The Underbelly Project: Hiding in the Light, Painting in the Dark

Jeff Ferrell

Texas Christian University, USA, and University of Kent, UK

[1] A few years ago, New York City street artist and artiste provocateur PAC was out doing what street artists sometimes do: drinking. As the night wound down and the drinks added up, a guy PAC had met earlier in the evening asked him if he wanted "to go somewhere cool." PAC soon enough found himself in a cavernous, never completed, long-abandoned New York City subway station, four stories below street level. "I woke up the next morning feeling like I might have dreamt it all," PAC remembers. But it wasn't a dream. It was the beginning of what was to become the Underbelly Project.

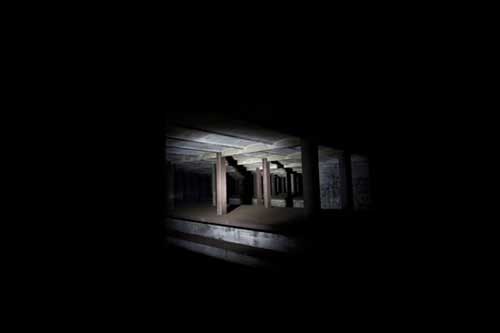

Fig. 1. The Underbelly Project.

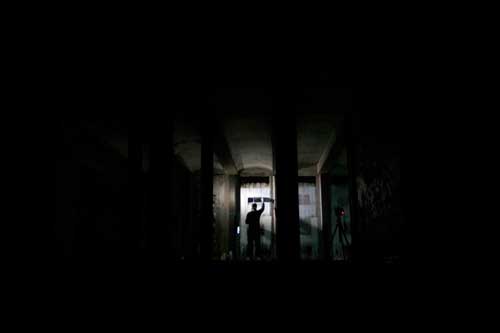

Fig. 2. The Underbelly Project.

Fig. 3, 4, 5. The Underbelly Project.

[2] Over the next three years, PAC would visit the space off and on, digging the darkness and the old architecture and the sprawling underground space. Then, one night, the invitational process repeated itself. Running into New York City street artist and gallery artist Workhorse at one of Workhorse's gallery shows, PAC told him, "I see you like abandoned spaces in your artwork; I know a place that you might like to photograph." A week later, while visiting the station together, PAC and Workhorse decided on the fly to undertake some type of collective art project—to try to turn the abandoned station into a combination underground gallery and group show. They knew they had good connections in both the street art and gallery art worlds. They also knew they had to be careful as they assembled the project's participants, had to tap into "a community of people we were friendly with and we had relationships with," as PAC explains, "partially because we were inviting people to do something which we knew we were going to have to keep very quiet for...a year, maybe two years.... We were going to be complicit in this illegal activity with them...and wanted therefore to either have a pre-established relationship with them or some sort of trust there in the community to make sure they didn't run and rat us out, and we didn't do that to them." Beyond that, the Underbelly Project mostly just emerged out of those relationships, and as PAC says, "happened organically along the way" without much of a plan. "I came from a punk rock background," Workhorse adds, "So I'm kind of used to that kind of thing....a natural extension from that 80s, punk rock, do it yourself...that kind of lifestyle." [i]

[3] Eventually, there would be a scheme for turning the abandoned subway station into this collective art project—for surreptitiously ferrying 100 street artists from around the world down into that station and out again, over a two year period, while dodging detection and arrest and injury—and a rigorous scheme at that. Eventually, that scheme would indeed fill the space with a global array of street art and graffiti, with murals of rats and bears and totems, with stenciled figures and ghostly installations, with poetry and statements of artistic intent, and with a big painted declaration: We Own the Night. Eventually, the Underbelly Project would make the front page of The New York Times, would put in an appearance at Miami's Art Basel, and would be reproduced in the depths of the Paris subway. Over time, the project would come to be commemorated in a glossy Rizzoli art book (Workhorse and PAC, 2012), and in articles like this one. But early on there were just Workhorse and PAC, their do-it-yourself aesthetic, and a distinctly odd sort of undertaking—one that the New York Times article would later argue "defies every norm of the gallery scene" and "goes to extremes to avoid being part of the art world, and even the world in general" (Rees, 2010; see 2010a).

Fig. 6. The Underbelly Project.

Fig. 7. Ian Cox.

Fig. 8. The Underbelly Project.

Fig. 9. The Underbelly Project.

History, Half-hidden

[4] In this sense, the Underbelly Project is, if nothing else, some next stumbling step in the evolution of street art and its relation to the gallery world and the "world in general"—kind of like Australian artist Strafe's stumbling step over and off a subway platform in the middle of the night, in the dark, while painting in the Underbelly. In fact, the trajectory of art culture right up to the Underbelly can itself be seen as a long drunken stumble, replete with thieving, borrowing, occupying, screwing up, and generally mining mistakes and missteps. Looking back from the perspective of the present, from inside art history books and well-mannered museums and galleries, it can seem like it was all straight and honest and clean: new ideas, individual brilliance, a firm march toward beauty or enlightenment or profit. In reality, the whole thing has been more a matter of picking up the scraps, and figuring out ways to make those bits and pieces into something that matters. Dada artist Hannah Hoch recycling the fashion photographs that crowded her little Berlin magazine office in the 1920s into a confrontation with the horrors of World War I, Trinidadians transforming old fifty-five gallon oil drums into Caribbean steel drum music, hip hop pioneers digging through old records, cutting and mixing James Brown yelps and Clyde Stubblefield drum solos to invent a new form of global music and culture—time and again art's forward momentum has run on what was around, with the only question being what to make of it. Then there's Kandinsky, Man Ray, Duchamp, Rauschenberg, Pollock, de Kooning—all artists whose breakthrough works, we now know, emerged out of mistakes and misperceptions, out of cracked printing presses and broken picture tubes (Lovelace, 1996). So as I say, it strikes me that mounting a multi-year, international art project in an abandoned subway station four stories underground, sans legality or audience or fresh air, in violation of the norms of contemporary gallery art and artistic profitability, and with no certain prospects as to what it might become, constitutes just one more gorgeous mistake, one more moment of making do with what's at hand and under foot, one more stumbling step toward...well, toward what?

