Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge

Northern Hieroglyphics: Nomadic Blackness and Spatial Literacy

Dalton Anthony Jones

Bowling Green State University

PDF

PDF

All Images by Dalton Anthony Jones

M-U-L

I am sitting in the backseat of a Van Gogh blue Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme, thin but healthy. A guy who calls himself "Mohawk John" is behind the wheel. His orange spikes touch the roof, testifying, one hopes, to a commitment to something deeper than just a nickname. He is a friend of a friend of a friend of mine. Like so many of the white youth out in search of freedom that I have encountered since going ABD and hitting the road, he is reckless, eager, and his feet are made of lead. Leaving Chicago we skirt Lake Michigan as the sun begins to set. Gary, Indiana, sullen and complacent, is fading in the rearview mirror and out here on I-65 the battered face of North America is on full display. As we make our way through the rust belt, we drive by literally miles of stark, rugged, industrial complexes: sprawling maternity wards for the crap that shakes the axels of our car as I look out upon the decrepit landscape. A seemingly endless caravan of eighteen-wheelers, pregnant with commodities, rumbles past my window.

There is an almost admirable potency in this tableau. As night falls it lingers over the skyline like a fairy tale and suddenly the brutal poetry of America is captured in an instant. The sun's light bleeds against the long thin line of the stannic horizon and then disappears before our eyes. Just like that, twilight is gone. Devoured. An homage to modernity, the view is haunting: a maze of man made wilderness that appears to be as immortal and grandiose as the Acer saccharinum, Fagus grandifolia and Quercus alba must have seemed to the Algonquin speaking tribes and French traders who negotiated this land for centuries before a steady stream of colonial-settler migrants laid it to waste. One can feel the weight of history and the vast power of the earth that still resides beneath these twisted, deformed feats of engineering. Claws and rivets. Conveyer belts. Metal beam branches. Hanging wire vines and the red eyes blinking in the shadows of these massive structures: we are passing through a skeletal forest of steel and iron. Never has such a desolate scene looked so vibrant, so manifestly alive. But it has never been clearer to me just how fragile and fleeting this panorama actually is. A bag of seeds will restore those wooden monuments of yesterday while the promise of this habitat is already on the run. Following the 86th longitude at least, one can see that it is about to become a memory, a wound to be healed—a scar, like the ones that mark my flesh, never to be forgotten.

A girl with deep henna hair and tattoos who calls herself Jen-Jen is laying across the front passenger seat, her head in the Mohawk's lap with one leg stretched out across the dashboard. Her IPhone, wired through the cigarette lighter, is playing a mix of Rancid, NOFX, Dylan and the Red Hot Chili Peppers. They are the post-Cobain generation, feeding on the carrion of a not-so-distant past, on the flesh of a beast whose heartbeat still echoes loudly, incessantly, in our ears. They are, I mean to say, as amerikkkan as Bonnie and Clyde, simple folk just waiting for their chance to strike, two natural born killers who are as at home in this real estate as Mickey and Mallory Knox. With them, I keep a certain distance, a part of myself hidden, and I extend to them the respect they have earned even if it is not the respect they deserve.

The steady rush of diesel exhaust and cigarette smoke makes my eyes water. Winston ashes blow in my face. An aloe plant pricks me in the arm and forces me to pay attention to how I sit. An empty beer can rocks from side to side at my feet, keeping time with the sonic road-kill that fills the air. I squint, bite my tongue and ask them for a light. I am grateful for the ride, sincerely, but I wish they'd turn the music down. They need new speakers.

As a vagabond—albeit a rather privileged one as the ancient legacy of vagrant wandering goes—I have learned to listen closely to the ways that Humans mark and measure the boundaries of the spaces they inhabit. The uneasy history of nomadic blackness under the wide-open skies of North America, that curious symbol of global emancipation, has prepared me well for this task. First as émigré, then as captive, then as a fugitive regarding with prudence every step it takes along the lines of flight to the four cardinal points of the world and beyond, the black subject, never grounded, always on the run, is accustomed to navigating the enigmatic line between text and subtext, between the terrain and the subterranean. Moving across this tarnished landscape, evidence of the full enclosure of the commons is everywhere and everywhere it conspires to make me understand, with the barbaric reflexivity of commonsense, that I am subordinated to the effect of a cause that long preceded me. Outside my window a portrait of a land born in violence, nurtured in violence, and sustained in violence passes before my eyes. There is no sign of sovereign space for me to call my home, no autonomous zone left for me to suture myself on to, no under-the-commons to use as an escape hatch and no over-the-commons to float away on into the future in a phantasmagorical quest for "we." To believe this is to misapprehend the depth of a wound that has been inflicted on a world struggling to preserve its air, its water, the fertility of its land, the food it eats. My body stands in austere relief against the outlines of a merciless ecosystem. I am a hieroglyphic, illuminating with my presence an entire ecology of suffering and paranoia, exposing with my mobility the stuttering cruelty of an unfulfilled mission that lies dormant here, active there, hiding in the nomenclature of our culture like a felon crouching in fear of being found, of being talked about too closely, of being driven to the surface of things with words. Like the wilting world on fire, I, not it, am the mark of difference and the figure of repetition: the persistent (disa)vowel that gives the multitude of consonants around me their signification, a body that makes complete a transcript with far too many rogues for one story to contain.

