Shifting Aesthetics:

The Stick Up Girlz Perform Crew in a Virtual World

Jessica N. Pabón

Performance Studies NYU

AAUW Fellow

When I started graff in 1983, not many girls were involved in the game. [...] It changed over the last ten years. More and more girls got into the graff world, and after the STICKUPGIRLZ got more known and got their own website, I saw a lot of all-girl crews popping up everywhere. CANTWO, C.O.P. Magazine

[1] In 2000, the absence of any substantial representation of female graffiti writers was more than noticeable; it was as if, however unlikely, they simply did not exist. As a subcultural outsider, aside from a few nights of riding along and being a lookout for the guys, the bulk of my research was culled from canonical publications on graffiti subculture like Getting Up, The Art of Getting Over, and Subway Art. Academic and illustrative texts alike, consistently and uncritically marginalized, tokenized, and/or sexualized female writers, essentially erasing their presence in the culture's history. [1] Hoping to engage female writers through ethnography, I posted a call for participation on Art Crimes.org, the first graffiti-specific website on the Internet. Developed by Susan Farrell in 1994, Art Crimes was (and is) a well-known site with a vast amount of information and resources. [2] By 2004, not much had changed in the texts being published and my fieldwork efforts had resulted in a pool of research participants—about a half dozen women—that was still numerically misleading for an accurate accounting. In his 2006 photobook, Graffiti Women, Nicholas Ganz notes that the visibility of female writers in contemporary publications has incrementally improved, but the lack of representation remains deplorable. [3] As German writer CANTWO SUK (Stick Up Kidz), TMD (The Most Dedicated) notes above, something has changed over the last ten years that has had a dramatic impact on the number of active female graffiti writers and, more importantly for this article, on their presence within graffiti subculture. That something is the Internet.

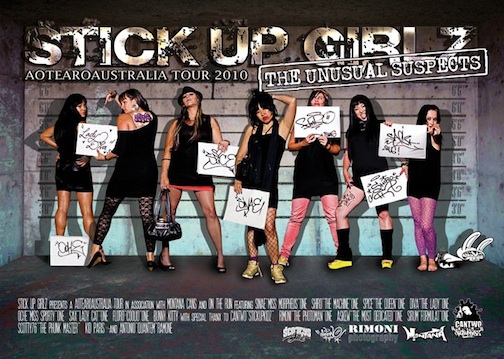

[2] The proliferation of graffiti websites specifically geared toward, focused on, and maintained by female writers is remarkable. Undoubtedly, the increase in visibility and the increase in female writers (all-girl crews "popping up everywhere") go hand in hand—a self-propelling phenomenon that I have witnessed with astonishment and excitement. The now-defunct site GraffGirlz.com, for example, offered many hyperlinks, an active discussion board, and a host of pages highlighting individual writers (see Figure 1). Each writer had her own page that included a biography, hyperlinks, photos of recent graffiti art, and sometimes, contact information. [4] Clicking my way through the site in 2008, I happened upon German writer SINAE's profile page where she had provided a link to her crew, SUG (The Stick Up Girlz). [5] Boasting members from Aotearoa/New Zealand (FLURO, OCHE, and LADY DIVA), Spain (SAX), Japan (SHIRO), and Australia (SPICE), SUG is a transnational crew that functions predominantly, but not exclusively, virtually (See Figure 2). [6] Founded in 2006, and often sponsored by Montana spray paint, the members of SUG have only physically convened three times: in Melbourne (2010), in Sydney (2011), and in Auckland (2012 tour). [7] Their web-based locale, a virtual street corner, is a place where these women can affectively come together despite geographical and temporal distance, somewhat sporadically, but always publicly and transnationally, to perform their belonging to the graffiti community and Hip Hop culture writ large.

Figure 1: GraffGirlz Screengrab

Figure 2: SUG Logo

[3] Representing the affective ties between you, your neighborhood, and your people is a consistently practiced, public aesthetic fundamental to Hip Hop culture. Lyrics, embellished clothing, and acronymic shout-outs on graffiti covered walls all signify belonging by announcing crew, by making claim to particular Hip Hop communities. The affective investment performed through crew membership is often described as an empowering relationship, a familial bond, a means of authenticating identity and proudly rooting oneself in a local community, in a "place." Performing belonging to place, grounds practitioners and maintains the impetus to stay connected to the local, as Hip Hop culture develops aesthetically and geographically. The contemporary phenomenon of membership in multiple, transnational crews, evidenced by SUG begs the questions: How does performing ties to multiple crews online and across national borders (thus publicly and transnationally) shift traditional conceptions of place in Hip Hop graffiti, a counterpublic (thus quasi-private) subculture? Further, what effects do these shifts have on the gender dynamics within graffiti subculture? By focusing on one such transnational crew, SUG, this article considers the impact on the presence of female graffiti writers when a counterpublic subculture makes itself accessible online, and when an aesthetic of locality goes global, virtually.

Performing Place in Hip Hop Culture

For me personally, Hip Hop is a big part of my graffiti and has had a huge influence on it, from the music I listen to, the style of letters or characters I draw, the colors I use etc. I also got into graffiti through my Bboy friends, and I've always been around a lot of the other elements of Hip Hop. In general I don't think graffiti is confined to Hip Hop at all nowadays, it's really its own culture. It is often linked back to Hip Hop in a lot of ways, and graffiti style is prominent in the other elements of Hip Hop—clothing etc, but it has gone so many other different ways, so many people that write graffiti are into so many different things and some really have no interest in Hip Hop at all. (FLURO) [8]

[4] The place of graffiti art within Hip Hop is a contentious matter, a debate produced by anxieties over artistic autonomy, notions of authenticity, and cultural community. When asked about the connection between Hip Hop and graffiti in an email, FLURO demonstrated this anxiety. For her, it is equally important to note the aesthetic and social dimensions connecting the two, while also respecting the autonomous developmental trajectory of graffiti art. Echoing this sentiment, b-girl and SUG member SHIRO (TDS, GCS, UZN), explained that yes, she considers herself part of the Hip Hop nation, but that graffiti is "an independent art" form. [9] Along with FLURO and SHIRO, SPICE (MC, b-girl, Hip Hop activist), OCHE, SAX, and SINAE all have a history and connection to Hip Hop culture that undoubtedly informs the way their crew was built, functions, and is maintained, as well as their individual stylistic choices (see Figures 3, 4, and 5). Each of these writers retains the tension produced by the ongoing, unresolved dialectic between graffiti and Hip Hop in a productive manner. The question of place and belonging is not a "problem" to be solved, but an indicator of what is at stake in defining community—who is in, who is out, who decides, and more importantly, why does it matter? In order to understand and recognize how the aesthetic of performing place and community is changing as graffiti subculture goes online, it is instructive to first explore how "traditional" performances of place and community have been theorized thus far in Hip Hop scholarship.

