor with the grad students and the other white professors. [Laughter] Now, at a certain point while I was talking, I said, "You know, I wake up every day and I just hate everything and everybody." And the black folks erupted in a kind of cheering, as if to say, "I know, I know!"

FW: And the white people were kind of looking around, you know, like we had soup water on the boil and they were going to be our meal. [Laughter] I wanted to say, "We're not eating tonight, don't worry, nobody is hungry here." [Laughter] And I thought to myself, Well goddamn! UC Berkeley is just, like, five miles from Oakland. It's not that they don't know, it's that you're not supposed to say it when they're around! So, there's this pressure to not speak the truth of this dynamic. It's like, you can't be incorporated. You know, how you talk about August Wilson's dilemma after he spoke up at that conference. If you try to do something for black people, then you get labeled. And yet, you have to be incorporated, the way Naomi Wallace does it, by having slavery be just another form of oppression, as opposed to what it really is: the center of gravity of everybody's lives.

FW: And even kids in high school know this, 'cause they don't hang black when it's not "right". It's not like immigration, for Latinos, it's not like the term "Indo-China". Those are horrible things. But they do not constitute the center of gravity. And so they're not bringing an analysis to what renders them distinct. And then, when they're called on it, they bring in the guns. And the people who've called out this "intuitive conflation" are sentenced to "black time." [Laughter] David Gilbert got "black time" for being with the BLA, you know? You just don't want to get too close.

FW: So, let's talk about the first production you did at UCI, The Colored Museum. And then we'll try and touch on the second, The Trial of Dedan Kimathi. I'm particularly interested in the polarity between The Colored Museum and The Liquid Plain. In The Colored Museum, for the cast you were working with, it really didn't matter, and I say this cautiously, that you got that kind of push back from black actors who yearned for redemption, 'cause, as we were just saying, we all yearn for redemption and incorporation. But ultimately, everybody is going to have their "nigger moment" [the traumatic recognition that they are, in fact, not incorporated] and you just need to wait for them to have their crisis within the course of the production. Once they do, then you can work with them, because now they know they're in the hold of the ship. So, what I'm saying is, that you've got both an all-black cast and a play that are working with you in the recognition of that, sooner or later.

FW: On the other side, you've got The Liquid Plain, in which you have a mixed cast and a play that's working against you, in the ways we were just discussing.

JW: [Sigh] Yes. It was formidable.

FW: Yeah, it's always a distended calculus when a non-black person is in a room. What I mean is, the calculus is different. You talk differently. But in some spaces, there's negotiation and in others, there's not.

JW: Yes! With The Colored Museum, the texture and mode and timbre of how I had to labor were completely different because I'm dealing with black people, and young, vibrant black people at that, who are, in many respects, already thinking that they're incorporated.

JW: They don't know the deal yet. I mean, they know they are in a statistical minority—that their presence in the Drama department, and by extension, in the university overall, is disproportionately low—but they don't yet overtly perceive that disproportion as symptomatic of something larger and deeper—something that is "vertically integrated," to borrow your phrase.

JW: Right! And what they know at 18 to 21 years of age is that living life and breathing are about experience, you know. They're having an experience as young people, and this is the higher education phase of that experience. So, to facilitate their "descent" into the dramaturgical process—into the ship's hold—was ... well, all I can say is, it was amazing good fortune that you and I got to work as a team!

JW: Oh, it was incredible. It was really about being there for them as they awoke to the world through our reading of the scholarship [about slavery, structural violence and antiblackness]. And when they'd have those "nigger moments" and were like, "oh my god!" ... it was devastating. Beyond anything the "theatre experience" is prepared to explain.

FW: It was. It was. They cried a lot.

JW: They sure did. But we were there for them.

JW: In the only way that we could be... to be able to say, "We know. We can't rescue you. But we know, and we share the navigation of this 'bad news' with you."

FW: 'Cause it don't get no better in your fifties! [Laughter]

FW: We didn't always tell them that. [Laughter]

JW: No. And in The Liquid Plain, the black actors had those same moments of realization. What made their job different (and difficult) was that they were navigating their own processes of fitting theory to character—often feeling quite isolated—, and then witnessing my constant "battles" with the white actors.

JW: And I don't mean the white actors were physically or even stridently "combative".

FW: Right; you're talking about the "battle" of their affect.

JW: Yes! The earnest insistence that recuperation of all this fallout of Transatlantic slavery is possible for everybody; that we're now living in a "different" time—a post-slavery/post-racial era; and in some cases, their insistence that all this theorizing is somehow getting in the way of things. I would have to continually argue that in fact, the theory is what is keeping us on point, because what we've got is a rudder that's making the navigation of this big old slave vessel really difficult; that rudder being, again, the philosophical alliance that the playwright has formed with the notion of slavery as a project of primarily labor exploitation.

