Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge

"We're Going To See Blood On Them Next": Beverly Buchanan's Georgia Ruins and Black Negativity

Andy Campbell, Ph.D.

Core Program Critic-In-Residence

(Glassell School of Art / Museum of Fine Arts,

Houston)

PDF

PDF

Can we accept the idea that the richest soil has been tainted—or maybe enriched—by the negative? — William Pope.L

I

Macon, Georgia, early 1980s: Driving past the Booker T. Washington Community Center on Monroe Street in her yellow Volkswagen Beetle, Beverly Buchanan spots three men sitting on her sculpture, Unity Stones. That the men are sitting on Unity Stones instead of looking at it, contemplating it, is not so strange; after all, Buchanan made it clear in interviews with the local press that her intention was for the public to use and sit on the lumpen, black, concrete and granite forms. Rather, it is the character of the men's interaction that gives the artist pause. Seeing the men argue, gesticulating their frustrations to one another, Buchanan thinks to herself: "We're going to see blood on them next" (Waddell, 1985).

Recounted in North Carolina at a 1985 panel discussion dedicated to "contemporary issues for black artists" (which included two founding members of AfriCOBRA), Buchanan's anecdote speaks to the complexities of black artistic production and reception. Not content to simply expect the best of black people, Buchanan also imagines the worst.

That such an incident occurs on a sculpture performatively invoking the reparative value of "unity" via its titling—a value uncoincidentally shared with the democratic project and attendant black imaginary suggested by Booker T. Washington and his politics of gradualism, cemented by virtue of Unity Stones' placement in front of a community center bearing Washington's name—bespeaks Buchanan's knowing engagement with her work as a site for the production of, what I term, a politics of black negativity which can be handily aligned within the rubric of Afro-pessimist thought.

Buchanan concluded her anecdotal reminiscence with: "The piece [Unity Stones] serves as a communal place to sit and talk, and do the other things that we do." It's these "other things" that most concern this essay.

Beverly Buchanan lived and worked in Macon, Georgia for eight years, 1977-1985, and during her stay completed a host of large-scale public projects across the state. I focus my attention on three of these: Ruins and Rituals at the Museum of Arts and Sciences (Macon, GA, 1979) (figure 1); Marsh Ruins located in the Marshes of Glynn State Park (Brunswick, GA, 1981) (figure 2); and Unity Stones (Macon, GA, 1983) (figure 3). Each project is informed by an engagement with the historical and continuing racialized politics of the Southeast, and articulates a formal and material concern with the kind of black negativity proposed by Afro-pessimist thought.

Described as "stark, raw, [and] a bit terrifying," Buchanan's environmental sculptures of the early 1980s are an encomium on permanence, materiality and racialized ambivalences (Waddell, 1985). Often taking the form of ruins, Buchanan's public sculptures in the Southeast are predicated upon a conception of a future that has already arrived, constituting a disavowal of a productive or generative futurism. Works like Unity Stones were mixed with black pigment so they would be intrinsically black. These hybrid concrete/clay forms sculpturally reiterated what Buchanan saw as a continual process of ruination. Literally or phantasmically suggesting black subjects unmade by the very processes of subjugation, Buchanan's work exists in the uncomfortable space between object and thing, and in their current states—decrepit, forgotten, overgrown and broken—continue to question the social promissory limits of sculpture. Sharing a similar fate, seriously compromised, dispersed and/or disappeared, many of Buchanan's smaller sculptures from this period are even worse off in that they are no longer extant.

Ruins themselves are indicative of this break between objects and things, as structures that are no longer useful in the ways imagined by their authors/architects. Because of this, ruins have a long and considered position as philosophical touchstones, connoting elastic time. They are: "time out of joint," (Connor, 2006, p. 164); "a remnant of, and portal into, the past," a "fragment with a future [...] remind[ing] us too of a lost wholeness or perfection" (Dillon, 2011, p. 11); an "obscure antagonism [...] taking place between nature and matter," (Simmel, 1958, p. 384); sites of "wholesome hankerings [...] of our fearful and fragmented age," (Macaulay, 1953, p. 455); and "neither a spectacle nor a love object. It is experience itself. [...] memory open like an eye, or like a hole in a bone socket that lets you see without showing you anything at all, anything of the all," (Derrida, 1990/1993, p. 68). Broadly, ruins signify a temporal in-between-ness, at once confirmation of a past long gone and the suggestion of an entropic future far away. In this reading ruins are a compression of time, an enfolding of a tensile continuum; but ruins, as they are apprehended, actually belong to that neglected and fugitive tense: the present. 'Ruination,' the present continual verb form asserting ruin as a condition, may be the most apt way of understanding what Buchanan's Georgia installations enact.

Focusing energy on ruination, Buchanan's sculptural ruins consistently resist nostalgic reverie and romantic retrenchments into the past. Of course, there are romanticized readings of ruins, but ruins are opportunities for memory and countermemory only insofar as they are aesthetically arranged: "The stumps of the pillars of the Forum Romanum are simply ugly and nothing else, while a pillar crumbled—say, halfway down—can generate a maximum of charm" (Simmel, 1958). Buchanan's Georgia ruins importantly lack this charm. They seem allergic to the kinds of affective attachments charm relies upon; neither pitiable nor picturesque, they are ugly (and not simply so), insistent, craggy.

There is a certain strain of postmodern artistic practice that calls for ruination, and many artists that claim ruination as an artistic strategy. This rarely works out. The Scandinavian artist pair of Elmgreen & Dragset, for example, claimed they wanted their installation of a pop-up Prada store in Marfa, Texas—actually located on the border of economically depressed Valentine, Texas—to fall into ruin: "As we purposefully will not preserve Prada Marfa, it will eventually become a ruin so that even in a future decayed state it will remain relevant to the time in which it was made" (Mark, 2005). This site-specific sculpture of a small Prada store with a perpetually locked door, an unintentional symbol of the enormous wealth gap between the ultra-hip Marfa and its economically depressed neighbors, has been subject to vandalism/protest at least three times since its unveiling in 2005. Each time the installation has been dutifully patched up and restored to its original condition. What Prada Marfa demonstrates in-contra is that ruination doesn't occur because we want it so; ruination occurs because of a consistent and collective forgetting. Ruination demands an absence of care—neither an iconoclastic drive to destroy, nor a caregiver's promise to keep. Ruination is an effect of thoughtlessness and inattention.

In this way the negative politics of Buchanan's public works considered here are evidenced by their material condition, their continuing unimportance and relative obscurity, their intentional neglect and decay, their resistance to cataloguing and condition reports, in short, their utter and complete ruination. It makes writing about them a tricky ethical proposition, as giving attention might chip away their political charge.

Throughout this essay I also want to consider her work as an answer to a contemporary attentiveness to Afrofuturism(s). To be clear, this comparison is anachronistic, as Afrofuturist discourse is a product of the 1990s, nearly a decade after Buchanan left Macon, Georgia (Bristow, 2013). But then the same could be said of Afro-pessimist discourse invoked in this essay. Yet many of the core concerns of these discursive formations, related but different, can be teased out via an examination of Buchanan's public sculpture.

Afrofuturism was originally coined, somewhat tentatively, by Mark Dery in his 1994 article "Black to the Future." After a telling series of epigrams by George Orwell, Alain Locke, and Def Jef, Dery trains his critical eye on "Speculative fiction that treats African-American themes and addressed African-American concerns in the context of twentieth-century techno-culture—and, more generally, African-American signification that appropriates images of technology and a prosthetically enhanced future—might, for want of a better term, be called Afro-Futurism" (p. 180). The rest of "Black to the Future" is comprised of interviews with three practitioners of this nascent genre informed by cyber/techno-culture. Like many discursive neologisms Afrofuturism has mutated and clarified its multiple positions over time. One of Dery's interviewees, the sci-fi writer Samuel R. Delany, many years later offered a simple formula for Afrofuturism during an interview with Paul Miller (aka DJ Spooky) published in the recent "The Shadows Took Shape" exhibition catalog: "If you happen to be black..." and "If you write stories that deal with some aspect of the future of culture or technology or anything else—well, you're writing Afrofuturism" (p. 54).