Figure 3: FLURO semi-wildstyle, Hip Hop character

Figure 4: SHIRO Boombox character with fade

Figure 5: SPICE boombox girl with bling and a Kangol

[5] Tracing the significance of references to the 'hood in Hip Hop's history, scholar Murray Forman argues that the 'hood is not only a vital location where identity is created and consumed, but also the place where artists can and must tap into for validity, energy, power, and authenticity. His book, The 'Hood Comes First, emphasizes that within Hip Hop culture, "space is a dominant concern, occupying a central role in the definition of value, meaning, and practice" (2002:3). Focusing his analysis on rap music, he argues that rappers simultaneously invest in and acquire affective value through calling out to their 'hood, whether it be Compton, or the boogie-down Bronx. Cognizant of the impoverished everyday living conditions and constant devaluation of the residents of these neighborhoods, Hip Hop practitioners take pride in place; they utilize the power of performative discourse to remake their 'hoods into places where people survive and sometimes thrive. Investing in their communities as centers of creativity, places of cultural worth, meaning, and power, Hip Hop practitioners resist sociopolitical subjugation by urban planners and politicians who have historically typecast (and developed) their communities as homogenous, anonymous ghettos. Performing community through rapping, an acrobatic verbalization, rappers delight in the specifications of the local.

[6] Writing specifically about the contemporary b-boy and b-girl scene in New York City, Joseph Schloss analyzes the performance of pedagogy. [10] In Foundation, Schloss focuses on the particulars of how this dance style is taught to locate the connections between practitioners and practice since b-boying's inception in the 1970s. Through an apprentice-like structure, a commitment to learning and contesting the proper names and originators of certain moves (that is, uprocking), and the repetition of specific songs (that is, Apache), b-girls and b-boys learn to perform their relation to Hip Hop history, place, and community. B-boying emphasizes, references, and connects to people and places through gesture. Performing the various moves, attitudes, and fashions (aesthetics which Schloss deems "foundations"), is a way to reach for, if not realize, "the promise of Hip Hop culture: that artistic power can be ideological power and that ideological power can be the key to creating a place in the world for themselves and their community" (2009:157). Complementary to Forman's argument that rappers utilize verbal references to validate local knowledge and take pride in their 'hoods, Schloss demonstrates how b-boys use gesture to reference the people and places in Hip Hop's history. As aesthetic strategies developed despite social and political invisibility, economic subjugation, and cultural devaluation, both rapping and b-boying demonstrate empowering ways of being that are grounded in public performances of community.

[7] Graffiti writing, the "visual parallel" to Hip Hop music and dance, also carries within its fundamental aesthetics this strong relationship to tapping into place, relating to your 'hood, and referencing back to your community for validation, empowerment, and creativity (Ferrell 1996:9). "Getting up" has always been about marking your presence, and in doing so, marking the existence of your affective ties on an otherwise dreary urban landscape designed to isolate, subjugate, discipline, and divide you (see Figure 7). One of the earliest examples of the performing place aesthetic in graffiti is the addition of numbers to a tag name as a way to reference a specific geography; the street a writer lived on or a notable area in their 'hood became a part of their graffiti identity. [11] The number(s) signified the place and the people to which that writer "belonged." The significance and utilization of numbers in this particular fashion has changed over time, but is still present. SHIRO often "tattoos" her Mimi characters with "BJ46" (see Figure 8). The "BJ" stands for "Big Jade," a deliberate reference to her Asian ethnicity, and the "46" is simply her "number," her "brand;" put together, "BJ46" means "Asian girl, Shiro, working global." Here, it is not the number performing place, but the letters—the hyperlocal 'hood is replaced with a desire to perform ties to her ethnic community as her imagery circulates transnationally.

Figure 6: DIVA and OCHE with b-girl character

Figure 7: SINAE Urban Landscape

Figure 8: SHIRO's "Mimi" character with BJ46 tattooed

[8] Surpassing the popularity of performing place through numerical locators (street numbers), performances of community in contemporary graffiti culture more often than not take the form of an acronymic "shout-out." A writer will shout-out to her peers and her crews by getting up for them. In Getting Up, Craig Castleman notes that the "saturation techniques and wide-ranging coverage" of one of the earliest groups formed specifically for graffiti writing, the Ex-Vandals crew from Brooklyn, produced a model for other graffiti writers. The Ex-Vandals demonstrated the positive attributes of crew membership: companionship, assistance with larger pieces, the availability of lookouts, and the capacity to get up via proxy (1982:105). Writers perform community through various stylistic alterations to the overall composition of the work (see Figure 9). It is not just her tag or her spot on the wall; she shares it with her crew by representing that crew publicly. Despite the undeniably individualistic qualities of the art form, any consideration of graffiti needs to consider the social aspects, for "even when they piece or tag alone, [writers] draw on the subculture's vitality and style—and on their sense of involvement with a larger enterprise—and engage in collective action" (Ferrell 1996:50). In his ethnographic work with the Denver, CO graffiti scene, Crimes of Style, Jeff Ferrell analyzes the relationship between community and style. Specifically mentioning Denver's "wall of fame" or "writers corner," he states that "[a]t the core of this collective activity were the locations where writers came to piece together, and in so doing to create collective bodies of work" (49). Part of acquiring artistic skills and attaining fame for graffiti writers is participating in, some or all of a variety of "collective" activities such as those mentioned by Ferrell, and at exhibitions, parties, and events. [12] The exchange of ideas and techniques at these events, combined with the competitive nature and bravado motivating writers, functions "to accelerate the technical precision and style of their work, [and] to create a sort of collective aesthetic energy on which they all draw" (51). Admittedly, not all cities have such meeting places, or host major graffiti events, and certainly not all writers have the means or desire to travel and/or participate in such public activities. However, there is one subcultural practice that every graffiti writer participates in that can happen anywhere, anytime—the exchanging of the piecebook. The piecebook is another place, not technically a geographic location searchable on Google maps, but a handheld and mobile environment where writers can participate in the production of their collective aesthetic energy. [13]