In short, that battle rarely let up on me—there were small triumphs, when the actors would realize the problem was not about through line or character arc, but about assumptive logic. But it was exhausting. Also, by this time, I'd been on the UC Irvine campus for nearly seven years, and what was happening increasingly, and apropos of everything we're talking about here, was that the more outspoken I became about my scholarship, the more tacitly hostile many around me were becoming to my presence. And that's tricky, because I'm met with smiling faces, but meanwhile, the reflection I catch in a mirror, for example, unbeknownst to someone who wants me to think they're an ally, tells a very different story. I've been thinking a lot recently, about a musical I would love to direct in the next couple of years, by Kirsten Childs, called The Bubbly Black Girl Sheds Her Chameleon Skin. [Laughter]

I guess that would have to be my trajectory here, right? I mean, that is why I came back to school, to find what I knew I needed: a language with which to intervene in the formidable determination of anti-blackness. And true to form, the more robust my dramaturgy as a director became, the more disconnected I was rendered, albeit tacitly, from any sense of incorporation into the theatre "family" here. What I'm saying is that it became abundantly clear that I had "stayed too long at the fair," as the saying goes—just by dint of training our gaze upon the hauntings of anti-blackness and on the "good-intentioned" will not to see its particularity. And when you know that, because it's everywhere, and because you've become a really astute reader, yet nothing avows what you are reading, except those who share your predicament (and perhaps some of our more enlightened allies) you realize you are standing in the eye of a firestorm of psychic violence passing for good faith. And what can I say? That's been really difficult in the aftermath of the three productions I directed at UCI. I walked around feeling the disaffection of and from the very place that had been my intellectual sanctuary. If that's not a paradox, I don't know what is. And to be assured that I will always be offered support and "love," when the whisper campaigns and closed-door conferences (the ethers of which have wafted back in my direction telling a very different story) have persisted, has been at moments terribly confusing, and at others, devastatingly revelatory. In short, it has afforded me a painful, yet crucial lesson about just how deeply-seeded anti-blackness really is. It does not see itself reflected in my analysis because it does not see me as anything but a troubler of the order that constitutes, and is determined to uphold, it. My experience at UC Irvine, and how it culminated, has also confirmed for me that when you do this kind of work, and you are ultimately regarded as the person who is the wound; who is perceived to be the problem ... okay, let's talk in the emotional register for a second—

FW: It's not a bad register, it just tends to dominate things. [Laughter]

JW: Yes, it does. But let me just say, that what my family wanted for me was the ability to work as hard as I could, to make whatever discoveries I could make along my trajectory, and the payoff would be that when I became really good at what I pursued, I'd be gratified by, and perhaps even lauded for my achievements—this is, in large part, what incorporation and recognition is all about: being recognized for making the realizations and discoveries you have made through your work. And if some have critiques of it, then those critiques are cogent, insightful, and most importantly, engaged with what you are aiming to discover or expose. Well, my family members are all gone now, but I'm pretty sure they would be quite disheartened to see that all my hard work has actually had the opposite effect, in some respects, you know? Not everywhere. Because, blessedly, there are those who do get what we are doing; with whom our work, and that of the constellation of scholars I named earlier, does resonate—loudly. But what I've had to wrestle with is the leap one has to take in trying to learn to inhabit the antagonism, because this is what the work piques, and because this is what the world imposes and is.

I knew a long time ago that Broadway and Hollywood were not my "Meccas". I also knew there was going to be a turn in the road; I just didn't know what the nature of that turn would be, until I found myself face-to-face with it and knew unmistakably that I was embarking upon a difficult, unpopular path. I was getting my MFA in Playwriting at NYU, and I encountered a stunning enactment of violence in a seminar on "collaboration", of all things. In that seminar, I was the target of a kind of public spectacle—a symbolic lynching. (I'm mindful, of course, of its repetition in that production meeting I told you about earlier.) I was repeatedly accused of "reverse racism"—a phrase that reeks of the absence of thought, especially when it is directed at black people who have yet to gain the reparative, structural power to exact racism against anybody. That black woman outside Columbia that you talk about stands as a beacon for me. Because as we know—and she knew— racism is an ordered, structured enactment, or series of them, that very specifically positions black people outside the parameters of social access in ways that are not only insidious, but also distinctly different from how racial and ethnic discriminatory practices position other people of color in lowly positions on the hierarchical, societal "ladder"—which is to say, within that societal structure. What we face is not an ethnic bias or ignorant opinion about a group of people—which, as we know, is no picnic. It is reprehensible that Mexicans are doing landscaping labor all over Orange County for sub-standard wages, in unrelenting, 90 degree heat. But wage inequity and its discontents constitute a red herring when it comes to confronting the accrued rage of blacks, who August Wilson paradoxically called the "unwilling immigrants" in the (curiously unpublished) original introduction to his play, Fences.

