Adventurers

Turned Tale-Tellers:

The Emergence of an On-line Folk Art Community

Anastasia Salter

University of Baltimore

[1] The formative years of computer gaming saw the birth of a genre dedicated to storytelling as a primary experience. These games, adventure games, briefly rose to dominance within the industry in the 1990s but faded fast. Sequels in the major franchises and planned games for the new millennium were mostly cancelled, and the genre is often held up as an example of a failed experiment where games tried too hard to play the role of traditional media. Yet while commercial innovation fell to the wayside, fan communities continued to keep the genre alive, passing around games deemed abandonware and building their own games, both extensions of the familiar and new narratives. These projects emerged from communities united not by love of any single classic game but by devotion to a genre, a form, which the members of the community extended and rebuilt. The fans who created ways to extend this form of gaming throughout two decades were concerned less with evolution in graphics and processor speeds than with keeping games playable and available on modern computers. Their efforts created value even in games that had been left unsold by developers for ten years or more, and revitalization in the genre has begun with innovation moving freely from communal to commercial space.

[2] Adventure games, with their strong focus on narrative and point-and-click exploratory interfaces, ruled the market of the late 80s and 90s with classic series like King's Quest setting sales records and generating new installments as late as 1994 (Business Wire, 1994). But the genre hit a turning point: graphics-based games, and the rise of 3-D, made the cartoony two-dimensional environments of the adventure games suddenly look dated. Attempts to bring the games into the new style failed, with later releases attempting to embrace action and in doing so alienating the franchises' followers. While the series, and the adventure game genre, were near the peak of their success, Espen Aarseth argued for the expanded study of adventure games, a genre of computer game devoted to narrative experience, not as a bastardization of a literary form but as a literary form in itself: "The adventure game is an artistic genre of its own, a unique aesthetic field of possibilities, which must be judged on its own terms" (1997, p. 107). He noted the roots of the genre as, perhaps, more in folk art than in commercial art: the story of the 'first' adventure game "is a paradigm of collaborative authorship on the Net: one person gets an idea, writes a program, releases it (with the source code); somewhere else another person picks it up, improves it, adds new ideas, and rereleases it" (p. 99). This allows for the classification of this first adventure game, at least, as "folk art" created through a repurposing and expanding by authors building a narrative tradition (p. 100).

[3] Even as the adventure game is being continually redefined and repurposed by the commercial arena, there are still authors continuing the genre outside of the commercial realm. These authors work in a manner that is collaborative and yet personal in the tradition of Adventure itself: they build games and tools, share those processes and their code, and expand upon the games and tools made both within the community and outside in commercial projects. These authors are not merely continuing the tradition of the "original" games but, more importantly, are adding their own ideas. The works of this tradition are a glimpse at the future of electronic literature. These are games created not by so-called independent or corporate collectives, but by individuals working within a collective to evolve this style of interactive narrative in their own images. They are no longer simply observers of games: "What happens when producer and consumer merge in a single interactive medium as prosumers, who can readily create as well as consume..." (Bronner 24). Many of these "prosumers" would not identify themselves as aspiring to the revolution of literature, yet their patterns of practice resemble the days of literary salons made virtual—and, indeed, resemble the practices of the original adventure game creators. It is in the growing communities that celebrate this form of authorship that we can see a narrative tradition growing from early examples, not unlike the stories originally serialized at the birth of the novel. It is here—and in spaces like it, throughout the Internet, where older forms of popular culture are routinely processed, consumed, re-mandated, and taken as inspiration for new content that holds its audience through a shared heritage of stories built toward a world of new ideas.

[4] The fandom surrounding classic adventure games fits Matt Hills' description of a fan culture: "A fan culture is formed around any given text when this text has functioned as a [part] in the biography of a number of individuals; individuals who remain attached to this text by virtue of the fact that it continues to exist as an element of their cultural experience" (108). As Jenkins notes, these communities defy the limits of physical connections: "Online fan communities might well be some of the most fully realized versions of Levy's cosmopedia, expansive self-organizing groups focused around the collective production, debate, and circulation of meanings, interpretations, and fantasies in response to various artifacts of contemporary popular culture. Fan communities have long defined their memberships through affinities rather than localities" (137).