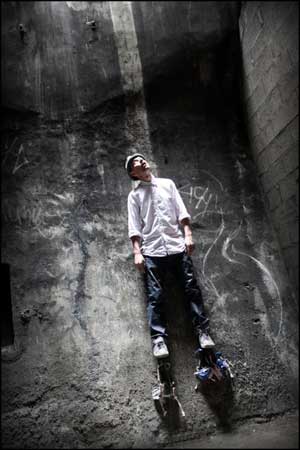

[5] Well, if nothing else, toward engagement with the ongoing trajectory of urban graffiti and urban street art; because from within that trajectory, painting street art in a dank cavern four stories below the street is not as odd as it sounds. After all, street artists and graffiti writers have long played with the dialectics of visibility and invisibility, and have long produced audiences that come and go. As my colleague Robert Weide and I (Ferrell and Weide, 2010) have argued recently, the various "spots" at which graffiti and street art are painted carry distinct meanings precisely because they presume different sorts of audiences and degrees of public visibility. Sometimes, street artists paint primarily for each other, in which case they will often choose secluded urban locations—"yards" or "walls of fame," as such spots are called among graffiti writers—known only to other street artists. Such a strategy both creates a select audience for their work, and promotes its durability by hiding it from unappreciative members of the public or law enforcement. Other times, street artists paint primarily for the general public, or gain status within street art worlds by daring to paint in locations that are highly visible to the public. In such cases, street artists may even go so far as to paint "the heavens"—locations of particularly high public visibility and danger, atop buildings or freeway overpasses. In addition, street artists often select spots based on the happenstance of temporary availability or urban wandering, with an eye toward the existing historical significance of a spot within the cultural geography of the city, or because of a need to promote their work to one new urban audience or another. In each case, the dynamic of street art is never as dualistic as visible or hidden; instead, it is an elaborate game of hide-and-seek played between street artists and their audiences. And in this sense, creating a massive, hidden, street art "wall of fame" four stories underground doesn't diverge from the history of street art and urban graffiti so much as it pushes it one step beyond.

[6] Part of that push comes from the extreme inaccessibility of the Underbelly site, not only for the general public, but also for other artists and street art aficionados, and even for the participating artists themselves, upon completion of their work there. Immediately after revealing the project to a New York Times reporter and a photographer in 2010, PAC and Workhorse undertook to destroy the equipment needed to gain access to the site—thus creating an exhibition that "closed on the same night it opened" (Rees, 2010). Police officers have subsequently stopped and arrested dozens of people as they have attempted to find their way into the site. Australian street artist Lister, one of the participants in the project, argues in this context that, "the main difference between painting in the subpublic, as opposed to the public, is the feeling that you may never see your work again. But this is also the attraction—the idea that someone else, sneaky and adventurous, will receive your work with a different type of intensity than if they saw it where everyone else can. My subpublic works are special gifts for those willing to risk something for nothing" (in Workhorse and PAC, 2012: 118). While this "feeling that you may never see your work again" may be particularly acute in the case of the Underbelly, though, it is by no means unique to it. Explaining the dynamics of graffiti writing, Rasta 68 has argued that "there is no respect in graffiti" (in Ferrell, 1996: 89), by which he means that graffiti writers and street artists cannot reasonably expect their work to survive the "disrespect" of competing artists, legal authorities, and physical deterioration, and so to remain available to be seen again and again. More particularly, as freight train graffiti has emerged as a dominant form of graffiti writing (Ferrell, 1998), graffiti writers increasingly understand that by painting on freight trains they are sending their art away and out into a circulating universe of uncertain images and risky visibility.

Fig. 10. The Underbelly Project.

Fig. 11. The Underbelly Project.

[7] If, in this way, the Underbelly Project has stumbled into, or along with, the half-hidden trajectories of street art and graffiti, there is another level on which it was consciously designed to participate in these trajectories as well, and to reconstitute them. PAC is careful to note that, while the project did in many ways evolve organically out of the connections that he and Workhorse had with other street artists and graffiti artists, over time he and Workhorse also decided to "take a snapshot of what was going on upstairs and bring all of that down as kind of a time capsule. We tried very hard to bring in old school graffiti writers, and really new street artists, and people who were doing strange public installation work, wheat paste work, stuff that involved spray but also stuff that just involved bucket paint, and all those sorts of different mediums that we were seeing upstairs." As a result, the original New York City Underbelly project included the widely known Los Angeles writer Saber (see, for example, Pray, 2005) and old school New York City graffiti king and hip hop designer Haze, who in turn contributed an essay—and a photograph of himself back in the day, as a twelve-year-old graffiti kid—to the subsequent Underbelly book (Haze, 2012: 18-21). By the time the Underbelly Project made its way to the Paris subway the following year, with PAC and Workhorse staging yet another illicit artistic invasion of subterranean space, the time capsule was fuller still. Among those illuminating the darkness deep beneath the City of Lights were Saber, the legendary old school graffiti writer Futura, and an aging but agile Martha Cooper, scrambling down into the Paris underground to photograph graffiti writers and their art, just as she had done, famously, thirty years before (Cooper and Chalfant, 1984).