Running from the sun only to reach it in time for tomorrow, we navigate our way around a string of black holes with gravitational fields that are far more conductive than my one black body, a concentration of holes like me that deform time and space, warping the narrative of the American dream, drawing it into a vacuum that transforms it into a delirious hallucination that is as devoid of light as an abandoned Detroit street at night. One moment, we are a stone's throw from a city so hard and volatile it is named after a rock that makes fire, a city poisoning its children by the tens of thousands out of boredom and bureaucratic necessity, quenching their tiny thirst with a neurotoxic element known to create permanent brain damage in vertebrates since the Shang Dynasty of 1,500 BC. The next moment we barrel past the refugee camps of Toledo and Cleveland, following the outlines of a lake so eerie it blossoms with thick-green algae every summer as the result of a phosphorous runoff that produces a liquid scum so noxious you cannot drink or even bath in it: cutting off the water supply to half a million people being just another of the "negative externalities" of factory farming and genetic modification. We see towns overshadowed by nuclear power plants, steaming concrete cylinders drawn tightly at the waist like Victorian women bound in corsets coughing, trying to breath, looming twin towers leaking a steady stream of tritium waste into the nature sanctuaries and public swimming holes that surround it. The magnetic pull into blackness along this drive is more harrowing than any narrative of nation or state can possibly fend off, too irrational to contain or sustain. I see a withering geography that is, as Katherine McKittrick describes it so well, as much demonic ground as fecund soil or safe haven for life.

Precarity in the face of a predator as exotic and insufferable as Man forces one to hear with the eyes and see with the ears; to touch with the mouth and taste through the very pores of the skin. Evolution demands sensitivity to detail. More than a theoretical meditation on the "symbolism of architectural forms" or even an aesthetic rumination on the organic relationship between a structure and its social function, spatial literacy is a survival mechanism, an act of self-preservation more urgent for the endangered species than for those living at the top of the food chain. In the hands of cartography, the science of land and measurement, of record keeping and permanence, of engineering, of bridges and dams, of prisons and zoos and confinement, of surveillance and cameras and drones, spatial awareness is a weapon of social control: A tool of domination. Form and function are necessary correlates nowhere more so than in the face of extinction, l'art pour l'art being as useless as the wings of the Dodo Bird. Even the illicit "production of space," the discursive reclamation of the walls that confine us, is rendered fleeting, restricted and abstract under the conditions of late capital and global governance we encounter; under the morphing and intensifying expressions of modernity we are forced to navigate. We are fatally intimate with these highways and fences after all. We know what they are meant for and how they came to be. We know their wages and we know without being told that the backroads and shortcuts are no longer a viable option. So I listen carefully to what the surface of things has to say and I heed the advice I receive accordingly. We are always in proximity to danger and the land I am moving through is closing in around us like a noose drawing tighter and tighter with each passing day.

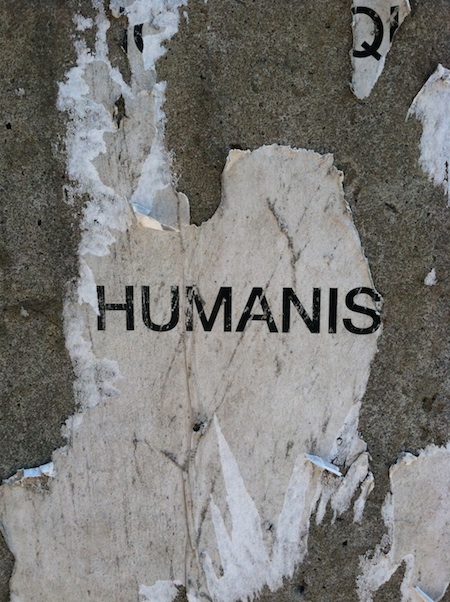

Words and signs are a dwelling, a zone of domesticity, an instrument of coherence. Words and signs are a tool of domination, a menace. Words and signs are a technology of salvation and deliverance. But above all, whether nuisance, threat, or sanctuary, words and signs are a navigational device. Words and signs are unstable, shifting in meaning only because they are how we move, and when it comes to articulation we are scavengers far more concerned with subsistence than high philosophy. The law of natural selection holds as true for the plasticity of language and the decorum of grammar as it does for the negotiation of space. Territorial animals, humans make their presence known even in their absence and this artery through the heart of the nation is no exception to the rule. Along the sound barriers, against the sides of abandoned railroad sheds, clinging to the billboards and overpasses, we are followed and preceded by illicit lines. An elaborate semaphore stretches out before us, guiding our way just as surely as Daniel Boone's vulgar hatchet once marked the trees, steering modernity with its voracious appetite and relentless insistence on "I" across the hills and hollers of Ohio and Appalachia in the first place. The voices of those with a synthetic attachment to this land mingle with the wayfarers like myself who are just trying to keep low as they make their way forward to someplace else. Our conversation is inscribed on the surroundings with chaotic precision. Letters without words, words without sentences; a montage of characters suspended without clear-cut frames of reference. E-L-K....S-T-P....R-K-Sha....D-V-S, and the tag that emerges above the others with dogged regularity, M-U-L.