Figure 9: SINAE rainbow spectrum

[9] Hip Hop culture is fundamentally about individual practitioners embodying agency and having confidence in self-expression, performing self and community simultaneously. Because the aesthetic of performing place and community is so foundational to how Hip Hop functions and continues, it is important to mark the changes that occur when community is dispersed over the Internet and thus over the globe, and not simply because of commercialization and mass media, but principally by practitioners themselves. Different in physicality, but similar in purpose to a piecebook, a website falls "somewhere between sketchpad and archive" (Ferrell 68). Graffiti on a website also shares the characteristically ephemeral existence of graffiti on a wall—both are likely (and in some ways expected) to "disappear." The material mark and the virtual representation of that mark both leave traces, be they a mismatched paint patch meant to cover graffiti on a wall or the products of a Google search after a website has gone down. Ian Bourland rightly points out that "the vast majority of writers document and study their practice through DIY journals, websites, and piecebooks" (2007:78). The Internet has not replaced a marker and a clean piece of sketch paper, but is an added space where writers can practice, share, critique, and communicate with one another. The "collective aesthetic energy" of graffiti subculture is accessed and reproduced every time a graffiti artist writes herself or her crew into existence on a train, on a wall, in a book, or on a website. With the Internet at their disposal, contemporary female graffiti writers are shifting "traditional" performances of belonging in Hip Hop culture, historically dependent on local, physical connections. They challenge conceptions of community couched in the aesthetics of locality because these crews thrive both on the walls of cities across the globe and in the plethora of spaces available online. Using individual or group websites, social networking spaces, blogs, and online magazines practitioners travel from the material world to the virtual world and back again—leaving a trail of marks proclaiming their presence to the public.

The Stick Up Girlz

[10] What we now recognize as Hip Hop graffiti has been, since its emergence in the US during the late '60s, theoretically understood and practically performed as a subculture—below, less than, secondary to mainstream culture. Bourland, contesting the kind of graffiti that is valued within fine art institutions and archives, argues that the "range of interrelated techniques and interventions—what comes to mind when one is asked to describe graffiti—is public, clandestine, and aesthetic" (2007:60). Aside from the brief moments of social legitimacy gained by writers participating in the capitalist gallery/pop culture systems Bourland describes, the majority of graffiti writers are set apart from mainstream culture as a result of behavior deemed socially deviant, distasteful, and frequently illegal. Graffiti writers have very little opportunity to reformulate their social status or control their public image from a position of power. Add to that social dynamic the sexist connotations for women participating in a presumably male masculine subcultural activity, whereby because of their gender difference females are thought to be unable to perform on par, or felicitously, with their male counterparts. If the issue of visibility and presence for doubly subjugated female writers is actively addressed by their use of the Internet, we must ask how. How are female graffiti writers, active in a subculture established as counter to mainstream values, interacting with the Internet-using public, a decidedly global public made reachable through technology?

[11] Writing Publics and Counterpublics in 2002, Michael Warner speculates that "[o]ne way that the Internet...may be profoundly changing the public sphere [...] is through the change [it implies] in temporality" (68). No longer punctual but rather continuous, this temporal modification causes him to consider abandoning the conceptual usefulness of "circulation" in regards to the development of publics altogether. However, the modes, speeds, and shapes through which discourse circulates during the ongoing development of a public, remain useful ways to analyze the dynamics of online graffiti subculture. The continuous, almost always accessible circulation of discourse provided by virtual space invites participation and interaction with and by those who have historically been made inaccessible or invisible by the punctuality, authority, and power of large publishing institutions (those responsible for producing the canon)—namely, women. In response to his concern about the increasing "change in infrastructure" brought on by the Internet, we have to consider the detrimental effects that same infrastructure has had on the place, purpose, and value of female graffiti writers and their representation in the public sphere. In "E-scaping Boundaries," Emily Noelle Ignacio explores the ways that gender, race, and culture figure into building a nation when the "images of a nation" can be articulated by anyone through accessible technological advances as opposed to the authoritative power structures traditionally in charge of nation building. She claims that

Because the Internet is a transnational space where people from all over the world can converge, [scholars] can better examine how this kind of technology affects the construction of national, racial, ethnic, and gendered identities and can help create new coalitions apart from, rather than through the maintenance of, these socially constructed boundaries.

If, as Warner argues, how a text is produced and circulates informs the vitality and presence of a particular public, then it seems we should be less concerned with the stability of the infrastructure and more concerned with how the change in circulation allows the invisible to become visible, allows the marginalized subcultural participants to become the articulators of the culture. Creating and maintaining a website allows these countercultural "deviants" to control their image and manage the representations circulating about them—at least virtually. Further, it invites a larger audience to witness their performances of place and belonging.

The website is mainly to show each other and anyone else who checks it out who we are and what we've been painting...[i]t's also a good way for people overseas to contact us if they're coming to any of the countries we're in and want to paint. (FLURO)

[12] Visiting SUG's website, visitors are met with the crews' moniker "StickupGirlz," which tops the page in a style that mimics a drippy, sparkly, pink, yellow, and purple throw-up—a stylistic choice not strictly representative of each writers' repertoire, but a necessity as the medium (website) demands legibility (see Figure 10). The page also includes a "ticker" sidebar listing the latest image updates, a toolbar to navigate to additional pages (History, Members, Walls, News, Downloads, Links, Contact), and a series of boxes for joining their mailing list, reading the latest news and seeing the latest page updates. In case one wants to know, "Who are da STICK UP GIRLZ?" the "History" tab offers a brief cataloguing of events. [14] In 2003, SINAE was inspired by and taught how to write graffiti by her now-husband CANTWO, founder of the Stick Up Kidz crew (and clothing label). SINAE adopted and altered the name for her own crew, which has slowly but surely expanded since its inception. The discussion board (located under the news tab) makes the moment of foundation and expansion visible with an update from SINAE dated 3rd August, 2006: "finally our site is online and my crew has grown...hehe, welcome OCHE and LADY DIVA...my family and friends beyond graff." [15] You can "choose your favorite writer" and easily navigate to her personal page complete with a profile indicating country, year of birth, length of time writing graffiti, length of time representing SUG and any additional crews, link to her individual website, sometimes an email, a brief biography, a date stamp of her last update, and in the case of OCHE, a photo (which is unique for a culture balancing legality concerns and dependent on anonymity). Alongside this biographic information are a variety of visual markers: the writers' tag or throw-up, the latest images uploaded, a sampling of productions, canvas work, and sketches (see Figure 11).