The anticipatory fear of black rage is a perennial state that (also paradoxically) both reifies the positioning of blacks outside of the wage equation, and masks their real predicament by posing wages as constituent to, rather than symptomatic of, that predicament. This camouflages the crux of the matter: the fear of black rage, which is motivated by a pre-conscious cognition that blacks have something deep and long-standing to be enraged about! And any moment might constitute the very funneling of revolution that keeps "civil" society and its gatekeepers animated by that fear—the kind of fear that makes empowered cops shoot first—to kill, and an unreasonable number of times—and declare later how "under attack," how afraid for their lives, they felt.

I had basically plucked lines out of a real-life situation and put them in the mouths of a couple of characters in a ten-minute play I'd written for the seminar in order to illustrate how anti-black violence performs in and through the law. And the price I paid was not only that one of the actors in the cast hated portraying an implicated character, and accused me, publicly and with contempt, of "stereotyping white people" in my dramatic rendering; but also, his public indictment set a brush fire in the plenary session, and a sizable number of those graduate students, many of them white men, began to verbally malign me unmercifully. And here's the kicker: the person who was overseeing the seminar did nothing whatsoever to stop them. And all I could think was, oh my god, if this was all playing out in an alley somewhere, it would be exponentially horrific. It was bad enough in a "controlled, civilized, pedagogical" environment. It was what confirmed that the MFA could not be an end point for me; that it's not just about being a credentialed practitioner and teacher—an expert craftsperson—it's also about interrogating what it is I'm teaching, and how I'm going to teach it through its implications, repetitions and enactments. And now I realize I have to live with the fact that that will be at some cost to me. And the cost, among other things, is that the response to my work will likely be more antagonistic than it will be laudatory, as my family would have wanted, and in ways that, to add insult to injury, are not easily provable.

FW: Yeah. You know, you talked about sanctuary, and it seems to me that there's an absence of sanctuary for those of us working through Afropessimism, regardless of the fact that people are doing so many wonderful things with it. And this is a problem that you don't find in Marxism or in white feminism. You can find sanctuary as a theoretical construct of the past—Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt's work, from the Gramscian era. But sanctuary can't exist now because, as Feldman says, the world is now in this post-industrial phase, the command modality of capital is everywhere and so, civil society has withered away. But, there's still the memory of sanctuary. And that's precisely what we don't have—that memory of sanctuary that's been passed down as something to be regained. And so, here we are, with no sanctuary in the present and damn sure no sanctuary in any kind of future that can be written about, which means that there's a kind of absence of what could be thought of as a narrative arc to our very existence. That's a totalizing violence.

FW: And so, it's not a violence that comes when something happens, or comes at a certain period in time, or is over here and not over there. I mean—to you, it's not new—it's vertically integrated. But to a lot of readers, it's still not something they can wrap their heads around intellectually. I think everybody in this country and everywhere I've been in the world wraps their heads around it intuitively, which is why blackness is so energizing, whether it's negrophilia or negrophobia. The energizing capacity of blackness is just infinite because it's this locus of violence from which respite cannot even be theorized. And the love songs are about wanting to be loved in a space that, you know... so that's why white people fuck on screen to black music and not to their own.

FW: I mean, because that authenticates the orgasm, a kind of pure jouissance. But the thing we don't say, and I'm not admonishing you or me for not saying this, is that we imagine a reciprocal violence that will take care of this, and so we kind of stunt our own voices about that, 'cause every time I move toward it on the radio, they're like, "What do you mean by that?"

FW: And I'm getting to the point where I'm going to say, "I don't know what I mean; I don't give a fuck what I mean." In East Oakland, they actually understood what I meant, and nobody asked me that question. Those twenty white people sitting on the floor didn't ask, "what do you mean by that?" ...

FW: ...the way they did at Berkeley the night after, when they were in their territory [Laughter]. And it's not because they actually want to know, because if they did, I could be a figure of authority, by which I mean, someone through whom a discourse of authorization flows. Obama can't be that person.

FW: [Marilyn] Mosby [the black Baltimore State's attorney who withheld evidence in the death of Freddie Gray], can't be that person. And, I mean, what cop doesn't love a prosecutor?

JW: [sigh] Yeah, right? And yet...

FW: ... she can't be that person. And you can't be that person in the theatre.

JW: Oh, I know. I was actually "reassured", in my exit interview, that while "[I] may not be able to teach or work from the center of the field, there are people over at the margins who [I] can work with."