I recognize something of myself in the liminal highway literature I pass. Graffiti, wall writing, tags, the errant lines that twist and bend the precision of the surveyor's chainage, are a scripture that belongs in the hands of the displaced and the h(a)unted. Like jazz, a black sound emerging from the contradictions and barbarities of a slave democracy, our-selves, our identities, our desires and aspirations, our wounds and our scars, walk across the plane of language with an improvised disregard for the rules of conduct. As the universal "disappearing subject" of discourse, I am the inability to locate textual authority. I am the measure and value of goods on the market: a black hole on the white face of modernity, my body is the demystification of the mystification of value. If the struggle to establish a coherent position within a constantly shifting system of signs is one of the great political struggles of our age, we are, thanks in no small part to the lessons learned from the discursive interventions of the black vernacular and its body, becoming quite effective at performing this radical maneuver. Letter-by-letter, syllable-by-syllable, word-by-word, image-by-image, a new language, embryonic and inchoate, is defacing the value accumulated in the creaky edifice that is crumbling around us even as it continues to churn out and police its signifiers. The art of spatial literacy— the ability to read one's environs in order to decode and disrupt the center of discourse—is the lingua franca of blackness. The disintegration of language, the transcendence of its limitations and the acknowledgement of its betrayals, has led to a fluency with the "multiplication of modes of writing" that fill this littered, lettered landscape.

If all of this sounds somewhat familiar, it is. Strategic illiteracy has been at the core of any modernist literary ambition with integrity ever since its genesis in the slave trade's brutal disarticulations of the black subject-in-space and the clearing of the frontier of its indigenous savages. The effacement of colonized space is more than just the revenge of the speech act upon the imposed codification of the written word: it is, at its core, an in-human act and, defiling such a subject position, necessarily a revolutionary one.

Roland Barthes spent the last three decades of his life trying to divine the revolution and its saboteurs in boxes of detergent, string-net bags of pasta and Japanese travel guides. Ironically, if Afro-pessimism affirms the right to assert the living presence of the past, a past it has not just been robbed of but a form of social death it has been refused to mourn and encouraged to forget, escaping the "burden" of the past has been one of the exemplary missions of European high philosophy. For Barthes, the father of semiotics and a guiding force in the move away from the stability of order and into the magical land of poststructuralism, history in its entirety stood before us unified in language. All of the dramas of value and exchange were bound and tied by the grammatical inheritance of the word. To be free of the constraints of an authoritarian past meant to be free not only of its narrative, the ideology and bureaucratic tongue that legally and ethically sanctioned the form and order of hierarchy, but to demolish the very structure of its articulation. For him, the purview of "degree zero" therefore meant pushing the linguistic inheritance of old France beyond the materiality of the written word and into a new event horizon, creating a new grammar that spilled over into the abstraction of visuality. Barthes sought his escape by turning to a set of visual codes, elaborating a system that, he argued, was capable of operating beyond the creative constraints of a stale, oppressive, European formalism. He believed passionately that the protocols of literacy imposed a limited psychic frontier for the free sovereign European subject, a nightmare ontology that could only be surpassed (or suppressed) through the creation of a non-compliant, unbound mode of articulation.

But this is where Barthes veered astray and missed the mark. He failed to recognize, or was unable to read the signs of the times he was living in well enough to know that literacy is more than a symbolic act; it is a full out contact activity with dire consequences. Literacy demands full embodiment. The war in Algeria was more than a media spectacle: it was, as he averred but evidently could not grasp, a lethal encounter between men with bullets over territory. In a version of hear no evil, see no evil while one hears and sees evil, Barthes advocated for an "insurrectionary literature" lifted from the convention of the page, without the enforced boundary of authorial intent, a renunciation that was configured as an act of rebellion, an uprising against structure whose modus operandi was respite from the burden of Francophone sterility, hierarchy, and, yes, guilt. A "neutral" writing Barthes tells us, one premised on the democracy of articulation, would emerge from the quest to realize "a mode of writing which might at last achieve innocence."

The democracy of articulation...the burden of the past...a neutral writing...the attainment of innocence. Although a perverse fulfillment of Barthes' dream, the broken dialect spoken along this corridor might just represent the last stand of the Enlightenment project for which France is at least partly to blame. It is a grammar of dispossession that poses an insolent challenge to the letter of the law and the ethical cohesion spelled out by liberal Humanism's covenant between power and those it purports to govern. One thing is for sure, the authors of this nomadic literature are not waiting for the sanction of high theory to speak. They do not need to be reminded that the structure of grammar is the pawn of authority or that their voices are locked within a prison-house of language. These negro highway scribes in spirit, speaking in a language that blackness speaks fluently, are trying to liberate the sign from the clutches of the written word, reveling in the act of defacement and recreation, and although it may be a futile task they are, at the very least, demolishing any pretense of a formal line between signifier and signified, about what the past means and what the present is. But blackness is a dark place, full of holey ghosts, and few choose to risk that journey of their own accord.

The town we are passing through now has its back turned as if it is sleeping and beyond the highway divide I see no one, not a soul. The houses, some of them little more than shacks with crumbling foundations, look empty. The yards naked aside from some children's toys: a plastic slide faded from the rain discarded behind a mustard yellow trailer-home...images of an Easter Bunny being used to patch a small hole in the wall. A snowmobile arching on a snowless mound. Rusting cars rotting in the bushes. Signs of alcohol and poverty. Most of the roadside markings I take in appear crude and irrational. The colors are sparse and fading. Dull and unkempt. They catch the eye but are overshadowed by the black and white lines thrown against the surface of the passing architecture with such evident haste: they amount to a restless affidavit, a perfect indictment against the neurosis and alienation of a New World order that is finally coming home to roost.