Figure 10: SUG Homepage screengrab

Figure 11: OCHE writer's page

[13] SUG's website offers the visual and linguistic discourse of graffiti subculture but does so in an atypical way—they mark their gender difference. "[A]ll discourse or performance addressed to a public must characterize the world in which it attempts to circulate, projecting for that world a concrete and livable shape, and attempting to realize that world through address" (Warner 2002:81). The central figure on the homepage is but one example of how SUG "characterizes the world" they want to circulate, the public they want to create. The image is of a young woman with blueish-black hair and olive skin. With spray paint can in hand, she is fit with sneakers and a "feminine," but not hyper-sexualized, one-piece jumper. She has an air about her, read in her stance and facial expression, that she has just made her mark somewhere in the urban background—the illegality of that act signified by the gang of search-light helicopters closing in behind her. Choosing to make this character the "face" of their crew, SUG maintains a countercultural tone that produces the kind of discourse that goes beyond being "different or alternative [...,] but one that in other contexts would be regarded with hostility or with a sense of indecorousness" (Warner 2002:86). Transgressing gender roles, legal boundaries, and safety concerns, SUG's representative stands on a riverbank with one foot propped on a skull and bones; she doesn't look too concerned and her confident posture assures that we are not concerned for her either.

[14] The continuous circulation of SUG's imagery moves among strangers surfing the net and brings them together through a shared interest (longstanding, newly developed, or somewhere in between) in the kind of visual discourse provided by the website. By putting SUG online and inviting the virtual public to participate in circulating their work and words, the members cast a wide net to attract participants. The presence online certainly casts a net to potentially attract strangers, but the aesthetic and legal issues inherent to graffiti culture are equally effective at keeping unwanted strangers at bay (those who simply do not appreciate graffiti will not participate). Producing their own online space not only supports "[t]wo of writing's key elements—technical virtuosity and its publicity-generating function," but also exaggerates those elements through virtual reproduction (Bourland 2007:67). In the oft-quoted but endlessly instructive text Imagined Communities, Benedict Anderson reminds us that "all communities larger than primordial villages of face-to-face contact (and perhaps even these) are imagined. Communities are to be distinguished, not by their falsity/genuineness, but by the style in which they are imagined" (2006:6). What is the style of the visual discourse that signifies this particular public as it circulates among, and hence produces, a virtual public? What is the mode of address? In graffiti culture, that style is decidedly and paradoxically counterpublic; graffiti "writer's meaningful and unique artistic practices were developed [in the U.S.] on the trains, illegally, performatively, and non-commercially" (Bourland 2007: 67). The fact that graffiti is a criminalized subculture affects questions of accessibility and approachability. The last tab on the SUG website's toolbar, "Contact," makes this reality highly visible by warning visitors that "www.stickupgirlz.com is only documenting what's out in the graffiti scene, and is NOT in any way advocating for anyone to do illegal stuff." In other words, you can participate on the website, but if you choose to participate in the physical world, by doing graffiti of your own, SUG wants you to remember that in most countries there are social and legal ramifications to such actions; "[o]ne enters at one's own risk" (Warner 2002:87). Representing themselves through their homepage character, SUG maintains their countercultural flair as they present themselves to, and develop, their virtual public.

[15] In order to make a claim to public space, writers have always had to develop strategies for keeping their identities confidential and within the community while simultaneously putting their identities out for the world to see. Wildstyle exemplifies the ongoing anxieties of being a public art form that values privacy (See Figure 12). The SUG website (until you click on individual images) does not utilize wildstyle in order to keep the virtual public out and is, in fact, highly legible, highly accessible. The change in where and how graffiti culture is made and makes itself accessible to the public is an interesting effect of performing community and crew online. The legibility provided by the style of their presence satisfies the critical need to address the public, but here, the public being addressed by the counterpublic is a virtual one. On a city street, the public is denied a level of access to participation, which in turn produces and maintains graffiti as a kind of private-counterpublic. For most strangers to graffiti culture, the writing on the wall fades into the urban landscape, has no direct relation to them, and becomes something they are not necessarily a part of. In contrast, when present online, the level of access and the opportunities for engagement with graffiti culture increases due to the way websites function, in general (you can click, save, share, tweet, like), consequently producing it as a kind of public-counterpublic.

Figure 12: SPICE representing the Universal Zulu Nation, an international Hip Hop organization founded by Afrika Bambaataa devoted to the betterment of all oppressed peoples.

[16] The conversations posted on SUG's news discussion board, for example, are not directed toward strangers per se—they are directed from one writer to another, but the news and discussion also address an imagined public, which is then shaped through the Internet users' desire for access to the conversation. By virtue of being a website not restricted by passwords or limited user-friendliness because of aesthetic choices, their site is open to the participation of strangers. The line that keeps nonmembers out of direct access and at a safe distance is here managed by allowing only crew members access to changing or updating the content. Surely, not everyone cares to see SUG's latest production, or to know that they are meeting soon, or that they are "still rockin'," but the potential that someone out there does care and will respond by clicking themselves into participation is implicit in the crew's desire to share that information publicly. The notable increase in the presence of graffiti culture online signals a desire by some to take hold of the virtual public sphere, mark their countercultural presence, and make transnational connections despite the disposition of keeping it local, keeping it quiet, and keeping it private that illegal activity often demands.

[17] Online participation is an ever-changing procedure of how, when, why, who, and how often the Internet user is clicking into the crew's virtual place. "The existence of a public is contingent on its members' activity, however notional or compromised, and not on its members' categorical classification, objectively determined position in social structure, or material existence" (Warner 2002: 61). Cyberspace is where one goes to participate in this public, whether one is a member of the SUG crew or not. For Warner, these strangers become part of a public by performing (acting, participating), not by being (of a certain demographic). This distinction is crucial to understanding the effects of graffiti culture's online presence in relation to the virtual strangers who may or may not enjoy the correct "categorical classification" or "position in social structure" that would enable them to participate freely in the male-dominated space of graffiti subculture.

[18] To allow for the changes made in notions of privacy and publicity and performances of community and belonging when graffiti culture goes online, we have to expand the boundaries of relation and participation. Warner guessed correctly that one of the effects the Internet would have on publics was a temporal one, but it has also affected a change in spatiality. [16] One of the primary ways the aesthetics of place are being shifted when graffiti culture goes online is the manner in which a "strange" public is engaged, given access, and invited to participate as a virtual public. The private counterpublic becomes a public counterpublic when it performs its countercultural deviance online. This is fundamentally different than the ways we are used to thinking about place and connections being made up of close, intimate (hence private) relationships with people who are anything but strangers. With a sense of what is being presented to the virtual public, we can now ask what this website does for SUG. How does performing public deviance in a technologically mediated fashion build community, make place, and shape group and individual identity?