[5] Members of one such creative group, the Adventure Game Studio community, are often, if certainly not always, of an age to have grown up with classic era (1984-1995, approximately) adventure games. They are likely equally able to recall formative experiences with their first adventure games. The AGS community is now twenty-years old and had already formed when games like Myst were bringing adventure games to a wider audience and starting to shape the demographics of casual games. Such demographics don't much resemble the stereotypes of teenage males as the only serious gamers. AGS itself is founded on free creation and free content. In this, the community is part of a larger trend online: what David Bollier terms the "viral spiral." Bollier is describing the seemingly chaotic process of social creation centered on programs just like AGS: "The viral spiral began with free software (code that is free to use, not code at no cost) and later produced the Web. Once these open platforms had sufficiently matured, tech wizards realized that software's greatest promise is not as a stand-alone tool on PCs, but as a social platform for Web-based sharing and collaboration" (Bollier, 2008, p. 3) AGS is only one of the many options for free or paid-for creation tools: however, of such tools, it is the only one at the center of a strong sustained community. Other tools tend to be more narrow or inaccessible, driving off communal participation. This allows AGS to play a significant role in David Bollier's posited viral spiral. The freely created content, both in the forms of tools and narratives, inspires further creation and cycles through the community. Works produced using AGS tools occasionally appear alongside commercial releases on reviewing sites dedicated to the remaining outputs within the genre. Players are more willing to pick up games reviewed in this manner because of the nonexistent price tag, and would-be creators are not barred from the process by the expense of tools. The greater influence of the adventure game fans would not have been possible without the communal aspect.

[6] I first came to observe AGS as a community through their role as archivists and gatekeepers to the not-all-forgotten adventure games of the classic era. Remakes of several classics are made using the AGS tools, and while the community itself is against illegal abandonware and blocks links to such content, a communal respect for classic works keeps them alive. The members of this community are a subculture of fandom with a specific textual heritage. However, the genre of their allegiance is adventure games. The shape of this fandom is different than one built around, say, Monkey Island itself, the community is not drawn together by any one game or series but by the form.

[7] Putting the Adventure Game Studio into the larger context of fan productions requires first recognizing what makes the AGS community unique. Over my two years observing the community, I noticed two trends:

- The Adventure Game Studio fan movement has sustained itself for a decade developing narrative games in parallel to and in conversation with the mainstream gaming industry.

- A larger recognition of remix culture has applied various labels to this type of movement, but this particular fandom has gone largely ignored—in part, perhaps, because while other fandoms focus on clearly identifiable media artifacts this fandom focuses on a narrative style.

[8] The AGS fandom and similar communities have sustained themselves for decades while going largely unnoticed, creating games in parallel to the mainstream. At first, such production often seems to be in one-sided conversation with corporate creation. However, over those same decades fan production has come under closer study, and we've come to appreciate that this practice does not occur in a vacuum. The remix culture, as named by Lawrence Lessig, has power, it influences motion of ideas within and beyond a community: "Remixes happen within a community of remixers. In the digital age, that community can be spread around the world. They are showing one another how they can create...that showing is valuable, even when the stuff produced is not" (Lessig, 2008, p. 77). Members of the community play both commercial games and fan games, and while it appears that only other fans play fan-created games, the current trends in production suggest there is a back and forth. Given that: what is the power of Adventure Game Studio? Does it impact the larger world of games?

[9] To understand the scope of the movement, I will look at classic games and their players as contrasted with fan games and their creators. Players have never been passive: though it is tempting to talk about games as narratives in a traditional sense, and these games are even more story-central than most, it is important to keep the role of player distinct from that of reader. As Jesper Juul points out: "The relations between reader/story and player/game are completely different - the player inhabits a twilight zone where he/she is both an empirical subject outside the game and undertakes a role inside the game" (Juul, Games Telling Stories, 2001). Juul wrote to discourage the literal projection of film and literary models onto games—a position that emphasizes that active role of the player and the variance among play experiences. The type of authorship that the early adventure games required from players was more metaphorical than literal: the players did not write any of the text, and while their emotional investment was required for the power of the narrative, it was not required for its execution. Yet the current transformation is from player to author. Creators today are emerging from the first generation to grow up with video games embedded in their early experience, and this state—the state of the digital native—allows for a different approach to the process of creation. Previous game creators were shaping the form from the influences of traditional narratives—the games they created were necessarily compared with literature and film because these were the models available for both inspiration and contemporary parallels.