FW: That's really... [pause] that as a director, you can't be the locus of authorization.

JW: I know ... Nor as a professor, you know?

JW: Yes. I've already seen signs of that.

JW: Well, this is such an important thing, and it circles back to that point you made about violence, and this censoring or, circumscription of black people as a mode of violence. And we were talking before about the complexity of the intramural conversation and how that troubles me so deeply.

JW: Yes. Black to black, I should clarify. Something Hortense Spillers has been inviting for a long time, as I alluded earlier, but for so long had no one with whom to engage that conversation in the early days when she was out there all by herself intervening in the field of literary criticism. And now that so many of us are, we've got these landmines everywhere among us, that continue to trouble our pathways; not least, our conversations with one another about this issue of authorization and its refusal to us. I mean, my Mom was a die-hard black democrat: buy black, vote black, support black, do everything black. Sounds pretty Black Nationalist, doesn't it? But this is paradoxical, because there was still this dream of belonging to a larger context that would one day, somehow, land us beyond where you and I are now, in 2015. We marched on Washington in 1964, in quest of that. How old were we then?

JW: Right. That was fifty-one years ago. Hoping to be light years beyond where you and I are now, at age 59! It was so important for us to show the world that black people are good, capable, civilized, respectable—everything the world persists in thinking we're not. And today, that need to affirm, "I am somebody," I am not socially dead!" continues to reflect an investment in the idea that wishing we're not susceptible to these structural, embedded violences somehow makes it so. Attendant to this is the two-fold liberal progressive insistence that (1) this is all redeemable through positive activism, good will and a recognition of universal human incorporation; and (2) perhaps the most terrifying of all: if I am doing my liberal due diligence, I am immune to implication in the perpetration of such violence.

I think "the theatre" community is often a breeding ground for the bitter contempt of our thoughtful, rigorous artistry; a contempt disguised as "earnest" befuddlement and "loving" support. And as I have gotten more in touch with just how deeply this violence is impacting me in these spaces in which I have been trying to be a rigorous artist, I am mindful of that question Jared Sexton poses, invoking a difference in inflection with which to think about violence-as-revolution/response: "How can we be ethically opposed to some forms of violence while being in favor of others?" And then you just change the inflection of that to: "How can we be ethically opposed to some forms of violence while being in favor of others?"

JW: I never used to think like that. But now, my thinking is quite different, and it's now possible for me to conceive exactly how, you know?! I went to a public talkback for one of the UCI shows and asked a question about how racial dynamics were broached during the rehearsal process. I had observed that, in contrast to the idyllic lovers and noble characters, the black figures were consistently perpetrators of sexual impropriety (incest, for example), power abuse, corruption, and so on (the play was a well-known mash-up of Greek myths). I was thoughtful in formulating the question, and even complimentary of the director in the process of posing it. Well, the director not only emailed me to point out the inappropriateness of my question (claiming the focus of the talkback was on design rather than on directorial concept), but also confronted the black actors (who responded enthusiastically to the question), nonplussed that they had never brought their concerns up in rehearsal—never considering whether they'd felt welcomed to do so! I see this shaming and rebuking of black people who call out unconscious antiblack racism, as violence. And it is epidemic. And don't you know, that talkback "incident" is apparently still being talked about, yet not a word has ever been spoken directly to me since, except by the actors, about it. That "radio silence" is a part of the violence; it constitutes the masking/camouflaging of the gestures. Yet we clearly perceive and suffer it all. And it is devastating and enraging.

FW: I think we can give ourselves permission to act. I think we have the responsibility to be irresponsible. Now, that doesn't mean that you or I can ever or always do that—and what does that really mean? You know, I remember while I was a grad student, and still doing course work. It was 2001, and I was teaching a course the morning of 9/11. What's interesting is that I was standing outside the door and the undergrads were walking down the hall (it was a large class). I was team teaching with another grad student and as the undergrads were coming towards us, I could see a kind of dejection in the whites and Asians, and a bounce in the steps of the black kids, you know? [Laughter] And this is where your radical teaching comes back to bite you in the ass, you know? [Laughter]

FW: So, they came up to the door and said, "We did that shit, right?" Now, this is an existential moment for me, because they wanted to slap five, you know, at the door, and then my brain kicks in with: "I'm responsible to all these kids." But it was more a fear,'cause you know, my ex-wife in South Africa told me they had dance parties around 9/11. I mean, the things that were not being reported were black people around the world who are suffering from Muslim aggression and suffering all this other stuff, yet were still cued in to the energy of a bomb going off that big in the United States. And so, here I was, so goddamned "educated" that I was going to discipline the energy of the black kids until we found out exactly what happened. But fortunately, something kicked up in my mind and I just held my palm up and everybody just slapped it on the way in.