[19] Unsurprisingly, writers express both the positive and the negative effects of graffiti being online. Interestingly, both "sides" of the argument have to do with exposure. SPICE points to one negative aspect of instant communication and availability when she says that "meeting a pioneer from New York [used] to be like 'Ohmygod.' Now any kid can hit'em up on Facebook" (Jarvis and Alvarez 2011: 37). In SPICE's estimation, the excitement of coming across something or someone unexpectedly has been replaced with an assumption of finding who or what you are looking for online. An "old school" Hip Hop head from the 80s, she admits that her viewpoint stems from her pre-Internet experience. Within her nostalgic "negative" there is a testimony to the ease, relative accessibility, and intensified usage of the Internet (and related contemporary technologies) to communicate across local and national borders enabling graffiti writers to connect. With less than a decade of writing at her fingertips, FLURO expresses an alternative viewpoint:

I have another local crew I represent, FDKNS. It's pretty different from SUG, mostly because I see the other crew members all the time [...] It's cool to be part of an international crew, you get to see a whole lot of diverse styles and see what's going on in the other countries. I'm lucky to have members of both crews to paint with in the city I live in and also the opportunity to travel and paint with crew members overseas. (FLURO 2009)

FLURO claims belonging to two crews, FDKNS (Forever Def Kings [Kweenz] Never Surrender), her local co-ed crew in Aotearoa and SUG (Stick Up Girlz), her transnational all-female crew (see Figure 13). She explained that graffiti writers are utilizing the mobility enabled by technology to develop creative and affective ties to multiple peoples and places. For SAX (of SUG, HEM, RS, Mp3), graffiti writers using the Internet is "the future! Some years ago we only had contact by writing letters sending photos etc....but now you are millions of photos with one click and contact with all [the] world['s] writers." [17] Rooting themselves in several communities produces a more expansive sense of belonging and provides opportunities to keep in touch with stylistic trends, both at home and abroad.

Figure 13: FLURO Ninja Turtle piece with FDKNS and SUG prominently displayed.

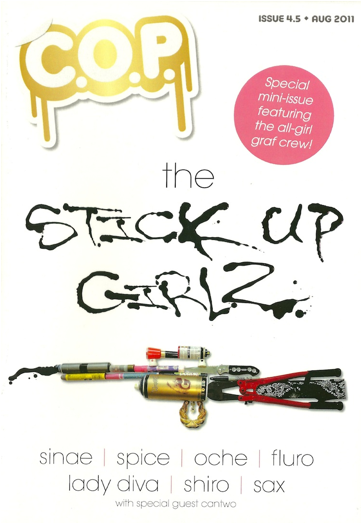

[20] Gill Valentine explores the effects of globalization on contemporary modes of "doing family" and argues that the "doing" is increasingly being done (predictably) on the Internet. In her article, "Globalizing Intimacy: The Role of Information and Communication Technologies in Maintaining and Creating Relationships," she expands the general assumption that intimacy requires physical proximity and asks her readers to consider how the Internet alters the boundaries of intimacy and affect in general (2006: 367). As a relatively accessible medium it "provides a new space for maintaining intimacy," it "expands the opportunities for daily meaningful contact" beyond physical bodies which in turn "can also facilitate the creation of new intimacies" (369, 370, 378). While my analysis is not focused on "doing family" or "doing sexual intimacy," it is about "doing crew" and how that "doing" is changing through the Internet within the context of globalization. Further, crews are more often than not described as family, alternative and chosen family. In a 2011 interview with C.O.P. Magazine, SINAE echoed this sentiment. In response to the editors prompt, "I guess the crew must be pretty tight then, they must feel like family to you," she responded "Yeah. We are like a family, it is like that" (7).

[21] Following Arjun Appadurai's conception of globalization, Valentine notes that it is "a complex process of movement and flows of people—as well as goods, services, capital, technologies, ideologies, and so on" (367). Contrary to the distance implied when one thinks of relationships across nations, the shift from hyperlocal to transnational crew formation is not one that takes practitioners away from their well-built commitments to place and community. Performing ties across borders is a possibility because these writers are supported by virtual communication technology like texting, emailing, video chatting, and social networking which are unbound by the time and space limitations of materiality. It is important to remember the affect that flows within and alongside these bodies, technologies, and ideologies; feelings and senses exist despite the rapidity of flows and the corresponding sporadic and perhaps partially fractured relationships. Similar to the relationship between a website and a piecebook described earlier, the connections made online do not replace physical day-to-day relations, but rather act as affective scaffolding supporting the established and developing new relationships. As FLURO noted in her interview, "I met the N[ew] Z[ealand] SUG's in person and thru them met the other crew members, but a lot of people use the net to check out someone's work or initially meet contacts in other countries" (sic). She elaborated, "the Internet has definitely played a role in creating [SUG], I think some of the other members met first thru the Internet. [SUG] is all over the world, so the current crew haven't ever all got together yet!" (sic). The website minds the gaps between the physical encounters; it provides additional adhesives joining the participants who make up the crew in a world where we are otherwise torn apart in various ways by distance, mobility or immobility, and the conditions of postmodernity—fracture, individualism, and alienation.

[22] Because websites can go up and down in the blink of an eye, and because these relationships between crew members are made on the Internet (and thus have a lingering "less-than real" quality about them), I asked FLURO about longevity. What contributes to a crew maintaining itself? What threatens longevity? For her, "[i]f crew members are good friends and the crew is supportive and involves everyone in various projects it's likely to last....The main contributor to a crew's longevity is if they become a whole lot more than just a bunch of people that paint together, if they become more like a family." The rest of SUG echoed this sentiment individually when C.O.P. Magazine editors inquired about SUG's collective make-up. According to crew founder SINAE, SUG became more than a one-woman endeavor during her initial travels to New Zealand in 2003, when she befriended LADY DIVA (the first female writer she had ever met). Now, as a crew of seven, the "friends first" mentality remains (Jarvis and Alvarez 2011:7). SINAE explains that "Crew = Unity and fam[ily. You] can show and produce way greater things in a group, it has a big and powerful vibe." [18] For her part, when asked about her artistic inspirations, LADY DIVA cites her crews (SUG and TMD) and interchanges the "friends first" language with the language of family: "they truly inspire me all in different ways and they are family in every way" (15). OCHE, of SUG and TMD, attributes the strong focus on family in her crews to the cultural influence of the Maori: "It's an extended-family-type-vibe which is normal among many Pacific Islander families" (17). When it comes to her all-woman crew, SAX is confident and optimistic that SUG is here to stay: "I hope the crew will last forever ;), I believe in the girls." The members of SUG all utilize the rhetoric of family in describing their relationship with one another, the "powerful vibe" of the crew, but theirs is a family of individuals born across oceans. SINAE noted that they "are all good friends even [though they] come from different countries, different backgrounds and different nationalities...[they] need a lot of tolerance and patience. But the key is that [they] are first friends before [they] are crew members and that [they] all share the same love for graff." SUG is not related by biology but by choice, by affect—a shared love for graffiti art and a shared commitment to each other.