[10] The blurring of the positions of reader and author is happening everywhere on the web. Posters on YouTube remix, imitate, and innovate in short video postings that can respond to one another in linked webs of dialogue. Writers and artists create fanfiction and fanart that keeps a series long "dead" in the hands of its producers alive—witness the large communities around Harry Potter, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and even the original series of Star Trek. Players of massive multiplayer games become co-creators of the game experience, building their characters and creating the social networks and add-ons that make the game a lasting world. The world of Little Big Planet expands endlessly beyond its initial platform content with the constant addition of new user-created levels that other users in turn play and respond to. It is tempting to see the adventure game creators as just one more node in this growing culture of co-creation.

[11] Some of the first documented communities of fandom surround the various elements of the Star Trek universe. Coppa takes a look at the practice of making videos, or "vidding," within those communities. This practice is, as a technological exercise, a matter of taking clips from episodes and restructuring them with new music to create a different atmosphere. Coppa argues that the motive for the practice is repossessing these characters and literally placing them within a desired context that is more empowering for the fan creator: a similar practice to taking an old game and bringing forth a desired relationship or event, or even rewriting an unwanted ending (Coppa, 2008). The work of AGS community members, on the other hand, only occasionally works with artifacts from the original commercial games—more often, AGS members remember the original, but are concerned with shaping the new.

[12] Yet there are a few aspects that make this community a microcosm for considering the future of co-creative work. As the community has existed for ten years, continually unified by one main forum and software tool, it is easily defined in its age and scale. While few records have been maintained as to the exact nature of the community throughout the years, the evolution of the creator has tracked the general demographics. All the produced content is made freely available online, and the community encourages and hosts these works, allowing a better grasp of the range of content. Obviously some projects remain private and impossible to track, while others are begun and reach certain stages without ever being published in completion, but a large archive does exist covering most of the work. Very few forms of co-creative content exist in this type of cluster, particularly in relative isolation. While other software tools exist for creating adventure games none has built this type of presence. The community remains in a state of production throughout all seasons, with new members coming and going and projects posted regularly throughout the year. Some are elaborate games, some single-room affairs without much content, but nearly all are made freely available and commented upon by others.

[13] The forums are continually active: this is not a dead community despite the fact that many of the games that inspired its existence are now unplayable on modern systems. Fans are continually fighting the forces of obsolescence, returning games to a playable state through a number of methods I will be examining throughout. The "viral spiral" continues as fan games are played by and inspire fans, which in turn leads to evolution within the creation tools themselves. The conversation is ongoing.

[14] Despite this apparently harmonious model, some suspicion of an open-source, creative-commons world even exists within the community itself: the creator of Adventure Game Studio, Chris Jones, refuses to release the source code. He cites his fears that to do so would not only allow others to turn his code towards personal commercial ends but also allow other people to more easily reverse-engineer others' games (AGS FAQ). This decision has in some ways limited the potential of the software, but the ease of adding modular content and creating "expansion packs" for the original toolset allows innovation to continue. The release of the source code would allow for the program to move a step further, but thus far the same people have maintained the software and continued to release new versions of AGS.

[15] The revolution in content creation that has accompanied the move to digital distribution begins with the model of free creation. The games under analysis here were heirs to commercial products but are not themselves inherently commercial; in fact, most are released with no more expectation than to reach a limited player base that mostly consists of other game creators of the same genre. This non-commercial form puts narrative and expression ahead of technological advancement, as creating a game of modern style requires substantial capital and a large team of varying expertise. The new creators of interactive narrative content in this tradition are not faced with the same challenges as the producers of the classic games. The communities themselves have built and freely shared tools—such as Adventure Game Studio, SLUDGE, and AGI Studio—that transform the process of creation into something manageable by an individual

[16] The Adventure Game Studio community noted that as of March 2004: "The actual average age on the forums at present is 22 years old. There is, of course, a reason for the majority age group being young adults - people that are aged about 20 now would have played games like Monkey Island and King's Quest when they were children, and are now old enough to want to recreate the games" (AGS, 2009). This self description acknowledges the impact the classic games have made and continue to make on the AGS productions, which are themselves created with an interface designed to allow work expanding upon the tradition. The games of the classical era of the genre are continually evoked, both by personal games produced today and by rereleases, re-masterings, and extensions of the classic universes. The patterns of production in these two genres show the transference of creative control from the original corporate authors to fans. The heritage of adventure games both in particular titles and in the general form has become a playground for new content creation. Game making as a cultural production does not belong to corporations and the center of innovation is quickly moving to these outer circles.