Afrofuturism, since its introduction as a critical term, has pieced together an array of overlapping and disparate practices/concerns shared between artists, musicians, writers, and other cultural workers. Along the way, the discourse has developed to carry an institutional currency, and thus an attendant historical narrative dotted with heroes: Sun Ra, Octavia Butler, RAMM:ΣLL:ZΣΣ, DJ Spooky, Samuel R. Delany, and the Wu Tang Clan. These are complex figures with wide-ranging bodies of work, yet Afrofuturism is most commonly and narrowly positioned as an escapist critique (Bristow, 2013), belying its constitution with what counts as 'sci-fi' content, rather than suggesting an approach to process and/or praxis. The work and writings of Cauleen Smith, who focuses on Sun Ra's music and archives, posit that Afrofuturism involves a particularized praxis having to do with certain formal and structural considerations. In a similar way I introduce Buchanan's work in relation to Afrofuturism not to gain her entrance into this ever-emerging corpus—much of Buchanan's work directly resists the major lineaments of Afrofuturist practice and literature. Rather, I wish to posit Buchanan's artwork as a revealing foil to some of the overly utopian tendencies within the genre. Buchanan's sculptural ruins might be closer in spirit to the definition of Afrofuturism proffered by Kodwo Eshun, that "[Afrofuturism] eludes humanity, which it understands as a trap. It envisions the present from the perspective of a future in which the prospect of perspective is itself extinguished" (2013, p. 118). Eshun is drawing attention to a politics of Afro-pessimism, without naming them as such, that might infuse an Afrofuturist project. Its "envisioning of a present" is tied to the anti-humanist extinction of perspective—in all the multivalence of that word. This is the difference between making allegories of the past (slave ship as space ship), and "renarrat[ing] the past" (Ramírez, 2008, p. 186).

Buchanan's Georgia ruins renarrate the sites on which they're placed, each one aligned with a particular thorny Southern figure and a complementary figuration of blackness. In their presentness they suggest an "extinguishing" politics of negativity that can only enrich and round out our current fascination with Afrofuturisms. Her public sculptures in Macon, Georgia and its surrounds also tease out a new tendril in Afro-pessimist thought, where Jared Sexton posits, "Black life is not lived in the world that the world lives in, but it is lived underground, in outer space" (2011, p.28). Buchanan's work adds the ability for black life to exist on the ground and in things, a kind of mooring to non-human elements that reveals the political stakes of describing blackness.

Because of my own disciplinary biases I should note that from an art historical perspective Buchanan's work from her time in Macon could easily be grafted onto extant histories of Land Art; like her contemporaries Buchanan was interested in the ruptures in the symbolic bond between landscape and permanence. But whereas Land Art invested heavily in the desolate, unpopulated expanses of the American Southwest (and either ignored or fetishized the land's relationship to indigenous people), Buchanan's work remained local to Macon, Georgia, and thus carried with it a series of meanings specific to Georgia's history of slavery and its legacies. Buchanan's radically negative and pessimistic thesis was that in this landscape ruination was already at the door—indeed it had been for some time.

In suggesting that we couple a politics of Afro-pessimism with Buchanan's Georgia installations, I attempt to resist one of the pitfalls of what critic Mieke Bal calls biographism, which would elide Buchanan's work with the artist herself, who is by all accounts benevolent, charming, open, engaging and friendly (Bal, 2002). Indeed, during my visit to Macon, many of Buchanan's friends and colleagues were only too happy to wax on about Buchanan's affable personality. But an Afro-pessimistic politics and an outgoing, engaging personality are not mutually exclusive. Indeed, this paradoxical relationship holds true for Buchanan's closest associates; the warm feelings folks in Macon still have for Buchanan seem to rest alongside their perplexity and disinterest (and sometimes even dismissal) of Buchanan's large-scale public sculptural work. When asking Buchanan's Macon community about trips they might have taken to Brunswick to see Marsh Ruins, or about the dedication of Ruins and Rituals or Unity Stones, nothing was said about the sculptures themselves, only that they remembered that it was hot and/or inconvenient. In other words, there were ontological crises to be had, but they were tied to the nagging existential questions muggy Georgia days elicit.

Buchanan's years and work in Macon thus constitute a black hole, of sorts (as per this special issue of Rhizomes). Buchanan's public works in Georgia are notable within her oeuvre for their large and ambitious scale. They invert the heroicism aligned with Modernist sculptural programs by hinging on an ability to dodge detection. In yet another paradox of this particular time in Buchanan's artistic life, these were also the years of highest visibility and institutional sanction for Buchanan's work, as Buchanan received both a Guggenheim Fellowship and a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship in the early 1980s, in addition to a number of regional and state public funding grants. She also served as a United States delegate to a women's art conference in Copenhagen in 1980 (Son, 2012). Months of careful planning and an array of co-conspirators and collaborators were required to successfully complete these public installations. They are projects of the longue durée, and may be the artist's most personal works, as they required of her a tremendous amount of time and effort. That Buchanan's public projects remain invisible and unremarkable to those whose daily lives bring them in contact with them, intimates the installations' queer position within Buchanan's larger oeuvre, and might gesture towards Buchanan's own queerness.

During her time in Macon, Buchanan built and maintained close relationships with a small coterie of white gay men, some of whom were framers, gallery owners, and interior decorators. Buchanan made several works for her friends (most have never been exhibited) memorializing her queer affective bonds with them; a small glittering tower of sequins, trinkets, and campy collage (figure 4), for example, or a booklet of drawings of ham sandwiches (an extended in-joke reference to a close friend's trick-gone-wrong). She was familiar, then, with the worldviews of white gay men living in Macon and, as her work attests, shared a sense of humor and style.

Buchanan's own queerness is a stickier thing: she had long-term relationships with women but never identified as a lesbian. Thus it would be a mistake to attribute that particular identity to her. As Leila J. Rupp remarks in"Loving Women in the Modern World," "there are many and various ways in which women love other women," and not all of them align neatly with an identity category we name "lesbian" (2009). To Buchanan's friends, her relationships with women were another fact about her, maybe just as paradoxically apparent and curious as her blackness—both of which her Macon friends mentioned but never spent a great deal of time elaborating on for me. I am also mindful of the fact that Buchanan's sexuality is never discussed in the literature about her, and that this is inversely proportionate to the times that her blackness is referenced/invoked by writers (myself included). For me, I mention Buchanan's queerness not because it appears explicitly within the work, but because it is so conspicuously absent, operating as another lacuna within Buchanan's complicated oeuvre.

In focusing my energies here on Buchanan's Afro-pessimism and black negativity, I don't wish to suggest that all, or even most of Buchanan's work is governed by such principles. I want to reveal a strain of interest, a way of working particular to Buchanan. Buchanan's varied, important, and woefully under-reviewed artistic practice demands greater scrutiny, and a good-faith attempt to move beyond the cloying language attached to her work that sometimes even Buchanan herself put forward. As such, this is my way of opening out the field a little more, so that more of the dark can come in.