FW: But it wasn't groovy, okay, [Laughter] 'cause now I had to teach a class of about 15 whites and Asians who had just seen that shit go down, you know? [Laughter] And they wanted to hold me accountable for that gesture. But I was, like, wait a minute, if an apartment building or something blew up in Nazi Germany and a bunch of Jews and gentiles around the world were just clapping, they wouldn't say, "Who are the innocent people who died there? Let's figure out who put the bomb there first..." It'd be more like, "Something popped off in Nazi Germany and we're just happy. So let's just live in the happiness of the violence against the Nazis now, and we'll figure out the other shit later," you know? But that's a criminal act as a black person.

FW: And I'm trying to get to a point where I can perform that without, you know...

JW: Mmm-hmm. 'Cause the academy has deputized us to quash ourselves.

JW: But again, the beacon for me is that homeless black woman that you talk about in the beginning of Red, White & Black...

FW: Oh yeah, at Columbia. [Laughter]

JW: ... who was out there going: "Give me back my shit!"

FW: And waking up the black kids. [Laughter]

JW: That's right. And she knows the deal, because being on the street schools you in a whole other way.

JW: She knows that there are high stakes for black folks and that, yeah, you've crossed this line, and so now, you're walking into one of the most prized institutions around, so you (black people) can't avow my signifyin'.

FW: You know where Columbia is. Some people who are reading this might not. It's Harlem, upper west side, but it's all "chichi" now. And they're pushing the black folks in Harlem further and further north, so there's a lot of angry black people up there.

FW: When I was there, '89 through '91, there were some—and I'm not condoning this, but I'm not not condoning it—but there were black girls in high school who were feeling the pressure of Columbia's presence, just like every other black person in that area feels it.

FW: And they would walk up and down Broadway between 96th and 125th and they'd stab people with hypodermic needles and say, "I just gave you AIDS."

JW: Wow. Yeah, I remember hearing about that!

FW: And that was funny to them. [Laughter] I think it's funny too! [Laughter] You know what I'm saying. And we'd laugh about that shit in the Black Student Union and the Black Graduate Association, you know? You'd get into class and they'd be like, "Did you hear about that..." and we'd fold our arms and knit our brows and get all "hmm... oh, they shouldn't do that, indiscriminately stabbing people?!" But see, they're not doing it to black people, [Laughter] it's just white professors... and there was nothing but water in these hypodermic needles. But they've been called AIDS, see. AIDS is black; black is AIDS.

FW: So they said, "Okay, so, we're going to give this back to you." And no one was willing to take that up as a mode of resistance or as a critique of dominant civil society. It was just a criminal act.

FW: And then, here we are as graduate students and black professors, forced into simply thinking it as a criminal act, in the university, and laughing our heads off at our little block parties. [Laughter] But no Palestinian would have to deal with that shit. They would understand, a suicide bomb, well, yeah, they're mad 'cause their shit has been gone for sixty years! Really? Give me that struggle! I'd be in heaven!

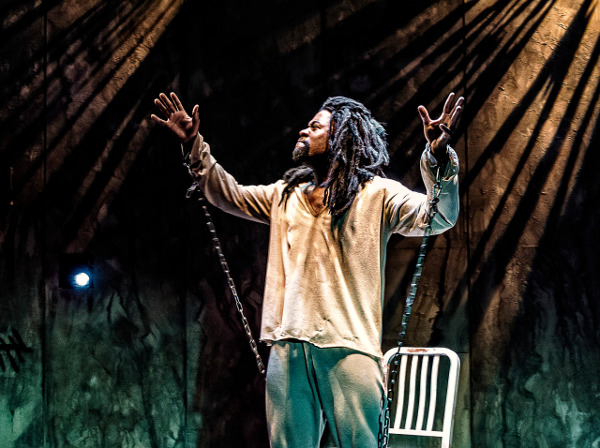

JW: And that's the "Boom!" on that. You know, what you just recalled made me think about the first time I read The Trial of Dedan Kimathi. I was so deeply moved by the radical response of these two young scholar-activists, Ngũgĩ wa Thĩong'o and Mĩcere Gĩthae Mũgo, in 1971. I could picture these two enraged black people in Kenya, who were just pulling the pins out of their proverbial grenades, using words to rail at this stuff—there's that Sexton question again. And what was important for me, from this side of the ocean, all these years later, is that we know when we talk about "slave time" or "black time," what that means, you know—how much time has passed, yet how time hasn't passed at all—to really recognize that those two young people in 1971 still had cause to rage in 2014, when we performed the play. So that rage was the beacon that kept me on point —that spark, the ignition switch of their treatise—their manifesto. Not the promise of transcendence or redemption. Their rage was rightful, not righteous, but right indignation. They were building a context around the figure of Dedan Kimathi as someone who was enraged, on the move and able to galvanize black people into a "moment" of action. The outcome is another story. I mean, first, the British killed him. But more than that, look at the world's relationship to Africa today. Look at the fact that this play is still relevant. I mean it all speaks for itself. The evidence is all there. James Baldwin's invocation of that biblical phrase, "the evidence of things not seen," for his last book about societal law and jurisprudence and what it really means in relation to black people; the implications of how Wayne Williams was tried for the murders of all those dead black children. That's what broke Baldwin's heart and his spirit ...'cause he was dead in a year.