[17] Examining personal interactive narrative projects outside of the corporate frameworks still shows a reliance on a folk art tradition. A study of one segment of output, the games produced using the free Adventure Game Studio over the course of six months, reveals the different facets of these creations. Particularly interesting is the creation of an internal heritage network: a series of games, based on an original collaborative creation, that continue to build on a canon produced within the community. These projects, even when created by an individual, reveal a shared world of a different sort where the fan-creations in turn spawn creation, where the individual productions take the place of corporate productions at the center of a network. Most importantly, the games I will be examining draw attention to the potential of this form to bring with it innovations in areas that the commercial world is less likely to hold of value.

Digital Folk Art

[18] Like modders, fanfiction writers, or the creators of fan vids, the new co-creaters of these "neoclassic" adventure games are participants in a fusion of play and labour. They produce content without reimbursement for their time or efforts. That content is in turn made freely available, easily downloadable by fellow enthusiasts through communal hubs like that of the Adventure Game Studio website. The boundaries of the community can be drawn around this space, with its shared communication tools:"Folk groups are readily identifiable on the Internet, as evidenced by chat forums, blogs, online political activity, fan web pages, and a plethora of other interrelated concepts" (Blank 9). Sometimes these releases are even in clear competition with the commercial endeavors of the primary creators, as with the King's Quest remakes and Sierra's re-release of the series. However, this competition goes mostly ignored—the remakes belong to one world while the re-releases occupy another. This is best understood as a symptom of Lessig's notion of the hybrid economy, where distinctions are maintained between an economy of "sharing" and an ecomony of "commerce" (Lessig, 2008, p. 177). The remakes build the value of the games, keeping them alive and active, even if the audience is small. The commercial economy, on the other hand, is more concerned with ownership: while authorship may have passed to the fans, ownership remains in the hands of the creators. Were the fan creators to try and profit from their remakes, they would no longer be in the spirit of sharing and would present a clearer threat to the commercial value of the brand: as it is, their efforts actually add to the commercial. Yet despite the lack of monetary rewards fan co-creators persist and through their authorship continually re-create the worlds of their devotions through a practice of a still-evolving tradition of folk art gone digital. The tools of the trade, with their baseline interfaces and engines providing for the same style of interactions as the early games of the classic era, encourage both adherence to the standards of the genre as well as deviation and further expression through personal consideration of the potential points of departure of the adventure game experiences. Whether that authorship results in new personal games following original storylines or in so-termed "fan games" emerging directly out of works of the classic era, these authors are participating in a post-commercial venue of production that encourages the pro-active remix of cultural artifacts as part of the building of digital folk art. The term folk art is perhaps most appropriate because the producers strive within a tradition, not in the direct wake of a particular work—a path that might mean many of the works appear similar, yet "...textual and visual reproduction on the Internet does not necessarily homogenize cultural expression" (Bronner 35). There is diversity in emergent game structures, even within the adventure game tradition.

Exemplars of the Form

[19] While there are no editorial forces directly at work in the production of personal games, there are editorial venues and systems of merit-recognition that allow some games to reach a wider audience. Certain projects are more talked about within the adventure game community—games that received accolades or response on multiple websites or that were given various awards. Some projects are granted recognition because they are reflective of the community: a recently released personal game, Adventure: An Inside Job, is built as a swan song for the classic era, and thus holds a strong appeal for other player creators. The premise of the game is that all the characters from unreleased adventure games—games that were abandoned or had their funding cut—are gathered in a world built out of classic sprites and screen shots. The game's creator, Akril, noted that "In some ways, ATIJ can be considered a fangame, which would make it one the few fangames that includes ripped graphics and music yet isn't a sequel, a remake or a spinoff" (Akril15, 2008).

[20] This strange status—a derivative game that is not a spinoff—allows the game to exist as a critique of corporate production. Through its very premise it draws its material from truly abandoned games, the type of games where most of the content exists only within the inaccessible confines of the corporate vault. The game is not only a tribute but a satire, a reminder of the potential lost with each abandoned idea that is allowed to languish, incomplete.