II

I won a contest in school because we had coloring every day. We had to color people and other things in our book. Well, the only unbroken crayon in my box one day was brown, so I colored the people brown. Nobody used that color for people. I got a gold star by my name in art, and that's how it all began... (Waddell, 1985)

This anecdote, far from being a trivial story about a coloring contest, reveals a host of antimonies, which play out over the course of Buchanan's career as an artist. The decision to use the brown crayon was borne out of necessity, not an Afro-centric consciousness; and yet, this is precisely the ground on which a young Buchanan, attending a segregated school where the dominant worldview precluded the notion of brown people in pictorial representation, was rewarded. Much of Buchanan's pre-Macon life is often represented both by the artist and her few chroniclers through the lens of blackness and rural poverty. Oftentimes this is done to provide an originary point of contact for Buchanan's post-Macon work. To adequately describe Buchanan's work that she created while living in Macon, some of these biographical details must be attended to and complicated to counteract their deployment in an otherwise treacly portrait of the artist and her work.

Most biographical sketches of Buchanan make mention of her father, Walter Buchanan, who was the dean of the School of Agriculture at South Carolina State College. As a little girl, Buchanan would accompany her father on trips to visit and sometimes stay the night on sharecropper and tenant farmer lands. South Carolina State College was in those days known as the Colored Normal Industrial Agricultural and Mechanical College of South Carolina, a literal index of the 1896 South Carolina statehouse mandate to establish "a normal, industrial, agricultural, and mechanical college for the higher education of the colored youth of the state" under the management of a separate board of trustees and a "separate corps of professors... [with] representation given to men and women of the negro race." (Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1902). In other words, the school was an immediate implementation of the separate but equal doctrine, as the school was established the very same year as Plessy v. Ferguson. South Carolina State College catered to students of a lower socio-economic class than better-known historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) such as Spelman or Morehouse.

Buchanan's relationship to her father's line of work is often foregrounded to justify and authenticate the content of her post-Macon work, wherein she developed an iconographic and sculptural language of shacks and other improvised shelters, but not to meaningfully comment on experiences of segregation that might have informed her work and practice. The bulk of writing on Beverly Buchanan is focused on her later works. These jury-rigged shack sculptures are often positioned within the reparative rhetoric of the noble and dignified poor. They are simply regarded as representations of the "indomitable spirit" (The Chrysler Museum, 1992) of their "poor but proud" (Morris & Woods, 1988) inhabitants. This reading of Buchanan's work is no doubt informed by Buchanan's own statements about her work as a "celebration of the spirit of people I had known who lived in dwellings called 'shacks'" (Andrews, 1988). The Protestant ethic that surrounds such work, "love for one's neighbors and respect for hard work and the land" (The Chrysler Museum, 1992), ameliorates many of the affective experiences of poverty that aren't neatly redeemable and, furthermore, conveniently ignores the daily ambivalencies endemic to poverty. "Life, humor, and dignity" win the day (Ibid.)—whereas anxiety, depression, trauma and all that daily survivorship entails is lost. Yet as Buchanan herself noted, surreptitiously revealing her anxieties around depicting the domiciles of the rural, often black, poor, "I expected blacks not to like [the shack sculptures], but they weep" (Slesin, 1990).

Also highlighted in existing biographies is Buchanan's dual interest in science and art: during the late 1960s and early 1970s she worked as a public health worker/educator in New York City and East Orange, New Jersey. Buchanan's job involved "talking about lead poisoning, designing posters, and meeting with community groups in snow storms" (Waddell, 1985). At the same time, Buchanan was also forming mentor relationships with Romare Bearden and Norman Lewis, both former members of the Spiral group. Buchanan took art classes with Lewis at the Art Students' League. It was while enrolled there that Buchanan began making large abstracted drawings of walls, mostly black in coloration (figure 5). She also began to experiment with small concrete sculptural forms, cast from piecemeal molds made of wood and brick (figure 6). These "City Ruins," as she would call them, were dubbed "frustulum/frustula" (literally "piece" or "fragment" in Latin) by Buchanan's gallerist, Jock Truman. The frutstula are a product of a conceptual language developed by Buchanan directly out of the landscape she encountered daily in New Jersey and New York City:

My interest in walls involves the concept of urban walls when they are in various stages of decay; walls as part of a landscape. Often, when buildings are in a state of demolition—one or two structural pieces (Frustula) stand out that otherwise, never would have been "created." This state of demolition presents a new type of "artificial" structural system piece that by itself (its undemolished state) would not exist. These "discards" or piles of rubble can be pulled together to form new systems. These new systems are very personal statements to me. They are inspired by urban ruins but are created, "in my own image" by me, in concrete and painted with dark paint. Deceptively, they appear to be black. (One of my dreams: to place fragments in tall grass where a house once stood but where, now, only the chimney bricks remain.) (Buchanan, n.d.).

Given her background as a health educator, the term Frustula must have also been a playful riff off of "fistula," an abnormal passage between two organs or between an organ and the skin. Buchanan's insistence that her sculptural system was "created in her own image," draws attention to the ways in which ruins, positioned as external elements of the landscape, are the bearers of cultural meanings inimically tied to embodied notions of selfhood. Buchanan continued to make these frustula well into her time in Macon, where she further diversified her artistic practice in response to her new surroundings. Within a year of moving to Macon, Buchanan had a solo exhibition of large paintings and had developed a strong network of patrons, friends, and interlocutors.

To be clear, there are other events that inform Beverly Buchanan's personal and artistic constitution, but are forgotten either because they prove inconvenient or embarrassing for the artist and/or writer. For example, as an undergraduate student in North Carolina, Buchanan was involved in the Civil Rights movement. As Buchanan later recalled on Marcia Yerman's New York public access show Women in Art:

[On] one of the picket lines in front of Woolworth's [...] a group amassed and attacked us, and I jumped one man and tried to choke him. And that was an extremely embarrassing situation, I was asked to leave the line and not return, because we were non-violent. I was never proud of that.

Important here is not necessarily Buchanan's shame or embarrassment, which is present as the artist seems to visibly surprise herself in mentioning the incident, but that Buchanan was involved with the Civil Rights movement at all. This basic fact about Buchanan hardly appears in the extant literature. Exiled from the line for crossing another "line," Buchanan's participation—her anger and her sense of self-preservation—have also been exiled from her biographies. I only mention this (as I mention Buchanan's queer sexuality) to hint at what must be a fuller, richer life, rife with the contradictions and emendations that any life worth living is bound to have.

III

Shortly after Buchanan moved to Macon in 1978 she sent out a picture-postcard of herself next to a handmade sign reading "Hunger and Hardship Creek." This cheeky missive served as a marker of her new life in Macon, Georgia. Typical of Buchanan's impish humor, the postcard also played on persistent stereotypes regarding the South. And she's not the only one: an author or editor in Contemporary Art/Southeast captions an image of one of Buchanan's frustula with a sentence displaying acerbic sarcasm or gleeful pride (both?): "The artist, by choice, works in Macon, Georgia" (Perkins, 1978/80).

Although Buchanan had a financial cushion when she arrived in Macon, she soon ran out of money and was quickly bartering work for utilities and rent. Within that year Buchanan had made inroads with board members at the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Macon (MAS). In a letter to Buchanan's New York gallerist, Jock Truman, the Director of the MAS, Douglas Noble, makes clear that the construction and placement of a new large-scale sculpture, Ruins and Rituals, originated with Buchanan pitching the installation to MAS. The sculpture's proposal "involved the use of several massive concrete footers which will be arranged, shaped and stained to produce Ms. Buchanan's landscape piece." As the letter goes on to note: "The site selection for the piece was particularly important; and we are pleased that an open, moderately-wooded area, which is part of our Harry Sitwell Edwards Arboretum, fits Beverly's needs for this particular project" (Noble, 1979).