By the time the sun rises we will have entered the land of the six nations, the ancestral territory of the Iroquois. So far, I have been speaking with my cowboy companions in rather sparse sentences. Not unfriendly, mind you, but rather short and to the point. In truth, this is all they have made room for, their passion for life and one another issuing forth in a steady stream of consciousness, their words binding them together as they cover the land with their wheels. It is a suturing of whiteness that makes me mute in its presence. They are bonding with one another and asserting their sense of freedom in this republic whose domain has changed in the last five hours from urban blight to flat, greasy plains, to the first gentle signs of rolling mountains and summertime retreats. When I do speak it is mostly to offer a general assent to their own affirmations delivered as interrogatives, the form of our dialogue already implying the structure of my response. It is less a script I am following than an improvisation with loose rules that have ill-defined consequences for those who violate them. It is a map they are making for me to follow, a grid with the choice of more than one possible route to reach the same destination. And playing the part, I have dutifully consented to be led, needing, as I do, this ride. We pick our battles wisely, and, anyway, as spectatorship goes, to me the land outside, however dark the night, is mythic. I use my voice to deflect and when my truth begins to stray into the public domain it is generally in the form of allusion and multiplying entendres I intend for them to interpret as the expression of eccentricity, cool, and not of an apostate to a cause they have managed to implicate me in by sheer proximity and without my consent. There is a war on terror, after all, and it began right outside this window.

The easy slide into complicity happens with the snap of the fingers, when you are paying attention to something else, something like safety or protecting your dignity by staying calm. But speed cannot hide the fact that this was, and, of course still rightfully is by any measure of justice, indigenous land that I am violating and I have approached it once again under the escort and under the guise of the colonial-settler. A part of it yet so, so far removed that it is hard to feel remorse. But I tilled and seeded this soiled earth. I cracked and ate the stolen corn. I cut and carried the tortured timber and drove the fence posts into the earth. And even if I did the Gandy Dance to pass the time, it was I who hammered the rail spikes into the tracks that cut red blood paths across the country, sealing our fates together forever. If I killed their buffalo and helped set the prairies ablaze, what can I tell them today? My hands were tied. There is no bureau of African American Affairs, no territorial sovereignty for me to fight for. I have no casinos to bet my future on and there is certainly no reservation about my place in relation to the order of things as they presently stand.

"[T]he nomad has no points, paths or land," writes Deleuze or Guattari, we are never quite sure who is who and which is which, "even though he does by all appearances[.]" A perfect description of my blackness I would say. No wonder there is such a dearth of accomplices for me to turn to, including among my kin.

If the nomad can be called the Deterritorialized par excellence, it is precisely because there is no reterritorialization afterwards as with the migrant, or upon something else as with the sedentary (the sedentary's relation with the earth is mediatized by something else, a property regime, a State apparatus...). With the nomad, on the contrary, it is deterritorialization that constitutes the relation to the earth, to such a degree that the nomad reterritorializes on deterritorialization itself.

It is a painful pill to swallow, a hard and lonely way to be a revolutionary in this world. For nomadic blackness, the violently deracinated subject, the constant mobility of deterritorialization is a haunting spectre, an unstill quest, an exercise in solipsism, not a respite from the troubled failures and ugly defeats of the soil. An accurate description, no doubt, but to reterritorialize deterritorialization is, for the black subject, to resubmit to the wound of captivity in an endless cycle of assent, a nightmare of re-flagellation. Deterritorialization is not a space of liberation, at least not when it is coerced; it is a space already inhabited by the captor, colonized by the colonizer, capitalized by the capitalist. Such contradictions produce violent antagonisms in terms of the black subject's right to, first, try to maintain its center of gravity in and through the world by affirming the right to self-determination and autonomous community building, and, second, and more to the point, produce a grievance by articulating an "ethics of the real" when this ambition is dislodged. It is the right to protest and adequately defend oneself against the state of Objective Vertigo articulated by Frank Wilderson, "the sensation that one is not simply spinning in an otherwise stable environment, [but] that one's environment is perpetually unhinged stem[ing] from a relationship to violence that cannot be analogized." The domesticated subject of Domestication. The oppressed subject of Oppression. The violated subject of Violation. These are heady claims, but a fair review of history demonstrates that blackness is the original (in terms of modernity at least) governed subject of all these things, all these processes. In this regard, and this regard only, can we say that "[t]he black body," as Dionne Brand has put it, ought to be understood as "a domesticated space as much as it is a wild space." To occupy this body, she tells us, is to live a life that is spoken, "in the blunt language of brutality," to be ordered by a vocabulary where "even beauty is brutal." The reterritorialization of Nomadic blackness is a result of the gravitational pull of a discursive and territorial black hole whose center is vacated: and nature, or at least we are taught, abhors a vacuum.

How, then, does one develop a working genealogy of a conundrum such as Afro-pessimism? Where does one begin? How is it possible to chart the history of something as polymorphous, as generative of and yet so abjectly banished from the life of Western modernity as the phenomenon of blackness-as-negation and negation-as-blackness? How does one narrate a story whose most poignant expressions have never been made with the written word or debated forthrightly in the public transcripts of civil society? How does one develop a functional vocabulary of silence? How does one paint a portrait of the unseen? And, most gravely perhaps, how does one do this crucial work while remaining sane in the face of a million commonplace and pitiless deferrals?