Fig. 12. The Underbelly Project.

Fig. 13. The Underbelly Project.

Fig. 14. Martha Cooper.

Fig. 15. Martha Cooper.

[8] It's worth emphasizing, though, that the significance of Haze, Saber, Futura, and Cooper—and other participating artists like Revok, Swoon, and Ron English—isn't their star power; after all, as PAC emphasizes, the project wasn't intended "to be something where we were just going to try to reach out to the biggest names we could find. We made a conscious effort not to refer and name drop when people were invited so that they did it out of their own interest in seeing the space and participating." Instead, their participation was meant to reconstitute and recall the historical links between graffiti art, street art, and gallery art, and to situate the Underbelly Project in that history. Put more sharply, many of those involved in the project wanted to restore the appropriate tension, the necessary critical distance, between the street and the gallery; their hope was to remind themselves and others of a world in which street art wasn't aimed only at commercial success. For Workhorse, the idea was not so much to reject the gallery world as to rekindle "the adventure as much as the art," and some of that old punk, do-it-yourself energy as well (in Rees, 2010). Likewise for Haze (2012: 21), the project resurrected the "core essence of it all—the act itself...self expression and identification," and helped restore "the delicate balance between what is personal and what is professional; what is legal and what is not." And notably, Workhorse and PAC chose to conclude the Underbelly book with an essay by Harlan Levey (2012: 235), which concludes that, "the difference between the museum and the tunnels is important....The museum locks down a historical legacy. The tunnel is sure to be condemned. In this sense...Underbelly...offers a quiet stance in the form of a loud statement as it takes the artists back to their roots—isolated, ignored, alone together, enjoying a shared love and a rare burst of silence in the world's loudest city as a time when popularity made that seem no longer possible. Off the radar, Underbelly is a throwback to youth, freedom, discovery, and an orgy of original intentions whose common denominators are action and love."

Fig. 16. The Underbelly Project.

[9] All of which situates the Underbelly Project as a next stumbling step forward and back as well. Graffiti writers and street artists have been writing and rewriting a secret history of the city for a long time now, even when they've been writing it in plain sight. Their role has remained consistently inconsistent, off and on the radar, legal and illegal, caught somewhere between notoriety and acclaim, between the act and the art, moving in and out of the street and the gallery. In fact, it seems to me that good street art always operates in this way, as a coded palimpsest—a palimpsest made not from layers of paint, but from layers of meaning. You see street art and you don't; you figure it out and you never figure it out. It shakes your hand and picks your pocket and then pays you back—sometimes. The more you know about the streets, the community, the traditions, the beefs and the alliances, the more it reveals itself to you; the less you know, the less it has to offer. Because of this street art and graffiti hide in the light, to use Dick Hebdige's lovely phrase—they always know more than they say, always paint their own riddles. "The politics of youth culture is a politics of metaphor; it deals in the currency of signs and is, thus, always ambiguous," Hebdige (1988: 35) wrote. "Subculture forms up in the space between surveillance and the evasion of surveillance, it translates the fact of being under scrutiny into the pleasure of being watched. It is a hiding in the light." Or, as West Coast graffiti writer Crayone said a few years later, "Graffiti writers are the urban shamans and the streets are our modern day caves" (in Walsh, 1996: 64). Or maybe, modern day caves like the one carved out and abandoned by the MTA are our streets, and the shamans are painting in the dark.

[10] In this sense, two further trajectories are, in their divergence, equally appropriate. The first eventually takes the Underbelly Project into the mass media, into the high-gloss world of Miami's Art Basel, into art books and academic journals. The second leaves much of the original Underbelly art tagged over and crossed out by graffiti writers who manage to make their way into the underground space. "Later, some of the art is defaced, not by the authorities, not by MTA workers, but by other artists who found the secret space," says Ron English (in Workhorse and PAC, 2012: 74), "and I'm still unclear as to whether it was an act of rage or revelation."

Performance, Practiced

[11] Workhorse's notion of "the adventure as much as the art," Haze's emphasis on the "core essence of it all—the act itself," Levey's invocation of "action and love," highlight yet another dimensions of the Underbelly Project, and remind us that the project cannot be reduced to its artwork and images, no matter how powerful they may be. The images survive as residues of something more, and more immediate: the collective experience of discovering and occupying that abandoned subway station, and of filling it up with illicit moments of action and love. Even before the project got underway, PAC had spent years sneaking down into the station, just for the pleasure of being there. Though he didn't know about the station yet, Workhorse likewise loved "finding those little pockets of stillness in the city...riding the subway at night....going out at nighttime just walking through the streets...that sense of anonymity and not being noticed." And then to discover the Underbelly space with PAC, "in New York City, the busiest fucking city in the US...to find an area in the midst of all that that's so completely still and dead for communication..." well, for Workhorse that was "a rare find" indeed.

[12] Rarer still was the absence of existing graffiti or wall art in the station—because for as long as there's been graffiti in New York (and other cities), there's been somebody seeking out the next dark tunnel or abandoned building in which to write it. In part, this spatial orientation has emerged out of the necessity of avoiding cops and city clean-up crews; as graffiti writer Eye Six once said, having been pushed to Denver's dark corners by a particularly aggressive anti-graffiti campaign, "all we're basically doing is painting for other writers and puttin' up wallpaper for winos and bums" (in Ferrell, 1996: 104). More so, though, the interplay of graffiti, street art, and marginal urban spaces embodies an experiential aesthetics and politics of the city. West Coast graffiti writer Krypt echoes Eye Six in arguing that "in the tunnels, on rooftops, in abandoned buildings, next to the railroad tracks; that's where we give shit life. We make the gray, the brown, the dirt, into something new, colorful, and ever changing" (in Walsh, 1996: no page number). For graffiti writer and street artist James Cochran, aka Jimmy.C, (2010: 162) such spaces, in turn, define his own art. "The urban experience forms my identity as an artist," he says. "The peripheral and the abject aspects within the city such as the graffiti on the wall or the homeless man in the alley is where, for me, the most meaning is to be found."