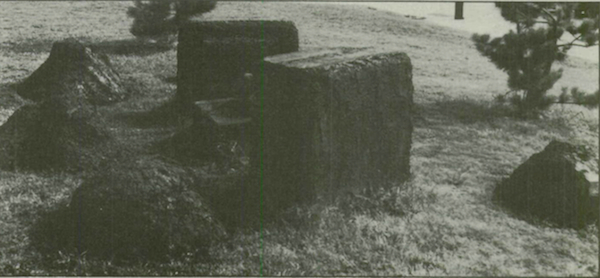

Pitched by Noble as "a landscape piece," Ruins and Rituals is comprised of four large square footers, and seven smaller cast concrete pieces. The footers were initially stained a variety of subtle colors, mottled lavender and ochre (no longer visible), to play off of the light of the site. Buchanan, writing about Ruins and Rituals, described many "stand-spots" from which to view the "different shadows and colors" of the work (Buchanan, 1979). The footers were taken from an abandoned restaurant or a used car lot (accounts vary), and Buchanan shaped them to appear like cubic sarcophagi. Each of the large footers exhibits a deep, but not complete, cut into its interior about six inches from their top (figure 7). The small cast cement pieces, many looking like bricks or dangerous stepping stools, are opportunities to step up and survey the installation's scene from an ever-so-slightly elevated place.

Perhaps the reason for the sculpture's placement in the arboretum was merely because Buchanan found the landscape and the light to her liking—both Douglas Noble's letter to Truman and Buchanan's artist statement rest on this notion. But even if it was unwitting (and I'm not ready to concede that yet), Buchanan's sculpture plays off a particular politics of its site. As Noble noted in his letter, the arboretum where Ruins and Rituals is placed is named after the Macon-born novelist and poet Harry Sitwell Edwards, whose most famous work was the epistolary Eneas Africus (1919): a pro-slavery Uncle Tom ode first serialized in the Macon Evening News. Once it was bound in novel form, Eneas Africus went on to sell at least three million copies. The story concerns a slave, one of a described "vanishing type" named Eneas Tommey, who is charged by his master, Confederate Major George E. Tommey, to take a bounty of heirlooms from his master's plantation to the family home in Jefferson. But there are many counties named Jefferson and it takes a befuddled yet well-intentioned Eneas eight years to find the right one. Capers ensue, and by the time Eneas dutifully completes his task slavery has been abolished; but no matter, Eneas being of that "vanishing type" is only happy to self-enslave once he is reunited again with his master (Edwards, 1921).

The Harry Sitwell Edwards Arboretum at the Museum of Arts and Sciences in Macon is thus a charged site. Naming public places after figures who (re)iterate an anti-black politics is not peculiar to Macon, Georgia—this was an especially common form of public address in times where new possibilities for economic/social mobility for black and brown people threatened a status quo in the Jim Crow South. The arboretum has since been renamed The Georgia Power Sweet Gum Trail and the Elam Alexander Outdoor Classroom, after the educational philanthropist and architect Elam Alexander, who died when Edwards was a mere eight years old.

But Buchanan was responding to more than the namesake of the Arboretum. Indeed her response was much more material; in 1964 the museum moved Kingfisher Cabin, Sitwell's writing retreat, from the outskirts of Macon onto the museum's grounds in the arboretum. Although built after Eneas Africanus was written, Kingfisher Cabin nevertheless stands in for Sitwell's presence and his achievements as a writer. Placed within spitting distance of Kingfisher Cabin, Ruins and Rituals articulates a conversational opposition to Sitwell's studio—the production site of so much pro-slavery propaganda. When Buchanan writes of the "different shadows and colors" of her installation, she might also be talking obliquely about the installation's proximity to Kingfisher Cabin. One of Ruins and Ritual's footers is located a small distance away from the other three (figure 8). When approaching the site from low-ground, the four footers seem to congregate and share space, but from the side it's difficult not to anthropomorphize the separate footer. Away from the group, this footer is closer to Kingfisher Cabin. The footer, a rough-hewn sarcophagus, gestures towards a source of anti-black sentiment and its inevitable consequences.

Many prefer to see Buchanan's choice of site as benign, her choice of material as novel. When Ruins and Rituals is mentioned by critics, it is either surmised to share a tie with prehistoric lithic sites (Lippard, 1983) or African spiritual systems. Lowery Stokes Sims describes Buchanan as "like the shaman/artist in New World and African cultures" making "runes/ruins" and "conjur[ing] the magical quality of the art-making process which first captivated humans thousands of years ago" (Sims, 1981). As critics like Lippard rightly note, the concrete footers and small cast pieces are only one third of the installation. Two other parts exist, but are undocumented. One part was placed further out in the woods, and the third part sunk without witness by the artist in the nearby Ocmulgee River. Like Sol Lewitt's Buried Cube Containing an Object of Importance But of Little Value (1968), Buchanan's secret components engender curiosity for any who know about them—but unlike LeWitt's conceptual gesture, Buchanan's may have more to do with the legacies and politics of blackness in the South. Buchanan points to, via her practice, the long history of racial supremacy and its attendant practice of disappearing black and brown bodies in the South. Buchanan embeds the unrecoverable, the unknowable, and the simply forgotten into her sculptural practice.

IV

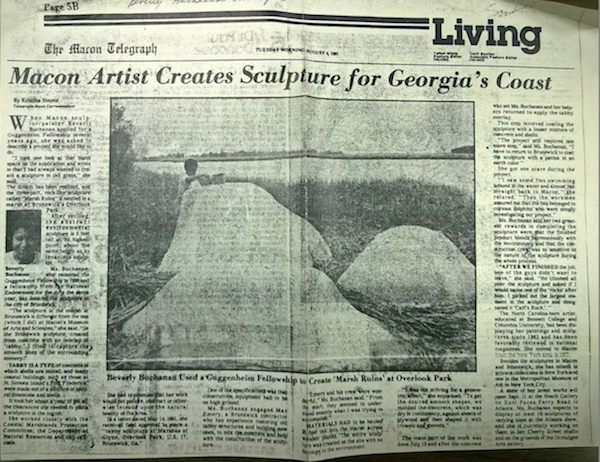

You could be forgiven for overlooking Marsh Ruins. The sculpture exists at the edge of the Marshes of Glynn State Park, a modest parcel of parkland overlooking an expanse of saltwater marsh. Comprised of three sculptural bodies, two swelling round forms and another that looks like a hill quartered, Marsh Ruins nearly disappears in its surrounds, despite the sculpture being nearly five feet in height. Although not fragments/frustule precisely, this is the closest Buchanan came to realizing her dream of "fragments in tall grass." Daily the sculpture is flooded by the tide (figure 9) which, years after its installation, has left the sculpture in a truly pitiable state: cracked, broken, and partially buried in smelly marsh mud (figure 10). Tiny crabs and spiders scurry out of the ground, creeping into the cracks and finding shelter in the wrecked forms—it is to them no doubt a tired and familiar part of their landscape, no different than an overgrown tree stump. Just another place to hide.

Unlike Ruins and Rituals, the politics of Marsh Ruins' black negativity is located in its materiality. The three mounds are made of tabby, a concrete of Spanish Colonial origins made with oyster shells and lime. Tabby is a charged material, especially for a sculpture sited along the Georgia coastline, as many sugar and cotton plantation buildings were made with the stuff, particularly slave quarters and sugar houses (Coulter, 1937). Ruins of these tabby structures can still be found on the Georgia and Florida coast: St. Simeon Island, Sapelo Island, and Ossabaw Island, among others (figure 11). The oyster shells create a surface that goes beyond rustic—it is sharp, unfriendly.