JW: So, those are the things that kept me on point with my direction of The Trial of Dedan Kimathi. Whatever the machinations surrounding that production—and I am writing about those—I just had to stay true to the vision of those two people in 1971, who are both alive today and still fighting, and to my vision of how best to bring that rage crashing into the strange oblivion of Orange County, California that the UCI campus exemplifies. So, I had to assume the burden—thinking of Saidiya Hartman's concern with the re-production of violence – of dramatically staging the violence these Kenyans endured. And in so considering, I chose to abstract away from the literal, for greater and lasting effect. I sat the audience in the midst of it, surrounded and implicated by it, in every way I could think of—I wanted to engulf them in it, in order to render Kimathi's and the Kenyan people's resistance unequivocally present, even in its ephemerality. Theatre is ephemeral because it comes and goes, it's here and then it's gone. But I wanted to create an immutable palpability within that ephemerality; one that would remain as haunting residue after the stage pictures were gone. There were a lot of machinations going on around that work in terms of [sigh] the "hopeful" thrust of a lot of the post-colonial discourse—the notion that triumph, possibility and futurity are all awaiting black people. I had to stay true to my attempt to collapse past and present together in a dramatic and dynamic way—in order to depict the truth—the "history"—of the present. So that at the end of the play, the audience can't just jump to its feet in a fit of catharsis declaring, "Yes! Triumph is ours!" This past year right here in the U.S. has revealed just how collapsed past and present really are, and just how far from triumph we really are.

FW: You did that really well, because you mined the unconscious of that play in a way that I think the playwrights were really happy about.

FW: I mean, it's like the pre-conscious level of the play is kind of like the discourse I encountered in South Africa where people were like, "here's what's happening, but we're going to be free one day." And yet, what you saw and brought right out in the open was that the word slave was in that play about 12 times.

JW: Yes, I did. And yes, it was.

FW: One of the great things that you did in directing that play and through the table work was to educate the actors about how the paradigm of post-colonial subjugation is mapped onto the paradigm of social death and slavery. The play knew that intuitively, and you brought it out in the direction. I think that was really, really great.

JW: Thank you, Frank. And I was swimming upstream against the... "tyranny of positivity," among other things.

JW: I love the myriad of insights you've provided me about "tyranny." The tyrannies are endless. And the tyranny of positivity is formidable because it has wedded so many of us to this outcome of freedom. What many people still don't understand is that interrogating these notions of freedom is not synonymous with being against freedom...

JW: That's the grave misapprehension that people have about Afropessimism as a theoretical framing—that we're somehow against freedom; that we think black people are inherently slaves, incapacitated, and so on—when what they need to understand is that the lens of that critique is trained on the world, not on black people; not on their hopes for freedom or their desire to live and be alive. Those of us who use this framework take black people's multifariousness as givens. Rather, we analyze the terrible tension between those hopes and what bears down devastatingly on them, recognizing that, whether through creative or theoretical literature, including dramatic literature and dramatic practice, we have to stay the course of our ongoing critique, even in the face of its constant quashing. And that's what I'm doing with my work.

JW: As are you, Doctor Wilderson.

FW: Well, thank you, Doctor Williams.

— Irvine, California, May 12, 2015

Notes

- George C. Wolfe, The Colored Museum (New York: Grove Press, 1985). The UC Irvine production was presented in March of 2011, directed by Jaye Austin Williams, with Frank Wilderson serving as dramaturge. It received its world premiere at the Crossroads Theatre Company on March 26, 1986, directed by Lee Richardson; and later opened on November 2, 1986 at the Joseph Papp Public Theatre, also under Richardson's direction.

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o and Micere Githae Mugo, The Trial of Dedan Kimathi (London: Heinemann, 1980). The UC Irvine production in March 2014 marked the American premiere of the play, which had been previously produced in Kenya and in Europe.

- Naomi Wallace, The Liquid Plain, to be published March 2016 by Theatre Communications Group. The play was developed and received its world premiere at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, on July 2, 2013, and its regional premiere at UC Irvine in March 2015.