[23] In Valentine's discussion of "doing family," she notes that "[t]ransnational families can be defined as families who are physically divided between different nation-states but maintain close contact" (375). She then goes on to consider "families of choice," a phrase borrowed from queer theory, to consider the alternative modes and structures of closeness and intimacy created. [19] A cursory look at the news board demonstrates SUG's development as a kind of transnational family of choice; the ever-evolving familial relations between these writers is announced, developed, and maintained via the Internet until the next time they can meet up. On 10 June, 2009, SINAE posted: "Welcome our latest new crew sista FLURO from Aotearoa... XOXO;" on 6 October, 2008, LADY DIVA posted: "A few new uploads, hope all my SUG family are great...hi everyone!!" and SINAE, again, on 13 September, 2008: "Hey... I want to welcome SPICE from Australia to the SUG fam...Love you all and keep on rockin." [20] The news/discussion board is not only a place where SUG develops their family of choice, but it is also a site for performing their love, care, and support of one another publicly.

[24] By building an all-female crew in a manner which makes the individual writers and the crew as a whole visible to the public, SUG is proclaiming something about the potentiality of familial ties between female writers that is, to this day, a unique phenomenon. Against a hailstorm of sexist stereotypes portraying women writers as isolated, unmotivated visitors to graffiti culture, SUG provides a counter image of the female writer, a non-hating, hard-working woman in a group of women of equal tenacity (see Figure 14). Not expecting to be "put down" with SUG, FLURO explains that she "had another crew already [FDKNS], which was mostly guys, so [she] was really stoked. The girls are so cool, they're each really individual people. It's cool to see girls that actually do stuff. 'cause there's tons of girls that don't 'do' anything" (Jarvis and Alvarez 2011: 27). Having a space where members can post (it is not a public discussion board where random strangers can add their opinions) enables the exchange of the day-to-day information that keeps people connected. For example, LADY DIVA announced on 7 October, 2006, "Finally a new piece to upload, 7 months pregnant & still goin!" and soon after, OCHE responded with: "Just over a week old, Michaiah Williams, newest addition to Lady Diva's kiddies. Congrats!" There are also birthday wishes, a plethora of encouragement and feedback on posted images noting the "beauty" and "great work" that make for "candys for [their] eyes" (sic). FLURO mentioned the ease of attending to the obligations that come along with being part of a crew, and added that "we have email mostly to contact each other and we upload the photos of what we've been doing so the other crew members can see what we've been painting etc." Existing mostly in their virtual place over the past six years, barring the three meet-ups thus far, the transnational crew has been successfully maintained. SINAE makes it a point to note that she met all the SUG members in person before inviting them to join the crew; it is the members living outside of New Zealand who met each other online. When the entire crew stayed with SPICE during their 2011 meet-up, she felt that they were finally able to get "to know each other properly. [...] It brought [them] all together even more" (Jarvis and Alvarez 2011: 35). The value and association between the face-to-face encounter and propriety/closeness remains, but SPICE's addition of "even more" signals the value of the virtual encounters.

Figure 14: SUG 2010 Tour sponsored by Montana

[25] Building, maintaining, and reproducing your crew in a transnational context by way of the Internet, restructures modes of intimacy, affective ties, and family. SUG, a crew that began as "just a friendship thing" according to SINAE (Jarvis and Alvarez 2011: 7) is but one example of how the boundaries of these terms, and performing them, are stretched and thus make room for "doing crew" in more expansive ways, less restricted by habitual, socially, and individually imposed barriers. "To tell you the truth," SPICE admits,

[A]lthough I was really honoured, I don't believe you have to be a crew to do what you do. I tend to paint with more people that I'm not in a crew with. And to paint with a bunch of girls was a little bit daunting for me. But now that we've all met up and really bonded, I love it. I love the name. I love our individuality. A lot of crews have people from everywhere, but they don't get together like we do, so we've got some good shit going on with that. (Jarvis and Alvarez 2011:41)

[26] Writers can work locally and by posting the image on a website, a virtual street corner, they can represent globally—it doesn't mean any less, it just means differently. If we consider the guiding mantra of graffiti—put your name and your people's names up as much as humanly possible—then this new way of circulating those representations becomes yet another vehicle for the proliferation of this counterculture's presence. If crew membership fosters support, inspiration, and a challenging creative environment, then it is clear why "there are a lot of multi-national crews" using the Internet, alongside their travels, to make "connections...all round the world" (FLURO). Writers are actively embracing the benefits of investing time and care into the endeavor of doing crew virtually and transnationally.

[27] The point here is not that the website is, as Valentine argues, "producing fundamentally different types of family behavior but rather" that through Internet communication technologies we witness "a reordering of habits, routines, and relations" (2006: 387). The reordering of habits, routines, and relations because of graffiti culture's online presence manifests itself by challenging the patriarchal order, breaking down sexist boundaries, and building new relationships amongst those formerly marginalized writers. Here, we must consider the effect of this reordering on gender dynamics within graffiti culture and Hip Hop culture broadly, where gender stereotypes position women as incapable of performing on par, or felicitously, with their male counterparts. Taking into account the dramatic shift in numbers I noted at the beginning of this essay, it seems that, indeed, "[w]omen, in particular, apparently regard the Internet as liberating, allowing them more opportunities in relative safety to experiment and take [...] risks beyond their expected gender role" (Valentine 2006:372–73). Whether presenting their crew online is a move to claim and create place that is specifically feminist in intent is, admittedly to my chagrin, beside the point. When SINAE calls to her crew to "[c]heck our latest ladypower-production," it is more than likely that graffiti writers outside of SUG, not to mention those individuals puttering around the virtual public, are going to heed the call and check out the image. Not only does this seemingly simple statement provide support and encouragement, but it also promotes and markets their subcultural labor beyond the immediate boundaries of their crew. The call invites new connections made through the recognition of their work.