Tabby would be an unlikely building material had the Southeast's antebellum economy not been predicated on slave labor; its constituent ingredients are easily found along the coast (chiefly from Native American middens of oyster shells), yet the process of making the lime from shells is labor-intensive, and some scholars estimate that this process took up to thirty percent of the time needed to erect a tabby structure. The (slave) labor, of course, was not at all costly for plantation owners (Sheehan & Sickles-Taves, 2002). Perhaps unsurprisingly, after the Civil War the use of tabby as a building material grinds to a stunning halt, speaking to the difficulty of its production/procurement and the ease with which slave labor masked such difficulties.

Interestingly, there was a small and localized boom of tabby building as a nostalgic reminder of pre-emancipation days: "Consideration should also be given to the fact that in a world turned upside down [from the outcome of the Civil War], traditions simply may have meant more, and tabby helped fill that void" (Sheehan and Sickels-Taves, 2002, p. 22). Darien, Georgia was the epicenter of this revival, and the Marshes of Glynn are only thirty minutes away.

Yet for all tabby's widespread and generic use in the Southeast, the Marshes of Glynn is also a particularized mythological site for Georgians. Most Georgians growing up in the 20th century would have memorized part or all of "The Marshes of Glynn," a Romantic poem by 19th century Macon-born musician, poet, and confederate soldier, Sidney Lanier, as a standard part of school curricula (Bagwell, 2008). Lanier, writing after the conclusion of the Civil War, composed "The Marshes of Glynn," in part, as an idyllic balm to soothe anxious white Southerners that there were still many places in the South untouched by Northern industrialism. In his poem, death is always nearby, yet foiled by the bounty and beauty of the marsh. In Lanier's handling, the marsh is a "limpid labyrinth of dreams" full-up with the "ancientest perfectest hues/ Ever shaming the maidens" (Lanier, 1879). Unrelated to Lanier, yet a dozen years after Lanier composed his ode, Glynn County would be the site of the mob lynching of Wesley Lewis and Henry Jackson, two 21 year-old black men accused, but of course never convicted, of assault. The idyllic marsh itself is thus bound up in the disciplining and punishment of black bodies.

Buchanan used the bulk of the Guggenheim grant awarded to her in 1980 to complete Marsh Ruins, and her investigation into the coastal lands of Southeast Georgia was part and parcel of a larger practice of exploring and memorializing Georgia's forgotten black historical/archeological sites. Buchanan's studio assistant, Virginia Pickard, then in high school, recalls loading up Buchanan's car with small cast concrete sculptures/Frustula and driving out into rural Georgia. Together they would often stop beside small, sometimes abandoned, black churches, setting out looking for slave graveyards. The evidence of such burial places, some belonging to Gullah or Geechee communities, was usually obscured by the same overgrown foliage that now plagues Buchanan's own work (Honerkamp & Crook, 2012). Once Pickard or Buchanan found evidence of a slave graveyard (a few pieces of wood or stones placed in a particular alignment), Buchanan would retrieve a small cast concrete sculpture from her car, inscribe it with her initials, and leave it at the site. Similar to the hidden components of Ruins and Rituals, this action took on ritualistic significance as a way of honoring the forgotten dead. Sometimes Pickard or Buchanan would photograph the work, but these photographs (few are extant) were the only documentation Buchanan made of these works. Outside of Buchanan's barter-economy art yet conceptually related to her large-scale public projects, these mini-monuments are some of the clearest examples of Buchanan's evolving engagement with black death in the South (V. Templeton, personal communication, September 11, 2014).

Unlike the small slave graveyard sculptures, Buchanan's Marsh Ruins are more significant in scale, requiring the assistance of contractors and parks professionals, environmental clearances and a hefty pool of cash. Still, in the existing literature on Marsh Ruins, the connection between Georgia's raced architectural materiality and Buchanan's site-specific installation is achingly absent. Buchanan's sculptural intervention, unbeautiful and thick, plays contrarian to the Romantic language Georgians are inculcated to associate with that particular parcel of land. Made of a tough and hearty building material, one that unmistakably bears the historical trace of its close alignment with the Southern slave-labor economy, Buchanan took extra steps to ensure the triangulated connections between historical trauma, building practices and landscape (figures 12 and 13). Images of Buchanan installing the work show the artist staining the forms a watery brown color, marking these misshapen forms as topologically raced. Buchanan claimed this patina ensures the sculptures would blend with their surrounds (Simms, 1981). But in staining the tabby Buchanan knew that the stain would only "take" to the non-shell components of the slurry. The resultant flecked surface would have imbricated both brown and white in a lumpen political body.

When I set off to find Marsh Ruins, I was told that it was gone, now totally submerged; Google Streetview told me otherwise (figure 14). True: much has changed about Marsh Ruins, making it perhaps the most dramatic example of Buchanan's interest in ruination. The subtlety and beauty of Marsh Ruins' color is long gone, having faded with the sun many years ago. What remains reveals a different subtlety in the sculpture's structure; namely, Marsh Ruins was built in layers, tabby only being an inch or two surface poured atop a more traditional concrete substructure. A body missing parts of its skin, an onion partway peeled. A ruin in ruins (figures 15 and 16).

In an awful way (or perhaps happily), Buchanan's Marsh Ruins re-performs precisely the trauma of consignation it sought to point to. Its negativity lies in the unavoidable presentness of its condition, and the force of its structural statement is inimically tied to its peculiar ability to get (and stay) lost in plain sight. Buchanan's work absorbs the continual and numbing trauma of daily forgetting. Its condition, now radically different from when it was first installed (figure 17), would not be so shocking today if we had been paying attention all along. Its political force comes from how freely our dismissal was granted, and the tenacity with which it remains in place. When it disappears—and it will—I wonder if anyone will miss it?

And if by missing it, miss the point.

An addendum: Buchanan, who until recently was living with dementia in Ann Arbor, kept a photograph of Marsh Ruins above her bed, marking the installation as especially significant (figure 18).

V

"Cast down your bucket where you are" was the near-constant exclamation of Booker T. Washington's so-called 1895 Atlanta "Compromise" speech. Ignoring Washington's folksy refrain, W.E.B. DuBois eviscerated Washington's gradualism point-by-point just shy of ten years later in his essay "Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others." While it is not this article's project to recuperate Washington's speech, the antagonism directed towards Washington's wrong-headed steady-does-it programatic for black people was in the forefront of Beverly Buchanan's mind when she created Unity Stones and subsequently sited it on the lawn of the Booker T. Washington Community Center in Macon, Georgia. Perhaps the most visible and ham-fisted visualization of blackness in the trifecta of public projects examined here, Unity Stones (via its titling) would seem to indicate a move away from negativity and towards a reparative politics.