- Williams is currently at work on a monograph analyzing these three processes.

- Williams regards herself as a drama theorist who is, to some extent, in conversation with Performance Studies, a field that is engaged historically and, to varying degrees, theoretically, with cultural performance practices (theatrical and otherwise) and how people of various racial and cultural identifications are impacted by their social and geographical positioning. However, while she is strongly engaged at the intersection of theory and practice, she is impatient with many praxis discourses because she observes them to elide a rigorous political critique.

- Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982). Patterson isolates the three constituent elements of slavery (i.e., elements not merely characteristic of, but inherent and necessary to the process of slave-making) as being subject to: (1) absolute/total violence, (2) natal alienation; and (3) general dishonor. (pp. 1-7)

- Representative/influential texts include: Red, White & Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms (Wilderson); Black, White & In Color: Essays on American Literature and Culture (Spillers); Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery and Self-Making in Nineteenth Century America (Hartman); Haunted Life: Visual Culture and Black Modernity (Marriott); Amalgamation Schemes: Antiblackness and the Critique of Multiracialism (Sexton); "Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction and the Meaning of Liberty (Roberts); The New Abolitionists: (neo) Slave Narratives and Contemporary Prison Writings (James, Ed.); Monstrous Intimacies: Making Post-Slavery Subjects (Sharpe); "Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom: Towards the Human, After Man Its Overrepresentation—An Argument" (Wynter); and "The Last Word on Racism: New Directions for a Critical Race Theory" (Holland).

- See Red, White & Black...; also see "The Black Liberation Army and the Paradox of Political Engagement" for several references to this term.

- August Wilson, The Ground on Which I Stand (New York: Theatre Communication Group, 2001). In June 1996, Wilson delivered a keynote speech at the Theatre Communications Group's biennial conference, in which he called for a national theatre specifically dedicated to plays by people of African descent. After the speech, a number of regional theatre artistic heads and members of the national theatre community viewed Wilson as a kind of "turn-coat," who was, in essence, biting the hand that fed him, having been a playwright who had reaped the industry's many benefits— grants and fellowships from organizations such as the National Endowment for the Arts; two Pulitzer prizes—and now, was critiquing the theatre arts community for not doing its part in supporting Black artists more broadly.. Correspondingly, when Williams was approached by a Black graduate student at UC Irvine, requesting that she teach a seminar specifically for black MFA actors on Wilson's canon, the course was approved and she taught it successfully, but not without a surrounding climate that flared with accusations of "academic exclusion", "reverse racism" and the like. The black graduate students put forth that in the event they were cast in Wilson's plays, they didn't feel the curriculum in which they were currently immersed was adequately preparing them to read his works at all, let alone, deeply enough to understand how he was elaborating black suffering. Williams is currently preparing an essay entitled, "The Subtext Uttered: Exposing 'The Theatre' as Metonymic Anathema to Black Dramatic Critique," analyzing these antiblack embedments in academia.

- A widely cited quote by Baldwin about the condition of the Black as "always being in the position of choosing between amputation and gangrene."

- Dr. Wilderson conceived of, curated and moderated a two-day symposium in the UCI School of Humanities entitled, "The Liquid Plain and the Enduring Dynamics of Racial Slavery," featuring a conversation between Wilderson, Williams and Wind Dell Woods, the production's dramaturge. It also featured papers by Nicholas Brady, Doctoral Student, Culture and Theory; Dr. Sora Han, Asst. Professor, Criminology, Law and Society; Dr. Karen Kim, Senior Lecturer, African American Studies and Gender and Sexuality Studies; Selamawit Terrefe, Ph.D. Candidate, English; Dr. Rachel O'Toole, Assoc. Professor, History; and Dr. Tiffany Willoughby-Herard, Assoc. Professor, African American Studies. There was also a Q & A with cast members Jessica Mason and Jade Power. The symposium enabled a conversation designed to foreground slavery's residue in modernity, and to trouble the notions of slavery as an "equal opportunity" oppressor, and of multiracialism as a redemptive panacea.

- There are two texts in particular that appear to have influenced Wallace's penning of this play: The Slave Ship: A Human History, by Marcus Rediker, Viking, 2008; and The Many-Headed Hydra: Sailors, Slaves, Commoners, and the Hidden History of the Revolutionary Atlantic, Beacon Press, 2000, which Rediker co-authored with Peter Linebaugh.

- In Red, White & Black, Wilderson deploys the term—originated by Raymond Williams to describe a machination that is "as firm and definite as 'structure' suggests, yet it operates in the most delicate and least tangible part of our activities." (Williams, The Long Revolution, Chatto and Windus, Toronto, 1961, p. 65)—to contrast the structure of feeling that shapes the anti-violent posture of the liberal progressive ideal, and that of the black liberation move toward the obliteration of black subjugation. (Wilderson, pp. 129-130).