The first challenge one confronts when trying to develop a theory and practice of black study is the problem of scale. That is, accepting the daunting task of conveying the sheer magnitude, the confounding depth and breadth of the topic at hand. Elaborating the slave's capture and subordination, establishing the relationship between the violence entailed by this process and the most essential and seemingly inessential formations of the modern (on the one hand, the nation, the state, civil society, the regime of value and its accumulated surplus and so forth; on the other, the minute protocols that organize our affiliations and disaffiliations with these meta-dispositifs of power), is itself enough to test the most stable psychology and blackness, we must remember, is born just a little bit crazy. But elaborate them we must, for without this effort all subsequent theorizations of blackness fail. Lindon Barrett's posthumous and tragically incomplete masterpiece, Racial Blackness and the (Dis)continuities of Western Modernity, serves as a case-point for the almost maniacal lengths a brilliant mind such as his must go through in order to demonstrate with precision (for anything less than precision will be dismissed outright on a technicality) the emergent circumstances of racial blackness, to show the centrality of trans-Atlantic plantation slavery to this formation, to catalogue the means by which slavery was a constituent element in the development of capitalism and is thus a constituent element of the contemporary global distribution of wealth and European territorial hegemony, of tracing the historical transition away from European feudal and monarchical forms of consolidated power to the more elusive, flexible forms of capitalist authority we live under today, to call attention to the consequent unstable formation of the human as a normative subject, to assemble an encyclopedic catalogue of the philosophers, historians, psychoanalysts, revolutionary anti-colonialists and social scientists of the more tame type who buttress these truths in order to show how and why we can and must see the extraction, consolidation, and distribution of resources in the creation of the Atlantic economies as not just foundational to but an ongoing process in the formation of the modern world, to emphasize, finally, the relation between the materiality of power and the "discursive grammar" by which subjects are composed and imagined, and all of this as prelude to say something else, something as simple as "I am" and "I am here." Reading Barrett's exhaustive résumé one can feel the frenetic energy expended upon the project and the almost perceptible slide into madness as he attempts to elaborate the elaborated, to prove the proven, to speak what has already been spoken, to be heard in a world where blackness lives in and is defined as vacuum: A living black hole pockmarking the face of modernity.

Capitalism and Schizophrenia, Civilization and Its Discontents, Madness and Civilization: all of the classic exegeses on mental illness and modernity express the dementia of blackness in its stable form. To be black, is to be mad. To be sane in a world of repetitive violence against one's body and soul is to be mad. Blackness is an unstable delirium that sucks the very light out of Enlightenment. If Afro-pessimist thought forces us to make an accounting of the past, its imperative, its impetus for being, the persistence of its assertion as a destabilizing injunction, is driven by decidedly contemporary concerns. It is the effort to make an honest accounting of the question, "where does my body stand in relation to my flesh and how can they both, one without sacrificing the other, find a stable place to stand in this world or, in the meantime, how can I at least find a way to speak the contradiction and violence of that displacement?" It assumes the task of answering this question by delving into the past not for the sake of melancholy, the right to sing the blues or wallow in self-pity, but in order to elaborate the mechanics of a wound that still festers. It is an exhaustive project that demands willpower and invites sanction at every step. It entails not cutting a truce between the past and the present, not accepting a plea-bargain that leaves our accumulated grievances and the perpetual expendability of our lives off of the negotiating table in exchange for the dubious right to join the legions of alienated and exploited citizens struggling to find coherence in an insane and abusive new world order that has evolved, seamlessly and coercively, from the old. To hazard the consequences of not raising the white flag is an act of courage. But one look out of the window at the America I am traversing across tells me that I do not want to join the rank and file I see. And with that decision, for better or worse, begins a struggle that cannot rely on the power of affirmation alone. It demands that one produce a string of negations as persistent and unrelenting as the steady repetition of deportations that promote one's exile, and it requires one to challenge, ruthlessly, the unethical stability and indefensible centrism that has been the operational status quo of modernity since its inception.

For this reason, Jared Sexton, who provides a concise overview of the objections mounted against Afro-pessimism, asserts, following Wilderson, that Afro-pessimism is as much a structural position as a school of thought or collection of ideological dogmas. (Sexton, Afro-Pessimism: The Unclear Word, 9) Rather, it is a (dis)position of embodiment that is deployed and asserted at key junctures. While the encounter may not always be willful, it inevitably emerges of its own accord with a predictable yet spontaneous regularity. It disrupts the flow of social discourse, particularly at those moments of convergence between the black body and its "institutional inscription." More than a unified polemic, although it can be this too, Afro-pessimism is an extended meditation upon a set of accumulated negations growing out of the contradictions of Western thought and practice. Sometimes these can be moments of catharsis, appearing as a productive intervention, creating levity and release in unexpected places at unexpected times, but their (re)appearance and (re)iteration occur with such frequency, and always in a mode that replicates the grievance of blackness, that even such affective solidarities become a structural disposition bound by a relation of violence and a posture of negation.

Afro-pessimism is, in other words, first and foremost a political imperative.