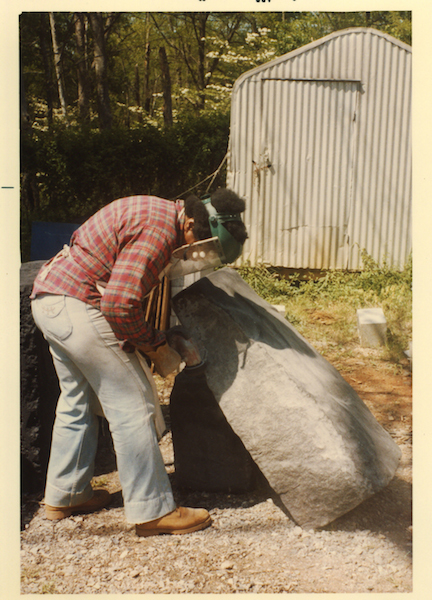

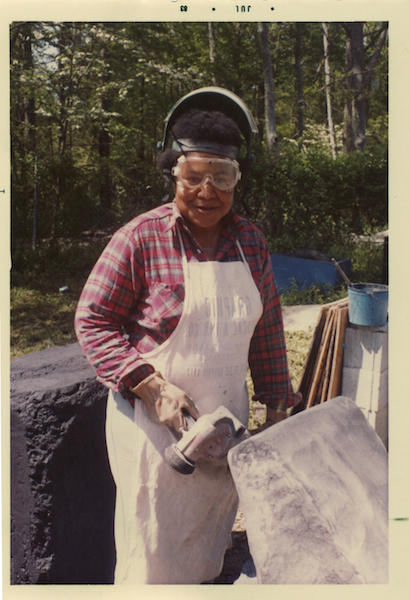

But Buchanan's understanding of the blackness within the work is more subtle; an article from the Macon Telegraph and News explains Buchanan's reasoning thusly: "Buchanan chose black Georgia granite for one of her nine stones because she wanted different textures in her work. The different textures also represented the different sides of Booker T. Washington, she said" (Long, 1983). The article does not go into more detail about what Buchanan means by the "different sides" of Booker T. Washington, but one only needs a basic understanding of black history to know that Washington is often seen as not radical enough in his approach, playing too eagerly into the assumptions of white power brokers. Formally the sculpture iterates this idea: it is essentially a heraldic arrangement of elements, bisected by the "black Georgia granite" (figure 3). With the six small mounds that surround the two larger rectangular cast concrete forms, a meeting or gathering place is suggested (figure 19). Yet, if this is so, the two rectilinear forms would practically block any kind of group communication or communion. Buchanan's arrangement of Unity Stones is more face-off than sharing circle. The line in the sand (well, grass) is bisected quite literally, in hard granite. Sanded and stripped, the granite still indexes the stress and fatigue of Buchanan's process (figure 20), documented in a series of photographs taken while the artist worked on the installation from her temporary studio outside of the Museum of Arts and Sciences (figures 21-23).

One of the striking features of these photographs is the saturated blackness of the cast forms behind Buchanan. Unlike Ruins and Rituals or Marsh Ruins, the concrete bodies of Unity Stones are dyed-through with black. Lowery Stokes Sims, then Associate Curator of Twentieth Century Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art (which had just acquired one of Buchanan's works, Wall Column (1980), when this statement was written) provides the best description of Buchanan's working method:

...old bricks must be used as molds. The pigment is produced from rocks which must be searched out in the landscape, and then carefully cracked and ground down to powder. This pigment is added to the form at a precise moment so that it will weather when the piece is placed out-of-doors, and the precise formula of concrete, clay and pigment has been combined carefully to enable them to maintain their cohesion (1981).

Similar to the work required to make tabby, Buchanan's material process utilizes cheap and ubiquitous materials in a labor-intensive process. Forging a link between historical black labor in the South and the contemporary artist's labor, Buchanan also often added Georgia clay to her admixture, solidifying the form's connection to its place of origin. The artist remarked on the politics of color in Unity Stones, "The black concrete is uniform. It's the same mixture all the way through." Buchanan told art historian Patricia Phagan in a 1984 Art Papers interview, "... some people have gone by in the early evening and been a little frightened by [Unity Stones] and prefer to see it 'full-sun'" (Phagan, 1984, p.17). Mirroring her comments at the African-American art forum that began this essay, Buchanan continued to refer to the installation as the site of potential violence despite its rhetorical claim of unity.

Unity Stones' placement in front of the Booker T. Washington Community Center marks Buchanan's psycho-geographic and racialized location; she identifies the center as being "in her neighborhood," but states that her placement was chosen so that "many people, who might not have a chance to view it at the museum [of Arts and Sciences], could see it there" (Long, 1983) (figure 24). Like the "different sides" of Booker T. Washington—or rather, varying readings on Washington's politics within his milieu—Unity Stones is also partly a marker of Buchanan's politics of black negativity. Its negativity resides, as in Ruins and Rituals and Marsh Ruins, in its materiality and site placement along a continuing geography of blackness and visibility.

Unity Stones still sits there, not three blocks from Buchanan's former residence on nearby College Street. While College Street is full-up with generous stately homes, in the late 1970s and early 1980s the area was less developed, less polished. It was, and still is, a boundary between a middle/upper class white population and a working class black population. This was one of many lines that Buchanan treaded in both her work and her life.

The Booker T. Washington Community Center now houses the Stone Academy (the director claims no affiliation in name), a STEM afterschool program with mostly black enrollment. When I asked the students and administration about the work, no one really knew much about it. In fact, some questioned its very existence.

VI

My excavations here, while bound up in the particularized politics of materiality and site, are somewhat speculative. No one has offered this kind of reading of Buchanan's work; yet Buchanan's careful intentionality with her public projects in Macon cannot be denied. Perhaps she always intended for her public sculptures to be mostly invisible, or to be inculcated in more palatable conversations surrounding land art, sculptural form, and the play of dappled light through the trees—but as an artist aware of and invested in the punishing vicissitudes of black history, it's hard to believe this invisibility comes without political implication (figure 25). As Fred Moten writes in "The Case of Blackness," "The lived experience of blackness is, among other things, a constant demand for an ontology of disorder, an ontology of dehiscence, a para-ontology whose comportment will have been (toward) the ontic or existential field of things and events" (187). In making works that encircle, augment, abut, and contain within themselves the genius loci of racialized/anti-black violence, Buchanan was engaged in "a transvaluation of pathology itself, something like an embrace of pathology without pathos" (Sexton).

![Figure 25: Beverly Buchanan, Unity Stones [detail], concrete and black granite, 1983.](fig25.jpg)

The power of thinking through Beverly Buchanan's Georgia installations at this moment in time is that they may also act as complicating, and thus enriching, milestones to the current attention paid to Afrofuturist modalities. Buchanan's works, if they are about futurity at all, are about the past's lack of a dependable one for black people. They suggest a tie between blackness and ruination, a presentness both with and without a future. It would not be too much to argue that the temporal politics Buchanan channeled in the early 1980s have extended well into the present, despite the sometimes loud and dangerously elisive mynah birdcalls of post-racialism today. Because of their insistence on ruination, the continuing presence of the lacunae and fissures that, paradoxically, are the absent/visible tailings of chattel slavery in the United States, Buchanan's work is positioned in situ, geographically, to best explore these anxious historical antimonies and legacies. Afrofuturism has been the name for the generic place (space?) where non-fictive (and often non-recuperable) histories of blacks in the diaspora intersect speculative fiction: and the question is whether Afro-pessimism is the word for a work that reveals, for all its present invisibility, a politics of negativity?

Perhaps form can also fill language's void.

* * *

Since finishing this essay that void has only yawned out.

Beverly Buchanan passed away not even one month ago, on July 4th, 2015. I never met her, even though I completed the bulk of this text while she was still alive in Ann Arbor, MI. I knew, even as I began my research, that it was unlikely I'd ever meet her; dementia foreclosed that possibility. Instead, I was in contact with her friend and caretaker, Jane Bridges, who assured me that Beverly understood and was excited about the recent attentions of a small group of researchers. I am extremely lucky and grateful to count myself amongst them.

Concurrent with my initial research for this article, my father began to assume a greater role in caretaking for his own father, who was (and still is) living with dementia. Dishwasher pods mistaken for hard candy... Restless nights of paranoid fantasy... Doors locked and guns confiscated... his pervasive belief that my father—his son—is actually his own father. All these events have proven that dementia is unruly—its slow violence stripping inherited notions of agency and personhood. The kindest people (those afflicted and caretakers alike) are more prone to lash out. Stress inflects every decision. My grandfather and Beverly Buchanan could not be more different; as opposed to Buchanan he was (is... was...) a white, conservative man, a former Goodyear executive, and a grumpy contrarian in his later years. He took care of his wife as she lived with and finally passed away from Alzheimer's, gently spoon-feeding her meals when she was too far gone to perform the task herself. I learned a particular degree of empathy and kindness from watching him do that. I learn this lesson again from my father.