[13] In New York City, this orientation has often led to the very sorts of spaces that PAC and Workhorse discovered. Sketching a history of New York City graffiti, Haze emphasizes that subway tunnels were "the playing fields and lifeblood of our sport," and notes that by the mid-1970s, various graffiti crews were already being crowned "kings of the ghost stations." Perhaps most famously, in the 1980s, New York City graffiti writer Freedom discovered an Amtrak tunnel—soon enough dubbed the "Freedom Tunnel" in the graffiti underground—where he began to paint an elaborate series of graffiti murals. Recorded in Chalfant and Prigoff's (1987: 13) book Spraycan Art, documented in Toth's (1993) anthropology of the tunnel's homeless residents, visited countless times by top graffiti writers from around the world (Snyder, 2009: 85-88, 132-135), the Freedom Tunnel exemplifies the marginal spatiality—and situated spatial experience—of graffiti writing. Legendary graffiti writer Lee Quinones admits that "I was always scared shitless down there in the tunnels," but nonetheless embraced the "meditation and discipline" it took to paint in them (in Toth, 1993: 132-133). Even Freedom allows that "I hate the danger, I hate risking my life" to paint in the tunnels, but "I get an idea in my head for a piece and I can't get rid of it, and I have to do it because, if I don't, no one else will" (in Toth, 1993: 123).And when Freedom finally left the tunnel in 1995, he found himself "a little bit dazed," not by the daylight, but by the realization that his artistry couldn't come with him. His art, and his experience of creating it, remained profoundly site-specific (Freedom 2010; see Austin, 2010).

[14] Knowing this history of New York graffiti, knowing how it had over the years seeped into and saturated the city's lost spaces, Workhorse and PAC knew just what an exceptional place they had stumbled into: a big untouched underground ghost station, a subterranean brokedown palace minus the usual artwork of the kings. Knowing this history, they also sensed what to do with it: consecrate it with graffiti and street art appropriate to its degraded grandeur. Acting as the Underbelly's participatory curators, they would round up the best artists they knew—famous, infamous, or otherwise—and accompany them into this monumentally ruined space. And as per this same history, they and their co-conspirators would of course come to animate this space not only with art, but with the intensely situated experience of producing it. For PAC and Workhorse, their countless visits to the station with artists from around the world produced an oddly sequential sort of shared experience, an art community that unfolded one artist at a time. "While we were down there, to be able to stand side by side with someone for a couple of hours and just have a conversation without someone checking their Blackberry or taking a phone call or someone coming into the room and talking to them is such a rare thing to have these days," Workhorse remembers. "To be able to truly get to know someone...and there's just this sort of camaraderie that comes from breaking the law with someone else...and also to do it in New York, the birthplace of graffiti, to take subversive art and return it to its birthplace, was another whole side" to the project. For the artists involved—and especially for those who arrived later in the long-term project, with so much art already accumulated on the walls—the moment was not unlike a graffiti writer's visit to a classic "yard" or "wall of fame": to paint in such a spot was to reconnect with friends and legends, to witness the latest visual innovations, and to know that one's best effort was expected in return (Ferrell, 1996: 49-50, 102-105).

[15] Significantly, this best effort, situated in a space like the Underbelly, does not simply produce art; it is essential to the art itself, and part of it. Some years ago, Stephen Lyng and I came up with the concept of "edgework"—boundary-pushing or boundary-breaking human action that emerges in extreme settings (Lyng, 1990, 2005; Ferrell 1996, 2005; Ferrell, Milovanovic, and Lyng, 2001). Actually, we didn't so much come up with the concept as the concept came to us, while we were participating in the worlds of street motorcycle racing, sky diving, and BASE jumping. In such extreme worlds, we realized, high levels of risk and highly developed skills push participants ever closer to one edge or another; greater skill allows participants to undertake greater risk, which in turn polishes skills and makes possible even greater risk. In dangerous or extreme situations, it is precisely this ability to negotiate the interplay of risk and skill—to let go while still holding on—that defines accomplished edgeworkers. Later, taking this understanding with me into yet another marginal world—the underground graffiti scene in Denver, Colorado, where I spent five years as an active graffiti writer (Ferrell, 1996, 2001)—I realized that successful graffiti writers were likewise masters of skillfully negotiating high-risk situations. And I realized something else: illegality amplified this dynamic of risk and skill. Adding yet another edge to it, demanding the deployment of even more precisely honed skills in the face of serious legal risk, it produced what graffiti writer after graffiti writer described as "the adrenalin rush." "A lot of people paint for the rush, just like sky divers and snow boarders," says West Coast graffiti writer Neon (in Walsh, 1996: 47). And just like sky divers and snow boarders, graffiti writers generate that rush by unleashing their considerable skills within the chaos of the moment—a moment that for street graffiti writers is defined, in addition, by its dangerous illegality.