If black thought and black being take exception to the authority of the sign, it is for very different reasons than those articulated by Barthes and the main body of poststructuralism. For Afro-pessimism it is that the structure of language, the fluidity and potential creativity of the word, is bound by a systemic shock whose ground zero is not monarchy, feudalism, labor exploitation or the multiple forms of alienation they produce, but the awe and occurrence of a structural violence rooted in captivity and the imposition of social death, the black body as removable, kidnapable, killable, fuckable, and, in an endless variety of ways, unaccounted for in civil society. This is the only way to fully understand the gesture of madness (not just anger, but actual insanity), that appears, say, when Sandra Bland slams her phone on the hood of her car after being stopped for the civil offense of not using a blinker to change lanes or the routine nature of her subsequent death by hanging in a Waller County, Texas jail cell. Every one gets tickets they feel they don't deserve or has a bad day, but here we see how the structure and authority of the word encounters the structure and authority of civil society: how the legacy of social death in one realm, the instability of linguistic structure that Barthes (and Foucault) would call the "death of the author," colludes with the grammar of violence that organizes the state around the black body:

Encinia: I don't know, you seem very really irritated.

Bland: I am. I really am. I feel like it's crap what I'm getting a ticket for. I was getting out of your way. You were speeding up, tailing me, so I move over and you stop me. So yeah, I am a little irritated, but that doesn't stop you from giving me a ticket, so [inaudible] ticket.

Encinia: Are you done?

Bland: You asked me what was wrong, now I told you.

Encinia: Step out of the car.

Bland: You do not have the right. You do not have the right to do this.

Encinia: I do have the right, now step out or I will remove you.

Bland: I refuse to talk to you other than to identify myself. [crosstalk] I am getting removed for a failure to signal?

Encinia: Step out or I will remove you. I'm giving you a lawful order.

Get out of the car now or I'm going to remove you.

Bland: And I'm calling my lawyer.

Encinia: I'm going to yank you out of here. (Reaches inside the car.)

The poststructuralist attempt to exploit the instability of the word in order to dodge the authority of structure was meant to free the purported "sovereign individual" from the clutches of a hierarchy rooted in conquest and capital, a heritage that was, by the 1950s, being challenged as morally and militarily indefensible. If we are "franc" about it, we will note that the critique of French national and colonial heritage lodged by Barthes, Foucault, Derrida, Baudrillard, and, yes, although always marching to the beat of his own rhythm, Gilles Deleuze, was due in no small measure to the revolutionary demands of colonized black and brown people for self-determination and, short of this, citizenship and administrative equality: the battle of Dien Bien Phu of 1954, the Algerian war of independence from 1954—1962, and the advent of the civil rights movement in the United States, being just a few examples of the anti-colonial resistance that ran concurrently with the most productive and innovative work of European philosophy.

Barthes and his cadre of colonial intellectuals may have even recognized in their aspiration that they were inviting the dispossession of an authoritative voice of whiteness that they could not escape any more than the black subject could bypass her exclusion from the discursive center. But I am fairly sure they did not recognize what the consequences of their disavowal of displacement might be. We might categorize Fred Moten's In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition, one of the most groundbreaking texts in the canon of black thought from the past decade and a half, as a work whose two-fold objective is, first, to deconstruct deconstruction, critiquing the deft maneuvers of European theory to salvage a privileged center and, second, to offer an alternative analysis of poststructuralist and postmodernist theory from the purview of the black voice, in particular its ability to exploit the interstices and breaks of articulation, the in-between spaces made famous by Homi Bhabha whose argument Moten extends, to its radical advantage. Deep into this project, Moten, in a rather brief but dazzling exposition of Barthes, deconstructs the semiotician's effort to construct a new theory of the visual sign by illustrating how his maneuvers ultimately amounted to the conceit of an "egocentric particularity" in which "a critique of the suppression of the determining weight of history is left behind for a stance that is nothing if not ahistorical." It is on Moten's second thesis, the possibility of a zone of radical black transformation within the structural (linguistic, symbolic and empirical) grammar of the empire of signs (and bodies) that he and the Afro-pessimists have engaged in what is arguably one of the most eloquent, comprehensive, magical, rational, civil, contentious, and rigorous dialogues that Western theory has ever produced. David Marriott, one of the key participants in this generative exchange, extends this debate within Afro-pessimism with his contribution to this special issue. Offering a reading of Moten's request that we approach Frantz Fanon as if "for the first time" in order to salvage an optimistic reading of the revolutionary Martiniquais, Algerian philosopher/psychologist's writing, Marriott pinpoints the anxieties of nomadic blackness and its repetition and deferral:

if Fanon hears what Moten does not hear (in terms of his reading of the case), this is because Moten can only affirm blackness as affirmation, not because it escapes pathology, but because blackness is experienced only as the activity of escape, but one which never escapes the ontology of such production. It follows that blackness cannot escape its own fugitivity; its constitutive moment is traversal (or, what constitutes it is its force of subversion with regard to the pathological classifications of blackness). (Marriott, Judging Fanon, 3)

Afro-pessimism begins with the general recognition of the organizing capacity of violence. It traces the contemporary conundrum of blackness back to its deployment as a mechanism of African captivity and slave incarceration and the centrality of this instance to the creation of the so-called New World. What is at stake, then, is the question of continuity. That is to say, following the groundbreaking work of Hortense Spillers, that if my body does not (yet) bare the scars of the trans-Atlantic and plantation slave experiences—the whip-marks across my back, the blisters on my feet and fingers from toiling, the rope burns around my elongated neck—these wounds live on in the legacy of my flesh. It is Spillers who, emerging out of the radical context of the black women's rights movement, has shown us with the most lucid clarity how the ensemble of violent structures that arranged the body of the black slave comprises a continuum of trauma, a "human sequence written in blood, [that] represents for its African and indigenous peoples a scene of actual mutilation, dismemberment, and exile." For Spillers, the distinction between body and flesh is an expression of the continuity of a suffering that goes hand-in-hand with the will to live, to survive with integrity, with what she, offering a direct challenge or corrective to the ambitions of modernist discourses that long for and believe in a degree zero of articulation, calls "that zero degree of social conceptualization that does not escape concealment under the brush of discourse or the reflexes of iconography."