At a time when so many in the US are focused on the egregious and spectacular deaths of black people at the hands of juridical authority, there are also quieter deaths of black people, transitions made in hospice beds in far away Northern states. Michigan. A name adapted from Algonquin. Another stunning example of ruination and misapprehension. Beverly Buchanan's work has much to say to the current discursive threads of Afro-pessimism and Afro-futurism, as I've tried to show here, but her legacy is no doubt a now, sadly, historical example of an artist asserting, in a particular place (and here I refer not just to the South but to the entire US) rife with histories of black death and enslavement, that black lives matter. Insisting on this as a conceptual crux of much of her artistic output doesn't delimit the kind of artist Buchanan was (is... was...); rather, it opens out the possibility that Buchanan's work will only grow in import. I just wish she were around to see that happen.

I don't know whether Buchanan was cremated or interred in the ground; and given the almost singular focus on public sculpture in this article, I am ashamed that this was one of my first questions upon hearing the news. Would there be a site, with a headstone? Would it be rough-hewn and instrinsically black—granite or dyed concrete? (But it's too much to ask that an artist design their headstone to fit within the conceptual parameters of their practice, right?) Could I visit, assess its care, and perform a kind of devotional cleaning? These questions are the ones I was actually asking about Buchanan's Georgia sculptures not one year ago. Circling back to the same questions, but under newer, grimmer conditions: this is not a welcome return.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, I found out the news of Buchanan's passing via Facebook, from one of Buchanan's friends from her years in Macon, Georgia. Because of Buchanan I now have my own relationship to that special and complex place. I recall incredible-but-true stories told to me over a half-way decent diner breakfast, drinks and laughter shared in well-appointed homes, night walks, a dead-end visit to the local television station, an afternoon spent gazing at the mounds of Ocmulgee National Monument park, and zealously driving four hours to see a sculpture that might not even be there.

— August 1, 2015 (Houston, Texas)

References

Andrews, B. (Ed.). (1988). Influences From the Untaught: Contemporary Drawings. New York: The Drawing Center.

Bagwell, T. E. (2008). When Poet Sidney Lanier Made the Marshes of Glynn Famous. Retrieved September 30, 2014, from «http://www.jekyllislandhistory.com/lanieroak.shtml»

Bal, M. (2002). "Autotopography: Louise Bourgeois As Builder." Biography, 25, 180-202.

Berlant, L. & Edelman, L. (2014). Sex, Or the Unbearable. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Bristow, T. (2013). "We Want The Funk: What is Afrofuturism to Africa?" In N. J. Keith & Z. Whitley (Eds.), Shadows Took Shape (pp. 81-87). New York: The Studio Museum.

Buchanan, B. (1979, July 30). Ruins and Rituals [statement]. Museum of Arts and Sciences, Macon, GA.

Buchanan, B. (n.d.). Statement: Wall Fragments—Series Cast in Cement. Truman Gallery, New York.

Code of Laws of South Carolina. (1902) In W. T. Harris (Commissioner of Education) Annual Reports of the Department of the Interior for Fiscal Year Ending in June, 1903. Retrieved September 30, 2014, from «https://goo.gl/PF3K2m»

Connor, S. (2006) "Ruins of the Twentieth Century" [panel]. Frieze, London. Transcribed in Frieze. (2009). Frieze Projects and Frieze Talks 2006-2008. London: Frieze.

Coulter, E. M. (1937). Georgia's Disputed Ruins. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

Derrida, J. (1993). Memoirs of the Blind: The Self-Portrait and Other Ruins. P. Brault & M. Naas (Trans.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1990).

Dery, M. (1994). "Black To The Future: Interviews with Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose." In M. Dery (Ed.), Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture (pp. 179- 222). Durham: Duke University Press.

Dillon, B. (2011). "Introduction: A Short History of Decay." In B. Dillon (Ed.), Ruins [Documents in Contemporary Art] (pp. 10-19). London: Whitechapel Gallery.

DuBois, W. E. B. (1903). "Of Mr. Booker T. Washington and Others." In The Souls of Black Folk. Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co. Retrieved September 30, 2014, from «http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/40»

Edelman, L. (2004). No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

Edwards, H. S. (1921). Eneas Africanus. Macon, GA: J. W. Burke Company. Retrieved September 30, 2014 from http://antislavery.eserver.org/proslavery/eneas-africanus/edwardseneas.pdf

Eshun, K. (2013). "Stealing One's Own Corpse: Afrofuturism as a Speculative Heresy." In N. J. Keith & Z. Whitley (Eds.), Shadows Took Shape (pp. 117-120). New York: The Studio Museum.

Hartman, S. (1997) Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hoelscher, S. (2003) "Making Place, Making Race: Performances of Whiteness in the Jim Crow South." Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 93, 657-686.

Honerkamp, N. & Crook, R. (2012). "Archeology in a Geechee Graveyard." Southeastern Archaeology, 31.1, 103-14.

Huyssen, A. (2009). "Authentic Ruins." In Hell, J. (Ed.). Ruins of Modernity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Lanier, S. (1879). "The Marshes of Glynn." Retrieved September 30, 2014, from «http://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poem/marshes-glynn»

Lippard, L. (1983). Overlay: Contemporary Art and the Art of Prehistory. New York: The New Press.

Long, S. (1983, October 24). "Environmental Sculpture Dedicated." Macon Telegraph and News, n.p.

Macaulay, R. (1953). Pleasure of Ruins. London: Thames & Hudson.

Mark. (2005). Prada Marfa, Wrap Your Head Around This One. Retrieved September 30, 2014, from «http://www.marfa.org/2005/09/prada-marfa-wrap-your-head-around-this.html»

Marx, K. & Engels, F. (1906). Manifesto of the Communist Party. Chicago, IL: Charles H. Kerr & Company.

Miller, P. & Delany, S. R. (2013). "Plexus Nexus: Samuel R. Delany's Pataphysics." In N. J. Keith & Z. Whitley (Eds.), Shadows Took Shape (pp. 47-56). New York: The Studio Museum.

Morris, K. & Woods, A. (Eds.). (1988). Southern Expressions: A Sense of Self. Atlanta, Ga: High Museum of Art.

Moten, F. (2008). "The Case of Blackness." Criticism, 50.2 (pp. 177-218).

Noble, D. R. (1979, May 15). [Letter to Jock Truman]. Museum of Arts and Sciences, Macon, GA.

Perkins, C. M. (1978/80). "Risks of Choice." Contemporary Art/Southeast, 2.3, 17, 41.

Phagan, P. (1984, January-February). "An Interview with Beverly Buchanan." Art Papers, 16-17.

Ramírez, C. S. (2008). "Afrofuturism/Chicanafuturism." Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies, 33, 185-194.

Reynolds, A. (2003). Robert Smithson: Learning From New Jersey and Elsewhere. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Rupp, L.J. (2009). "Loving Women in the Modern World." In V. Taylor, N. Whittier & L. J. Rupp (Eds.), Feminist Frontiers [8th ed.] (pp. 389-99). McGraw Hill Higher Education.

Schwartz, M. J. (2010). Birthing a Slave: Motherhood and Medicine in the Antebellum South. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sexton, Jared (2011). "The Social Life of Social Death." InTensions, 5.0, web. «http://www.yorku.ca/intent/issue5/articles/jaredsexton.php»

Sheehan, M. S. & Sickels-Taves, L. B. (2002). "Vernacular Building Materials and The Factors Conditioning Their Use: Tabby, A Case Study." Material Culture, 34.2, 16-28.