[16] When Workhorse recalls the Underbelly camaraderie that resulted "from breaking the law with someone else"—and when he another time asks, "Where else do you see a creative person risking themselves legally, financially, physically and creatively?" (in Rees, 2010)—he's describing the Underbelly Project, then, as a distinct sort of artistic community. It's the sort of artistic community that can emerge only in a space defined by its inaccessibility, its danger, and its illegality. Notably, it's not a communal experience animated by some sort of simplistic outlaw machismo—as Ron English says upon spotting some track workers while in the Underbelly, "of course they're probably a lot tougher than us" (in Workhorse and Pac, 2012: 74)—but by an accelerating spiral of illicit artistic possibilities. In that moment and in that space, the interplay of skill, risk, and illegality produces an artistic experience otherwise unavailable—a do-it-yourself "temporary autonomous zone" (Bey, 2003) every bit as definitive as the paintings it leaves behind. Back in my Denver days, local graffiti king Voodoo allowed that, "right before you hit the wall, you get the rush. And right when you hit the wall, you know that you're breaking the law and that gives that extra adrenalin flow (in Ferrell, 1996: 82). Haze agrees. "There is no substitute for the adrenaline and heightening of the senses that kicks in once you enter an illegal zone where you constantly have to watch your back," he says. Endeavoring to clarify the role of graffiti versus street art in the Underbelly Project, he adds that in either case, "a true DIY outlaw spirit" defined the project, and concludes, "As the debate over what is graffiti or not heats up, I prefer to consider it more along these lines: it's not illegal—it's not graffiti" (in Workhorse and PAC, 2012: 20-21). By that definition, of course, all the wall art of the Underbelly is graffiti—or more to the point, all of it is art forged from the same fiery moment of skill, risk, and illegality.

Fig. 17. The Underbelly Project.

[17] Listen to Lister, recalling his time in the Underbelly, and you can hear that moment. The night he went in, he remembers, he was

Worried about falling to my death, getting electrocuted, and most of all being arrested and having to spend at least a night in jail again. But the idea of the secret gallery has always intrigued me, and so I went down....What I wanted to paint came to me instantly. This isn't always the case; there is something unique about waiting to begin with one's imaginings that inspires direction so acutely, especially when a second is all you have to begin preparations.... Instantly I started to shape the form of a face, kind of smirking at first, then smiling.... I started to make the face and then transfer it through my arm and onto the wall; I can only describe it as an action painter's reflection painting, a combination of instinctual balance and mindful precision.... Forty-five minutes later, with drying chunks of paint and wall on my face, I was finished (in Workhorse and PAC, 2012: 118).

Fig. 18. The Underbelly Project.

Fig. 19. Ian Cox.

[18] Likewise, Jeff Soto—who describes himself as a long-retired graffiti writer and "mild-mannered suburban dad [who makes] art for a living"—discovered that once in the Underbelly,

My original idea didn't feel right. I needed to paint something darker, something that represented life and death.... I decided to paint a skull.... I was in the midst of some of world's most notable street artists: Swoon, Ron English, Revok, Dan Witz, Faile.... Now, sneaking around and painting underneath the city felt surprisingly familiar: it brought me back to the excitement and adrenalin I felt as a 14-year-old kid sneaking under fences and hiding in the shadows.... In the dim light it was difficult to see colors and I had to mix nearly blind, relying on my years of painting experience.... There is something undoubtedly primal about painting in the dark (in Workhorse and PAC, 2012: 166).

Fig. 20. The Underbelly Project.

Fig. 21. The Underbelly Project.

Fig. 22. The Underbelly Project.

[19] For SheOne, such moments defined the project in the first place. "I only agreed to participate for the experience," he says. "I paint walls for that exact moment of painting; I am interested in the direct experience of that timeframe and my own output as an abstract artist responding to a unique situation." When the Underbelly later resurrected itself in the Paris underground, SheOne joined How & Nosm and other artists to invent another such moment somewhere below the city and outside its laws. "I always improvise; I like to let the paint and the situation dictate the density of the works.... How & Nosm paint so fast and in such detail, they kind of set the pace, everyone else was just playing catch up.... We noticed afterwards that everyone's gas mask filters had turned pink" (SheOne, nd).

Fig. 23. Ian Cox.

Fig. 24. Martha Cooper.

Fig. 25. Martha Cooper.

[20] As these moments accumulated, then, the Underbelly Project took shape as a collective exercise in transgression—and transgressive art. Great word, transgression: it suggests not only crossing over spatial boundaries, trespassing on spaces owned by others, but violating boundaries of morality and meaning, too. But if that's true, then transgression also means pushing past the limits of law and imagination that were in place when such boundaries were drawn; it means crossing over into some new world while negotiating the limits of the old. And in that sense, I'm not sure there's any such thing as art without transgression—decoration maybe, but not art (Ferrell, 2009). So, as regards the Underbelly and otherwise, forgive us our trespasses...or don't. By making art in transgressive circumstances, you learn to bring your skills to bear under the weight of risk—risk to your body, to your career, and to your legal standing. In my experience, as in that of Haze, Voodoo, and others, this tends to sharpen your game and your senses, to create the sort of incendiary spark you don't often get in a gallery. Better yet, that spark is visceral, a creative passion you feel in your gut as much as you understand in your head. In that sense, artists in such situations are not only "engaging" in transgression, but actually living it—actually translating the violation of rules and boundaries into the pleasure of embodied experience and the distinctive accomplishments of artistic adventure. Not a bad trick—a sort of performance art of the thing itself, with or without an audience in the moment or after the fact, where the artist and the art end up transformed by the performance. Echoing SheOne's notions of painting graffiti for the "direct experience," Sound-One argues that, "the act of doing graffiti, performance art done by and for the artist's personal satisfaction, is graffiti in its truest form. The paint on the wall is purely an after-effect depicting the hard-core struggle to be free" (in Walsh, 1996: 28). With this struggle going on as part of a collective project like Underbelly, a whole transgressive artistic community began to coalesce, at least for a while.