- This alludes to Hortense Spillers's essay, "Black, White, and in Color, or Learning How to Paint: Toward an Intramural Protocol of Reading," after which the collection of her essays, Black, White and in Color: Essays on American Literature and Culture is named. In this essay, Spillers suggests a mode of "reading" that productively "discomfit(s)" the reader with, among other things, an essential question, "how do 'look alikes' behave toward one another?" (Black, p. 278).

- David Gilbert was a member of the Weathermen, which later became the Weather Underground, an outgrowth of the seminal Students for a Democratic Society. The Weather Underground allied itself with, among other movements, the Black Liberation Army. Gilbert was imprisoned for a series of explosions. See his 1998 video interview with Sam Green and Bill Siegel. «https://vimeo.com/35600000»

- Kirsten Childs. The Bubbly Black Girl Sheds Her Chameleon Skin. (Dramatist's Play Service, 2003). Williams is slated to direct the musical at California State University, Long Beach, in Spring 2017.

- Frank Wilderson, Red, White & Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 1-2. Wilderson recalls, "When I was a young student at Columbia University in New York there was a Black woman who used to stand outside the gate and yell at Whites, Latinos, and East and South Asian students, staff, and faculty as they entered the university. She accused them of having stolen her sofa and of selling her into slavery. She always winked at the Blacks, though we didn't wink back. Some of us thought her outbursts bigoted and out of step with the burgeoning ethos of multiculturalism and 'rainbow coalitions.' But others did not wink back because we were too fearful of the possibility that her isolation would become our isolation, and we had come to Columbia for the precise, though largely assumed and unspoken, purpose of foreclosing on that peril. Besides, people said she was crazy...The woman at Columbia was not demanding to be a participant in an unethical network of distribution: she was not demanding a place within capital, a piece of the pie (the demand for her sofa notwithstanding). Rather, she was articulating a triangulation between two things. On the one hand was the loss of her body, the very dereliction of her corporeal integrity...On the other was the corporeal integrity that, once ripped from her body, fortified and extended the corporeal integrity of everyone else on the street. She gave birth to the commodity and to the Human, yet she had neither subjectivity nor a sofa to show for it. In her eyes, the world—not its myriad discriminatory practices, but the world itself—was unethical. And yet the world passes by her without the slightest inclination to stop and disabuse her of her claim. Instead, it calls her 'crazy'."

- See Wilderson's Red, White & Black, pp. 247-284, for a critique of Hardt & Negri's notion of the withering of civil society.

- See Wilderson's essay, "The Black Liberation Army and

the Paradox of Political Engagement," Ill-Will Editions, p. 26, in which he

notes:

Violence, [Allen] Feldman argues [in Formations of Violence: The Narrative of the Body and Political Terror in Northern Ireland, University of Chicago Press, 1991] begets its own semiotic structure, it is not the product of a (non-violent) semiotic arrangement; in other words, it is not an effect of ideological imposition. He argues that the postindustrial context of economic relations, otherwise known as globalization, has subsumed all of civil society by the command modality of capital. «https://goo.gl/siLIMT»

- Jared Sexton's Keynote Address at the "Terror and the Inhuman" Conference, «https://vimeo.com/52199779». Sexton is drawing on Omar Ricks's "Editor's Commentary: On Violence" «http://thefeministwire.com/2012/10/editors-commentary-on-violence/». Also see Sexton's essay entitled, "Unbearable Blackness", Cultural Critique, No. 90, University of Minnesota Press, Spring 2015, pp. 163-64, wherein he elaborates Ricks' question.

- James Baldwin, The Evidence of Things Not Seen (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1985). In this, his final work, Baldwin examines the peculiar hauntings in the law as it applied to the Atlanta child murders that spanned from 1979-1981, and how the case brings to bear some harsh realities about the relation between American "justice" and black people and their children. Baldwin recounts the case narratively and comprehensively, and opens a space for us to really consider how jurisprudential violence haunts the law. It presciently honors Saidiya Hartman's concern about the reproduction of violence against black flesh, which she elaborates in Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery and Self-Making in Nineteenth Century America, Oxford University Press, 1997, by asserting the ways in which the recounting of such violence actually recreates it. In rendering his analysis of the Atlanta Child Murders and how Wayne Williams was "tried" and convicted by the legal system—which usually presupposes that the "right to a fair trial" has been carried out—Baldwin focuses on what is unseen in the process—the "ghosts in the machine" and as such, analytically laments, rather than recreates, the spectacle of the trial. In short, he poses a question of the travesty of the law, and denies the pleasure of the outcome.