There is a wall you cannot see that runs from English Bay and traces the length of the 49th longitude for over one thousand five hundred miles before dropping south into the waters of Lake Superiors and Huron. It squeezes through the occupied territory of the Aamjiwnaang Nation, a people living on land that is so toxic from the largest concentration of oil refineries in Canada it has been nicknamed "Chemical Valley." The wall you cannot see cuts like a knife between the cities of Detroit and Windsor then rises up through the shipping lanes of Lake Erie and Ontario. It follows the St. Lawrence River, turning abruptly east, snaking its way around and through valleys, forests and wetlands until falling, at last, into the Passamaquoddy Bay, the traditional fishing grounds that divide the United States mainland from Blacks Harbor and Nova Scotia, Canadian territories where tens of thousands of dark skinned refugees came looking for shelter from the terrors of the plantation slave economy and the retribution of Europe's anti-colonial warriors.

Morning has now officially broken on upstate New York, and in about an hour we will be in Syracuse, where I will catch the next Greyhound bus to Montreal.

Walls are many things.

A wall is a construct.

A wall is a battleground.

A wall is a sanctuary.

A wall is a statement.

A wall is a threat.

A wall is a tool.

A wall is a border, a frontier.

A wall is the necessary prerequisite for the grapheme. The written word. Walls are what transition space into territories. A wall is something that I have always felt up against, in the "up against the wall motherfucker" sense. But walls, like the letters and words that mark them, are also my friend, an armor and a tool of navigation I have been wearing for the last fourteen hours in the backseat of a Van Gogh blue Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme. It is through the markings on public and private space that I learn to read behind the limited vocabulary of direct discourse with my body, whose literalness assaults my eyes and the eyes of the world. To see behind the said of the word on the page of the books that I see and read and beyond the said on the lips of the bodies of those I meet, touch, and hear. It is by embodying this space that I learn to piece together a language of collective sovereignty whose lines are fluid enough to withstand the imposition of silence and transgress the privatization of the word.

Communication is a spatial act; there is a movement of representation through time and space. Moving through this territory, my body becomes an extension of articulation's unpredictable fluidity; the critical "I" becomes the critical "eye," a participant in a "nomad grammatology," a practice of reading that, Deleuze asserts, is "traversed by a movement that comes from without, that does not begin on the page (nor the preceding pages), that is not bounded by the frame of the book." I am a literary nomad reading cultural texts that are "entirely different from the imaginary movement of representation or the abstract movement of concepts that habitually take place among words and within the mind of the reader." This nomad's language resides outside of the sanctioned authority of the organizational state precisely because it does not remain rooted to and within a territory. In his introduction to A Thousand Plateaus, Brian Massumi, noting that the State desires a sedentary, fixed literacy, tells us that "history has never comprehended nomadism, the book has never comprehended the outside." Although nomadic blackness may travel the surface of a territory, it may be bound by fascist investments but it does not honor such claims to authority, it submits to them out of a concern for survival.

Time and space bend differently for an outsider than they do for the local subject. A newcomer experiences a disorientation that can bring her curiously in tune with the curvature of her environment—it is the sensation of seeing the world as through a microscope and a telescope at once. A journeyman, a traveler, a nomad becomes a cartographer and draws coordinates between some unlikely points of reference. In the midst of confusion there is a sense of clarity, a sharpness and disorientation to the three dimensions of space. This second sight is the view of the vulnerable horizon that lurks in the colonial-settler gaze; in the perverse desire that resides in the boxer shorts of the tourist; in the compression of need found in the migrant hand in search of labor, in the pulse of a hungry refugee's beating heart. There is nothing neutral about my black gaze. My blackness and poverty, my eyes and ears, my body, are still the mobile subject of capital, the ever present, contested "I" of history that needs to be harnessed, contained and, if need be, captured and neutralized.

On the walls of the America I have been travelling through, letters and words are everywhere and everywhere they have fragmented and scattered. In a country, the United States, whose first principle is ostensibly freedom of speech, occupying the space within which to articulate is remarkably elusive. The commons is a fantasy and individualism is kept quiet behind closed doors. Aside from the adolescent vandal who spray paints over a stop sign, erases the exit marker or disfigures with a mustache the company billboard spokeswoman, c/overt political speech is rare in the Anglo territories. Above the Rio Grande and below the Great Lakes, there are virtually no stealth denunciations of politicians; fat cat capitalists move about with ease, the ever-expanding regimes of the police state who uphold a social contract no one can remember signing their names to anymore go about their business undisturbed. Corporations are not attacked in the night on the walls of our domain. Radical propaganda, such as it exists, is sterile, our dissent always already rendered moot; our words and gestures as enclosed and sanctioned by authority as art and style ever were under a fascist regime, a sign, for sure, of what we have become. And the land. Only the names of rivers, valleys and towns vaguely remind us of what came before these dreams of innocence. Nobody, least of all the colonial-settler, speaks of decolonization anymore.