[21] For this to happen, though, the larger Underbelly project had to replicate the dynamics that animated each of its transgressive moments, and that define edgework itself; it had to negotiate on a collective level the same interplay of practiced precision and real-time risk. Or to put it another way: a considerable degree of collective self-discipline is required to engineer a transgression as monumental as the Underbelly. For the Underbelly project, this meant that the absurd, ongoing risks of the project—at a minimum, collective illegality and serial trespass by a hundred or so citizens and deportable non-citizens, down from a busy city and a busy subway platform into a dark, inaccessible, and dangerously isolated place, over a seventy-two week period—had to be cut with a big dose of planning, scheduling, and on-the-ground practicality. In his preface to the Underbelly book, PAC (2012b: 8-10) talks about the history of the project, the underground space, the sense of community—but mostly he talks about "preparation" and the practical rituals that flowed from it. "I remember the counting of headlamps, batteries, light stands, and tripods," he says. "I remember checking to see if batteries were charged and if cans had been shaken.... Mostly I remember lacing up my boots as tightly as possible, a ritual that would come to define my adventure. I remember the rules, a long list of what ifs, dos, don'ts, and in-case-of-emergencies." Both PAC and Workhorse, in turn, intercut the book's prefatory essays not with images of the Underbelly's art, but with images of its practical prerequisites: PAC's worn-out boots and filthy jeans, lanterns, headlamps, and respirators. If, in this way, boots and batteries make up the Underbelly's introduction, it seems only appropriate; without them, there would be no art to follow.

Fig. 26. The Underbelly Project.

Fig. 27. The Underbelly Project.

[22] Then there's the matter of what organizational types like to call "risk management." Certainly, this involved PAC and Workhorse impressing upon participants, in the strongest possible terms, the need for ongoing secrecy. But as PAC's remarks suggest, and as Workhorse emphasizes, confronting risk also meant developing a set of rules and procedures designed to safeguard the project's inherently unsafe moments of illicit creativity, and to ensure that the project would survive to spawn its next transgressive moments. Like PAC, Workhorse remembers that "there was a certain ritual aspect" to it all. "We saw it as being more a military operation, a certain precision that you had to have," he says. "Before we took people down there...we showed them videos of where they were going, what they're doing, the wall that they were going to do, how long they would have, the problems they would have, the way they would enter in. So we gave everyone like a full military briefing before they went in." Echoing the old punk ethos of do-it-yourself and Workhorse's own background in organizing punk events, the Underbelly's autonomy was not merely a matter of independence from gallery sponsorship or grant money; it was also a practical autonomy of self-planning and surreptitious organization.

[23] The artists involved in the project picked up on and appreciated this do-it-yourself attention to detail, and the way the project's details dovetailed with its broader meanings. Noting how quickly the project has become "legend," Swoon talks about the "awesome distance between what goes into making something like this, and what the thing becomes in the minds of people." And as for PAC and Workhorse,

The stuffed-down anticipation, the militant attention to detail that goes into creating something that is simultaneously illegal, extremely long term, participated in by hundreds of people, and yet secret. It's only now, after years of willing things into being with my skin and bones that I recognize the state they were in instantly...and no, I don't envy them one bit. Well maybe a little, because man, what a beautiful thing. What a beautiful, hard-to-pull off thing" (in Workhorse and PAC, 2012: 90).

The subsequent Paris Underbelly Project ran on a similar militancy of detail and coordination—including even an evacuation plan should Saber's asthma overwhelm him amidst the dust and paint fumes. In this context, Futura (2011), himself a veteran of more than a few well-planned graffiti operations over the past decades, offers some words for the video game set. "You know it's one thing to play Modern Warfare 3 Spec Ops: Parisian Metro," he said. "But the precision and logistical coordination was, without question, a highlight in danger and daring." Back in New York, Jeff Stark (in Workhorse and PAC, 2012: 186) sums it up most succinctly, and along the way catches the irony and interplay of illegality, edgework, and mythic transgression. "The heads want to know how these guys pulled off a magic trick," he says, "and I'll tell you as much as I know: rules. If you want to break the law, you have to follow the rules very closely."

Fig. 28. Ian Cox.

Fig. 29. The Underbelly Project.

Meaning, Liquefied

[24] As the Underbelly Project got underway, there was one plan that PAC and Workhorse didn't have in place: a plan as to what the project would become. PAC recalls the initial commitment to filling the space with art, but beyond that mostly "random connections that then propelled the thing forward one more step." Workhorse elaborates:

At the root of it we knew that we wanted to get certain artists in there, we knew wanted to put work on the walls, and of course we wanted to document it because we knew at some point it would be inaccessible. Beyond that, we didn't give a shit about any of it. My job was to put people in a space where they can make art on the walls, and that was it; it wasn't to read about it or try to dissect it or whatever else....At the end of the day, it was just fun. I think it bugs people that there's not a sort of higher calling to it a lot of times, but I think that whatever conversation does happen is better left to other people, because [when] you start to think "why am I doing this?" at the moment, you poison it.

SheOne recalls a similar immediacy. "At the time I went down the project was still balanced on a knife's edge," he says. "It could have been shut down at any moment and remained unrealized forever. When I made my piece I had no idea there was going to be an exhibition or a book; due to the nature of the project I was only aware of a handful of artists involved, so when it all finally came out I was as surprised as a lot of people."

Fig. 30. Ian Cox.