Simmel, G. (1958). "Two Essays: The Handle, and The Ruin." The Hudson Review, 11, 371-85.

Simms, K. (1981, August 4). "Macon Artist Creates Sculpture for Georgia's Coast." The Macon Telegraph, p. 5B.

Sims, L. S. (1981). Untitled essay for Heath Gallery, "Beverly Buchanan: Recent Sculpture" [exhibition]. Atlanta, GA.

Slesin, S. (1990, January 18). "The Shack as Art and Social Comment." The New York Times [online], p. C14. Retrieved September 30, 2014, from LexisNexis Academic database.

Son, S. (2012). Interview with Beverly Buchanan. Retrieved September 30, 2014, from «http://www.artanimalmag.com/beverly-buchanan/»

Stieber, J. (2013, June 24). Jock Truman and Companion: Nomenclature of the Closet. Archives of American Art Blog. Retrieved September 30, 2014, from «http://blog.aaa.si.edu/2013/06/jock-truman-and-companion-nomenclature-of-the-closet.html»

Syms, M. (2007/2014). The Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto. Retrieved September 30, 2014, from «http://martinesyms.com/the-mundane-afrofuturist-manifesto/»

The Chrysler Museum. (1992, June 18). Beverly Buchanan [Press Release].

Waddell, E. (1985, November/December). "Life...ain't been no crystal stair." Atlanta Art Papers, pp. 13-15.

Washington, B. T. (1895, September 18). Speech presented at The Cotton States and International Exposition. Atlanta, GA. Retrieved September 30, 2014, from «http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/39/»

Whitley, Z. (2013). "The Place is Space: Afrofuturism's Transnational Geographies." In N. J. Keith & Z. Whitley (Eds.), Shadows Took Shape (pp. 19-24). New York: The Studio Museum.

Wilderson, F. B. III. (2008). Red, White, and Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms. Durham: Duke University Press.

Notes

- My thanks goes to the following individuals for aiding in my research on Beverly Buchanan's time in Macon, Georgia: Park McArthur, Jennifer Burris, Jim Barfield, Jaime Webb, C. Terry Holland, Susan Welch, Carey Pickard, Virginia (Pickard) Templeton, Lucinda Bunnen, Jeff Bruce. My special thanks goes to Jane Bridges for her consistent communication with Buchanan during the writing of this article, and of course to the artist herself.

- In using the descriptive word "lumpen" to describe Unity Stones I wish to introduce one of its salient features, which is, that it is sited/placed in front of a community center that services members of the lumpenproletariat. In the Marxian deployment of this term (roughly translated in English as the "dangerous class") the lumpenproletariat is composed of various dispossessed peoples. But unlike Marx, who believed the lumpenproletariat incapable of aiding class revolution, Buchanan's lumpen forms are given the potential to be stations where revolution could be surmised, discussed, argued over, or ignored completely (Marx & Engels, 1906).

- Afro-pessimism is a still growing body of literature, but I refer generally to the work of Fred Moten, Saidiya Hartman, Jared Sexton, Frank B. Wilderson, Christina Sharpe, and Orlando Patterson, to think through the epistemological and ontological knots arising from blackness as a marked position.

- Although I only briefly mention Thing theory in relationship to Buchanan's workworkpractice, a fuller accounting is certainly called for.

- The 1978 Oxford English Dictionary defines "Ruin" as: "The act of giving way and falling down, on the part of some fabric or structure, esp. a building" (879), and later as "That which remains after decay and fall." The dictionary attaches ruin/ruination to persons, instutions, states, and material things. More dramatically, ruin can mean the "complete destruction of anything" as well as "The condition of [...] having been reduced to an abject or hopeless state."

- The whole passage is: "The ruin is not in front of us; it is neither a spectacle nor a love object. It is experience itself: neither the abandoned yet still monumental fragment of a totality, nor, as Benjamin thought, simply a theme of Baroque culture. It is precisely not a theme, for it ruins the theme, the position, the presentation or representation of anything and everything. Ruin is, rather, this memory open like an eye, or like a hole in a bone socket that lets you see without showing you anything at all, anything of the all" (Derrida, 1990/1993).

- Although it is not the exact topic of this essay, there have been a small number of responses to Afrofuturism as outlined by many of its adherents/practitioners. For example, Martine Syms suggests a Mundane Afrofuturism, which figuratively sets popular afrofuturist tropes ablaze in a "bonfire of the Stupidities." Sym's mundane afrofuturist is more likely to know what it is she won't do than what she will do, and thus is suffuse with a politics of negativity (Syms, 2007/2014).

- One of the best arguments for this is a statement from Cauleen Smith, whose interest in Sun Ra has often placed her in discourses around afrofuturism, who claims: "Afrofuturism as a practice, as a way of making and thinking means more than just naming a piece after the Gemini Space probe or some such. For me Afrofuturism centralizes formal considerations, structural considerations, and the stakes are in the praxis as much as in the language—if not more so" (Whitley, 2013).

But of course slavery was not just localized to the Georgia coastline, nor is it something merely geographical as Jared Sexton makes clear in "The Social Life of Social Death: On Afro-Pessimism and Black Optimism." After synthesizing the work of Orlando Patterson and Fred Moten, he wonders,

"We must still ask at this late stage, 'What is slavery?' The answer, or the address, to this battery of questions, involves a strange and maddening itinerary that would circumnavigate the entire coastline or maritime borders of the Atlantic world, enabling the fabrication and conquest of every interior-bodily, territorial, and conceptual. To address all of this is to speak the name of race in the first place, to speak its first word. What is slavery? And what does it mean to us, and for us? What does slavery mean for the very conception of the objective pronoun 'us'?" (30).

- Indeed, articles by Patricia Phagan and Charolotte Moore Perkins, two of the women Buchanan formed long-term relationships with, quoted later in this text provide some of the most personal and in-depth portraits of Beverly Buchanan. In Moore's text, the focus is on daily financial management of being an artist, and provides an account of what many of my contacts in Macon remembered about Buchanan—her savvy penchant for trading and bartering her works for needs. In Phagan's text, which is much more art historically pitched, the author asks the artist questions that others had yet to propose. Buchanan seems more candid in this interview, touching on subjects she rarely spoke about.

- Interestingly, this is also the situation with Buchanan's dealer Jock Truman, and the ethical entanglements of identifying, and thus particularizing the sexualities of subjects who don't cohere is given some interesting discussion by Jason Stieber, Collections Specialist at the Archives of American Art (Stieber, 2013).

- This is also around the time that Ad Reinhardt and Cecil Taylor (along with five other artists) have a heated exchange regarding the formal and socio-political dimensions of (seemingly) abstracted use of the color black in painting. This exchange is also, importantly, one of the objects of analysis in Fred Moten's "The Case of Blackness"—a text which gets circulated and discussed in relationship to ongoing discussions of afro-pessimism.

- I am thinking about place-naming as an extension of the argument made by Steven Hoelscher that "a full examination of American racial segregation must take into account the cultural productions that articulated it, reinforced it, and made it deeply embedded in daily life" (2003, p. 659). Thus the naming of a place is a performative geography of memory, articulating the cultural valences of race and place.

- This essay: six parts, bracketing two core concerns, circling around the historical-material experiences of Southern blackness, is meant to rhetorically rhyme with Buchanan's Unity Stones. It is to Beverly Buchanan that this essay is humbly dedicated.

Cite this Article

https://doi.org/10.20415/rhiz/029.e05