In the front seat, my travelling companions and I prepare to say goodbye. They have boxes and a plastic drainer stuffed with cups, plates and potholders. An old table they salvaged along the way is crammed behind Mohawk John's seat. I can't hear everything Jen Jen says, but I can see her hands orchestrating a narrative and know she is talking about how much she and he are in love and how they met. As far as I can make out, they are planning to shack up somewhere south of here. He has a job working for her uncle cutting trees, or maybe it is lawns. I can tell that Mohawk is annoyed every time a car is going faster than we are. He glances over his shoulder and grips the steering wheel too tightly as he looks for an opportunity to dodge our lane. Every now and then Jen Jen accents a point by leaning up over the seat to show me the sincerity in her eyes. It is so genuine that she almost has me convinced that their future looks bright, but I cannot escape the feeling that they are an accident waiting to happen: a newspaper clipping if they are lucky. Passing around a can of beer and rolling a joint, they defy the law with that casual ease so common among America's white youth and I am aware of how much my destiny is tied to theirs against my will. They will have money for a roof, domestic beer, some weed, car insurance and, soon, a flat screen television, I am sure. At 23 this is independence. At 45, it's a rut. Looking up at an overpass I notice what I have been looking for in the back of my mind. In bright and clear letters is a simple, ornate phrase: Made U Look.

The constitution was written with a quill pen, but for the time being the three of us are going eighty-five on ninety, travelling more than six hundred miles across old paved Indian trails.

This is the country I am about to leave behind.

Notes

- See, Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Right To Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011); Simone Browne, "Race and Surveillance." Routledge Handbook of Surveillance Studies. Ed., Kirstie Ball, Kevin Haggerty and David Lyon (New York: Routledge 2012), pp 72-79.

- McKittrick's thesis leaves open the possibility that this troubled ground is also a hallowed zone, a space of perpetual resistance, reconfiguration and collective rebirth. Speaking of the "corporeal schemas" that have evolved from the black historical experience of "geographic captivity" she notes that: "black subjects challenge how we know and understand geography; by seriously addressing space and place in the everyday, through the site of memory and in theory and text, they also confront sociospatial objectification by offering a different sense of how geography is and might be lived." Katherine McKittrick, Demonic Grounds: Black Women and the Cartographies of Struggle (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006) p 92, 121.

- Horatio Greenough. Form and Function: Remarks on Art, edited by Harold A. Small (Berkeley, Univ. of California Press, 1947). See also Venturi et al, Learning from Las Vegas (Boston: MIT Press, 1977).

- Roland Barthes, Writing Degree Zero, Trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith (New York: Hill and Wang, 1999) p 67.

- Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1980/1987) p 381. Emphasis in original.

- Frank Wilderson III, "The Vengeance of Vertigo: Aphasia and Abjection in the Political Trials of Black Insurgents," in InTensions Journal, Special Issue, "(De)Fatalizing the Present and Creating Radical Alternatives, Special Issue 5 (Fall/Winter 2011), York University.

- Dionne Brand, A Map to the Door of No Return: Notes to Belonging (Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2001) p 35.

- Lindon Barrett, Racial Blackness and the (Dis)continuities of Western Modernity (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2014). Frank Wilderson takes on a similar, albeit abbreviated, task to Barrett's in what is widely considered to be the magnum opus of Afro-pessimism, Red, White & Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms. In the introduction to his work, Wilderson foregrounds his thesis on anti-black violence as a "positioning matrix" for the ontological, libidinal, affective, grammatical and cartographic structure of black social life, and indeed, modern life as such, by rooting it in a detailed elaboration of the formation of European and new world civil society as an outgrowth of an African slave trade that turned "human bodies into sentient flesh." Wilderson, Red, White & Black, p 13-25.

- Michel Foucault, Madness & Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason (New York: Random House, Inc., 1965)

- The general train of this observation, and the term "institutional inscription," is drawn from Jared Sexton's deft reading of the various strains of discord and harmony within black studies as it attempts to deal with the pull between the affirmation of social life and the apparent ontological cul-de-sac of social death: particularly as this tension emerges within the work of Fred Moten. See, Jared Sexton, The Social Life of Social Death: On Afro-Pessimism and Black Optimism, in InTensions Journal, Special Issue, "(De)Fatalizing the Present and Creating Radical Alternatives, Special Issue 5 (Fall/Winter 2011), York University.

- Transcript attained via Global Research: Centre for Research on Globalization, «http://www.globalresearch.ca/full-transcripts-of-sandra-bland-arrest-prove-cops-broke-the-law-and-made-false-arrest/5464990». Accessed March 6, 2016.

- Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press, 2003).

- Hortense Spillers, "Mama's Baby, Papa's Maybe," republished in Black, White and in Color: Essays on American Literature and Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003) p 206. Emphasis added.

- Ibid, 206.

- Ibid, 206.

- Gilles Deleuze, "Nomad Thought," in The New Nietzsche: Contemporary Styles of Interpretation, (Dell Publishing Co., Inc., 1977) p 143.

- Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, "Introduction," Brian Massumi, p 24.

Cite this Article

https://doi.org/10.20415/rhiz/029.e01