[25] Of course, the project did eventually come out—in part because PAC and Workhorse decided to reveal it to a New York Times reporter and photographer before closing off the space, and in part because of PAC and Workhorse's own meticulous visual documentation of the project and its history. This dialectic between immediacy and image increasingly defines the larger worlds of graffiti and street art as well. The prevalence of photographic and video documentation means that moments of edgework are now regularly resurrected as edgy images, their immediate meanings elongated as they are viewed and evaluated in contexts other than their own (Ferrell, Milovanovic and Lyng, 2001). Within the calculus of the Underbelly Project and other contemporary street art endeavors, the necessary invisibility of the illegal act eventually gives way to the public visibility of its image; the inaccessibility of the physical location morphs into the endless accessibility of digital documentation (Snyder, 2009; Ferrell and Weide, 2010). And yet, as SheOne emphasizes, the pervasiveness of the image doesn't preclude a critical consideration of its time and place within street art and graffiti. Speaking of the Paris Underbelly, he recalls his confidence in the documentary skills of accompanying photographers Ian Cox and Martha Cooper. "After all," he says, "most people experience art through photography these days, either on the internet or through books. I started making graffiti because of Martha's photo journalism, and to have her now photographing me at work twenty five years later was added inspiration" (SheOne, nd; see Cox, 2011). Then again, for SheOne it was equally important that the immediacy of the act, and the sustained secrecy of the project's accomplishment, precede any dissemination of its documentation—important, that is, that the project not initially be befouled by its own image, by pre-publicity, "teaser videos, behind-the-scenes images, live tweets, [and] instagrams."

Fig. 31. The Underbelly Project.

[26] Here is the work of the street artist in the age of digital reproduction (Benjamin, 1968). Here are the street artist and the graffiti writer hiding in the light once again, negotiating the interplay of secrecy and self-promotion, crisscrossing Hebdige's "space between surveillance and the evasion of surveillance." And for the Underbelly Project and its organizers, there exists one more bright shadow in which to hide: the light of the gallery scene. Various commentators have criticized the Underbelly Project for subsequently staging a gallery show at Art Basel in Miami or for producing a high-gloss book, arguing that these developments undermined the project's street legitimacy. Though generally not giving a shit about such criticisms, as Workhorse would say, PAC himself agrees that "ultimately, the choices we've made to put out a book, and even to reveal the station to the press, are all things that, while bringing the project into public light and consumption, and making people aware that these kinds of things are happening, [do] in some ways diminish from the romanticism of the project, that is purely about doing it and never telling anybody." For PAC and Workhorse, though, such endeavors have been less about selling out than about carrying on. As the Underbelly Project evolved, PAC realized that "pursuing it over a longer term and on a global scale is one of my interests." Given this, he says, "part of the reason that the Miami show happened, and that the book happened, is so that we can figure out a way to fund these activities." Workhorse likewise sees an emerging trajectory that takes the Underbelly in and out of the light. "I think it's our goal for the future that each year we do two different Underbellies; one of them is legal, one of them is illegal. The sole point of the legal one is to finance the illegal one. So with Miami, that's essentially why we did that."

[27] These intimations of ongoing subversion suggest something of the Underbelly Project's lasting, if liquid, accomplishment. It's not just that the Underbelly's art has now climbed out of its original catacombs; it's that the meaning of the project escaped understanding from the first, and now continues to escape gallery curators, legal authorities, art critics—to escape even its organizers and admirers. The Underbelly Project is The Great Escape—that old 1960s film based on an incident during World War II, where Allied prisoners of war spend months underground, tunneling out of a Nazi prison camp. The guards and camp administrators are sure they're in control, sure they have everything under surveillance, but in fact, they never know about the tunnel until it's too late and the prisoners have tunneled out. Or is that they never know about the Underbelly Project until it's too late and the art has escaped? This in itself seems a serious, ongoing exercise in conceptual art, and performance art: sustaining a secret art action for so long, right under the feet of those who would have stopped it if they'd known, and now continuing to do so. Making art that's got to be good looking if for no other reason than it's so hard to see, then letting us see it. And like all good art, subverting certainties along the way, sending us all a shudder of realization that we really didn't know what was going on all along, and that we don't now, either. I mean, the Underbelly does make you wonder, doesn't it: what other secret projects are currently being carved out underneath the ground of everyday life?

Fig. 32. The Underbelly Project.

Fig. 33. The Underbelly Project.

[28] PAC hopes for just such subversive uncertainty, hopes that the Underbelly Project will in fact continue to liquefy meaning and undermine assumptions. Echoing Swoon and other participants in the project, he imagines those who have encountered the project now "walking around the city, and every keyhole being an opportunity for some amazing, crazy thing to be happening behind that door." As he says, "This myth has been created, and that really has the ability to transform people's vision of what may be happening in the city, and therefore what will be happening in the city. It changes people's imagination. I think that's really important in cities, too, which can become very stagnant, and your expectations of what sort of behaviors are supposed to be happening are reaffirmed every day....Things like this seed your mind, and that's good for the public." Maybe this ongoing radical uncertainty, built as it is on a foundation of meticulous execution and sustained stealth, situates the Underbelly Project as a monumental, never-ending exercise in collective edgework. Maybe it defines the Underbelly as some long breathless moment, hanging always between execution and discovery. Maybe it means that the Underbelly will continue to confound reviewers, to confuse those unaccustomed to the secret of hiding in the light, leaving them to describe it as "an exhibit that neither spectators nor buyers are able to see...one of the largest exhibits of street art ever shown" (Green, 2010). Who knows? Because after all, if two happenstance organizers and a hundred independent artists can pull off something like the Underbelly, and can continue to pull it off, without grant money or sponsors or permission, then maybe anything is possible. Anything...