[28] The space provided by the Internet is clearly one that is being used to reach out, to take advantage of the possibility of connections across a host of boundaries—national, cultural, lingual, gendered—that can make visible the work and value of "those traditionally excluded from public space" (Valentine 2006:378). The space that these women have been, and are, excluded from includes not just their own cultural space within graffiti subculture, but also the public space that frames them (especially "bombers" working illegally) as social deviants; theirs is a double exclusion. Sexism in graffiti culture has and continues to condemn women (in ways both tacit and obvious) to a second place position, and disciplinary moralism in legislation and urban planning casts them away from and out of the public space (quite literally, by putting them into jail) reserved for productive, law abiding citizens. Through the Internet, SUG developed a transnational virtual 'hood which offers those who might be marginalized at the level of the local the possibility for connections across those borders that otherwise keep them isolated. Seclusion is a state of being that feminist scholars, myself included, have long argued is endemic to the lack of representations of women, a byproduct of a lack of recognition and public visibility. The lack of representation and recognition takes place in specific locales (whether they be published works, gallery spaces, or street corners)—it is produced spatially, and as we are seeing with the Internet, so is the corresponding response.

[29] The place produced by the SUG website functions beyond conceptions of the 'hood that stress connections to the local as an imperative for creative and social value, but it is still rooted in the values and function of performing belonging to and a place within the 'hood. In the anthology Place and the Politics of Identity edited by Michael Keith and Steve Pile, the authors stress "the connections through space and the corresponding links between places and peoples [...] in which the bonding of different experiences through their spatialization displaces the common implications of exclusion that the geography of communities can imply" (1993:18). If, for women in Hip Hop (and women in subcultures, generally), the relationship between male masculinity, participation, gender privilege, and authenticity has historically excluded their participation, it is particularly important to recognize how this boundary is traversed through new relationships to place, through participation and process made available online. Connections, in this context, do not emerge only from the "inside" of a community; the seeds of these roots are planted when other writers respond to the invitation to connect, to share, globally and virtually, in this place that they have created on their website. These roots are simultaneously local and transnational and the Internet is the mediating apparatus that allows this process to happen. Even if it is "just" that the Internet allows these women to make a place of their own and connect over a multitude of boundaries, considering the context, this is nothing to scoff at. The Internet allows continued access to women who, if they might otherwise not have the ability to be supportive and participate in person, at least can stay connected virtually. Affective investment in performances of community remains as this counterculture goes online, but remains differently in ways that are critically important for the validity and presence of female writers (or other disenfranchised would-be participants).

[30] For FLURO, "[c]ommunity is a group of people who share and encourage and motivate each other to achieve individual and common goals." Community is an active process of investing self, reaching outward and inward; it is a process of sharing not just physical space but affect, and affect can take place in person or online. Focusing on mode of participation and process of performing community, for Keith and Pile, is a way "to move away from a position of privileging positionality and towards one of acknowledging spatiality" (1993:34). Focusing on the how and where of performances of community displaces the weight of identity and notions of authenticity that limit access to belonging. The politics of identity and the politics of place are here actively challenged whenever a connection is made outside of, or rather in addition to, the "traditional" composition of community within Hip Hop culture when a virtual public is brought into the fold. As for SUG, we might think about the strangers who are attracted and inspired by the presence their website provides. They are female writers, they have their own crew, and they are there for one another across national boundaries, bound by affect and aesthetics and unbound from the limitations of traditional gender roles which have historically removed them from both the public and the counterpublic spheres. [21]

Shifting, Not Breaking

I am very happy and proud to be a SUG, it represents all my graffiti life, because when I started to paint, there were no girl crews, just one or two that only painted with their boyfriends sometimes. [...] So when I see a girl who wants to start, I am very happy and I try to help her and paint with her. To be in SUG with other women representing is great! It's a dream come true. (SAX in Jarvis and Alvarez 2011: 45)

[31] The shift to the Internet is definitively reordering the dynamic of participation and visibility for female graffiti writers. With the availability of the Internet, female graffiti writers are not only performing their countercultural identities and demonstrating their belonging, but they are also building and sustaining their communities and crews through the openness enabled precisely by the technology itself. The changes outlined in this essay are not intended to imply breaks with foundational Hip Hop aesthetics. The changes are most accurately described as shifts, cumulative improvisations that carry with them traces of what came before as they move along, made by a culture founded and grounded in this most important survival skill. The shifts discovered here are: graffiti culture moving into a more publicly accessible (yet, still counterpublic) domain as it increasingly exists online; the remarkable increase and maintenance of female writers' access to and presence within the culture; and the discourse of place itself, now slightly removed from the hyperlocal, reconfigured away from "traditional" notions of authenticity rooted in identity and into those rooted in performance and participation. These shifts, importantly, are not clean cut for there are certainly issues of basic Internet access to consider, not to mention the less immediate "leisure" time common to Internet usage of this kind. Taken together, the shifts noted here are profoundly important, particularly for female writers or other disenfranchised would-be participants who might not fit into the heterosexual male masculine mold retrofitted to definitions of Hip Hop culture's authentic make-up. [22] The aesthetics of performing place are maintained whilst being expanded and refigured by various practitioners around the globe. SAX's "dream come true" and SUG's subcultural impact are harbingers of more shifts to come at the hand of female graffiti writers performing transnational crews in virtual spaces (see Figure 15).

Figure 15: SUG received their own feature issue through C.O.P. Magazine, a prominent and growing graffiti magazine written by, for, and about female writers out of Australia.

References

Anderson, Benedict. 2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London, New York: Verso.

Anon. 1971. "'Taki 183' Spawns Pen Pals." Taki183.net. «http://taki183.net/_pdf/taki_183_nytimes.pdf» (Accessed 27 November 2009).

Graff Girlz. "Graffgirlz & Catfight." Graff Girlz. «http://www.graffgirlz.easyforum.fr».

Stick Up Girlz. "STICK UP GIRLZ." «http://www.stickupgirlz.com».

Bourland, Ian. 2007. "Graffiti's Discursive Spaces." Chicago Art Journal, 56–93. «http://ianbourland.typepad.com/files/graffiti.pdf» (Accessed 22 January 2012).