[29] New York City (AP, April 1 2120). Archeologists exploring the flooded ruins of New York City reported on Thursday the discovery of a vast subterranean network of illustrated rooms and tunnels. In one of their deepest dives to date, taking them some four stories beneath the surface of the abandoned city's flooded streets, a team of archeologists from the University of Western China (formerly Oxford University) came upon a labyrinth of paintings, murals, and wall writings. Photographs released to the press revealed a series of still-vivid designs—though, unfortunately, many were partly obscured by large schools of deepwater aquatic rats. "The nature of these wall paintings suggests that, in its time, this must have been a place of great mystery and beauty," said team leader Professor Thierry Guetta IV in a press conference back aboard the research ship HMS Mao Zedong. "Either that, or the arts and crafts wing of a prison for the criminally insane."

Notes

[i] All unattributed quotations in the text from PAC, Workhorse, and SheOne are taken from interviews with the author, as listed in the references.

References

Austin, Joe. 2010. "More To See Than a Canvas in a White Cube: For an Art in the Streets." City 14(1-2): 33-47.

Benjamin, Walter. 1968. "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" in Illuminations (Hannah Arendt, ed.). New York: Harcourt, Brace and World: 219-253.

Bey, Hakim. 2003. T.A.Z.: The Temporary Autonomous Zone. New York: Autonomedia.

Chalfant, Henry and James Prigoff. 1987. Spraycan Art. London: Thames and Hudson.

Cochran, James (aka Jimmy.C). 2010. "Aero Soul City." City 14(1-2): 162-163.

Cooper, Martha and Henry Chalfant. 1984. Subway Art. London: Thames and Hudson.

Cox, Ian. 2011. "The Underbelly Project Paris." Wallkandy.net, at «http://wallkandy.wordpress.com/2011/12/31/the-underbelly-project-paris/», visited 20 April 2012.

Ferrell, Jeff. 2009. "Theft, Art, Crime...Revolution?" in Gavin Morrison and Fraser Stables, eds., Lifting: Theft in Art. Aberdeen UK: Atopia, pages 40-44.

Ferrell, Jeff. 2005. "The Only Possible Adventure: Edgework and Anarchy" in Stephen Lyng, ed., Edgework: The Sociology of Risk-Taking. New York: Routledge, pages 75-88.

Ferrell, Jeff. 2001. Tearing Down the Streets: Adventures in Urban Anarchy. New York: Palgrave/MacMillan.

Ferrell, Jeff. 1998. "Freight Train Graffiti: Subculture, Crime, Dislocation." Justice Quarterly 15(4): 587-608.

Ferrell, Jeff. 1996. Crimes of Style: Urban Graffiti and the Politics of Criminality. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Ferrell, Jeff and Robert D. Weide. 2010. "Spot Theory." City 14(1-2): 48-62.

Ferrell, Jeff, Dragan Milovanovic, and Stephen Lyng. 2001. "Edgework, Media Practices, and the Elongation of Meaning." Theoretical Criminology 5(2): 177-202.

Freedom. 2010. Interview at «http://missrosen.wordpress.com/», visited 7 February 2012.

Futura. 2011. Interview at brooklynstreetart.com, posted 28 November 2011, visited 13 February 2012.

Green, Grace. 2010. "The Underbelly Project," The Huffington Post (November 2), visited 6 Feb 2012.

Haze. 2012. "By Any Means Necessary" in Workhorse and PAC, We Own the Night: The Art of the Underbelly Project. New York: Rizzoli: 18-21.

Hebdige, Dick. 1988. Hiding in the Light. London: Routledge.

Levey, Harlan. 2012. "The Art of Rebelling" in Workhorse and PAC, We Own the Night: The Art of the Underbelly Project. New York: Rizzoli: 232-235.

Lovelace, Carey. 1996. "Oh No! Mistakes into Masterpieces." ARTnews 95(1), pages 118-121.

Lyng, Stephen. 1990. "Edgework: A Social Psychological Analysis of Voluntary Risk Taking." American Journal of Sociology 95(4): 851-886.

Lyng, Stephen (ed.). 2005. Edgework: The Sociology of Risk-Taking. New York: Routledge.

PAC. 2012. Telephone interview with author (10 February).

PAC. 2012b. "Like Walking on the Moon" in Workhorse and PAC, We Own the Night: The Art of the Underbelly Project. New York: Rizzoli: 8-10.

Pray, Doug. 2005. Infamy (documentary film). Los Angeles: Paladin.

Rees, Jasper. 2010a. "Street Art Below the Street and Out of Reach." The New York Times (1 November): C1, C5.

Rees, Jasper. 2010b. "The Greatest Show Unearthed" London Times Magazine (31 October).

SheOne. nd. "SheOne on Underbelly–Paris." Interview with Helen Soteriou, Modart, at «http://www.modart.com/2012/01/24/sheone-on-underbelly-paris/», visited 19 March 2012.

SheOne. 2012. Email interview with author (8 April).

Snyder, Gregory. 2009. Graffiti Lives. New York: New York University Press.

Toth, Jennifer. 1993. The Mole People: Life in the Tunnels Beneath New York City. Chciago: Chicago Review Press.

Walsh, Michael. 1996. Graffito. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Workhorse. 2012. Telephone interview with author (8 February).

Workhorse and PAC. 2012. We Own the Night: The Art of the Underbelly Project. New York: Rizzoli.

Fig. 34. The Underbelly Project.