Castleman, Craig. 1982. Getting Up: Subway Graffitti in New York. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Cooper, Martha, and Henry Chalfant. 2002. Subway Art. Reprint. New York: Holt Paperbacks.

Ferrell, Jeff. 1996. Crimes Of Style: Urban Graffiti and the Politics of Criminality. Boston: Northeastern.

FLURO. 2009. "Email Interview with FLURO." Interview by Jessica Pabón.

Forman, Murray. 2002. The 'Hood Comes First: Race, Space, and Place in Rap and Hip Hop. Middletown, CT.: Wesleyan University Press.

Ignacio, Emily Noelle. 2006. "E-scaping Boundaries: Bridging Cyberspace and Diaspora Studies through Nethnography." In Critical Cyberculture Studies, eds. David Silver, Adrienne Massanari, and Steve Jones, 181–93.

Jarvis, Erika, and Ivee Alvarez. 2011. "C.O.P. Special Mini-Issue: The Stick Up Girlz." C.O.P. Magazine 4.5.

Miller, Ivor. 2002. Aerosol Kingdom: Subway Painters of New York City. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Pile, Steve, and Michael Keith. 1993. Place and the Politics of Identity. New York: Routledge.

Powers, Stephen. 1999. The Art of Getting Over. New York: St. Martin's Press.

SAX. 2012. "Email Interview with SAX." Interview by Jessica Pabón.

Schloss, Joseph G. 2009. Foundation: B-boys, B-girls and Hip Hop Culture in New York. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

SHIRO. 2009. "Email Interview with SHIRO." Interview by Jessica Pabón.

SINAE. 2012. "Email Interview with SINAE." Interview by Jessica Pabón.

Valentine, Gill. 2006. "Globalizing Intimacy: The Role of Information and Communication Technologies in Maintaining and Creating Relationships." Women's Studies Quarterly 34 (1/2): 365–93.

Warner, Michael. 2002. "Publics and Counterpublics." Public Culture 14 (1): 49–90.

Notes

[1] This article is taken from the last chapter of my dissertation, "The Art of Getting Ovaries: Female Graffiti Artists and the Politics of Presence in Hip Hop's Graffiti Subculture." The introduction includes a comprehensive literature review of the canon to which I reference briefly here.

[2] The ease with which sexist assumptions about graffiti subculture become naturalized and internalized—even for a feminist scholar—was made more than evident to me as I waited for a response from the Webmaster of Art Crimes. My own complicity in the system of gender biases came to light alongside the utter surprise I felt when the response came from Susan.

[3] His mostly illustrative book is still, at the time of this writing, the sole publication that focuses on women. Important to note, however, is that this text was produced as an afterthought to his Graffiti World, has a predictably hot pink theme, and lacks analytical engagement with the artists—leaving a lot to be desired.

[4] In contrast to a website like Artcrimes.org (where, unless you know the name of the writer for whom you are looking, cold research for a specific "demographic" is nearly impossible), GraffGirlz was specifically a site for "graffiti girls;" that gesture in itself eliminated a lot of problematic guesswork.

[5] GraffGirlz was launched in October 2005 and taken down sometime in 2008. The online publication CatFight Magazine joined with GraffGirlz to create a forum (http://graffgirlz.easyforum.fr) in 2007; the forum has 472 registered users at the time of this writing. Also worth noting is that GraffGirlz has many successors. KIF, a writer from León, Mexico designed and manages www.ladysgraff.cjb.net, www.ladysgraff.blogspot.com, and the "secret" invite-only Facebook Group "Female International Graffiti" which at the time of this writing has 288 members. Most writers use MySpace and Facebook, have their own websites (more so if they are doing legal work only and/or design work), keep an updated Flickr account, and some have taken to blogging.

[6] There is one "member" of SUG, BUNNY KITTY, who is not actually a member but appears on the site as a joke. BUNNY KITTY is a female character painted by PERSUE, a male writer. Also of note, SAX does not yet appear on the crew's website.

[7] To see a short video on their 2012 Auckland tour visit «http://vimeo.com/12013572».

[8] All FLURO quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from our 28 October, 2009, email interview.

[9] All SHIRO quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from our 25 October, 2009, email interview.

[10] Despite my longstanding concerns about the gendered nature of Hip Hop vernacular, I will use the term "b-boying" instead of the gender neutral "breakdancing" for two reasons: the text I am referencing uses it and it is the preferred name for the dancers themselves.

[11] The popularization of this aesthetic is often attributed to TAKI183, a writer from Washington Heights who worked as a bike messenger. In 1971, the New York Times made his tagging efforts well-known and sited some of the "pen pals" he was inspiring (i.e. Barbara 62) as he wrote his name across the surfaces of any and every stop along his route.

[12] A few major events that happen at least annually: Chile's ConceGraf, Meeting of Styles (separate international events), Art Battles (NYC and abroad), and Art Basel (Miami, FL).

[13] There are a variety of names for the sketchbooks, usually those black composition sketch books you can get at any art store, and the name just depends on the location. In Boston, they were referred to as bibles, in New York they are blackbooks and for Ferrell in Denver they are piecebooks.

[14] The "Stick Up Kidz" website is practically a mirror image—through formatting and layout but not color/gender codes—of the SUG website. The SUK page is grey, white, and black with male figures where there are female images on SUG's site. One can only assume whoever designed the SUG site also designed SUK's site—or vice versa.

[15] Unless otherwise noted, all quotes pulled from the SUG website www.stickupgirlz.com were accessed on 25 November, 2009. Very little has been updated since then.

[16] The effects on temporality are produced in tandem with the change of graffiti's ephemerality. The timestamp or date of creation doesn't "matter" online, graffiti lingers and is always in the now past its materiality—always already circulating outside of the limits of "material" time and space.

[17] All SAX quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from our 14th February, 2012, email interview.

[18] All SINAE quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from our 1st February, 2012, email interview.

[19] Valentine cites Lauren Berlant and Michael Warner: "'[m]aking a queer world has required the development of kinds of intimacy that bear no necessary relation to domestic space, to kinship, to the couple form, to property, or to the nation'" (378).

[20] Emphasis added.

[21] At the time of this writing, I posted the question "How many of you belong to a crew that is transnational? (For example, SUG has members from Germany, Australia, Japan, Spain, etc.) And what about all female crews?" to the Facebook Female International Graffiti group. I received one response from Maripussy Crew (Peru, USA, Spain, France).

[22] I say retrofitted because there is clear evidence that Hip Hop was not a solely heteromasculine enterprise in the beginning, but made to look that way over time.