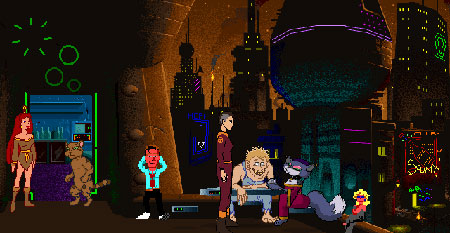

Figure 1: Screenshot from Adventure: An Inside Job displaying the range of "forgotten" characters (Akril15, 2008)

[21] Akril's intention was "to appeal to people who not only love adventure games, but have played too freaking many adventure games" (Akril15, 2008). Akril's wording is interesting: she suggests that appreciation of a game like this, with its critique on the death of the genre, is only possible for those who have passed a certain threshold where they have been immersed in the adventure game canon. The game would be difficult to parse for a newcomer to the genre, as much of the humor and gameplay depends upon recognizing the intertextuality of the content. Yet the implications go beyond mere familiarity—the number of references on screen at one time in Akril's world rival those of a Family Guy episode and encourage the player to probe the depths of their own memory to be "in" on the joke. This buildup of interactions shows a direct response to reading through the shaping of a community. Such developments are a defining aspect of fandom—"the idea that fandom constituted an interpretive community or, more accurately, communities. Interpretive communities are social groups which share similar intellectual resources and patterns of making meaning...There is, of course, never total agreement, but there appears to be some agreement about what kinds of disagreements can be tolerated and which ones throw you beyond the parameters of a particular group" (Jenkins, 2006).

[22] Intertextual explorations are common to the narratives of personal games. Out of Order, released by Hungry Software in 2000, uses a system called SLUDGE—a toolset that the creator designed entirely to meet the needs of his game. Out of Order's main character, Hurford Schlitzing, "stuck in this strange environment with only his pajamas and teddy-bear slippers," recalls Douglas Adams' Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, a novel once reworked into a piece of interactive fiction (LaVigne, 2004). The artistic style of the game is not particularly evolved from the traditional style of the genre. The cartoon graphics, as shown, are at a slightly higher resolution than the early games. The line work adds to the whimsical atmosphere throughout Hurford's journey, which is both surreal and ordinary at the same time—there are echoes of familiar cartoon worlds.

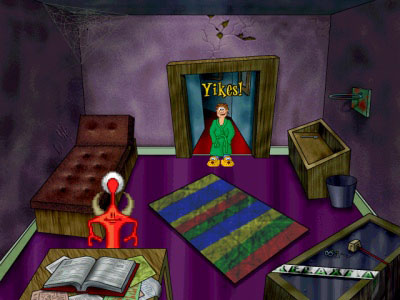

Figure 2: Out of Order

[23] Certain intertextual references, such as the stranding of Hurford in space in his pajamas and the occasional turn of phrase, are impossible to deny. Such connections add to the enjoyment of other fans in spotting the connection to the classics. This again evokes the form most recently popularized by Family Guy. Viewers of the postmodern cartoon Family Guy are presented with a process of symbolic encoding that is heavily reliant on the texts of the seventies and eighties among other sources. Interpreting the episodes fully requires knowledge well beyond the closed text of a single episode or even of the series as a whole. To merely quantify Family Guy's influences, such as The Simpsons and various family sitcoms, does not begin to reveal the symbols at work in the text. The process of decoding can be attempted without awareness of the works being referenced, but such an interpretation is incomplete: in the semiotic model of interpretation, knowledge of the cultural encyclopedia and related texts is essential to decoding meaning. This destroys the notion of the writer creating something new: instead the writer's only power is in a textual collage, in the ability to create "a multidimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash" (Barthes, 1977, p. 146).

[24] Intertextuality is at its most basic the notion of the path which connects meaning to previous texts. These connections do not need to be the conscious intention of the author; indeed, in the world of literary criticism, such connections are drawn while paying little attention to the author's intent. However, in Family Guy these references are conscious and part of the defining character of the show—this is the hyper-commercial transformation that intertextuality has taken. References in Family Guy are thus a case of intentional intertexuality: the show's writers are, as Barthes puts it, orchestrators of the "already-written." The reader is required to participate in this self-conscious form of intertextuality: in the hyper-commercial realm, being "in" on the joke creates part of the essential pleasure of viewing. Similarly, the intertextuality of Out of Order is intentional, and implies its own audience that is willfully held separate from a traditional commercial audience: an understanding of science fiction, a presence as part of the fan game community, and a relationship with more traditional literary texts all allow a player to gain more from the game—the text knows its own reader.

[25] Even more grounded in referential narrative is a 2004 game entitled Cirque de Zale, a game created by Rebecca Clements, who is also notable as one of the few known female creators working within the realm of personal games. Cirque de Zale's graphics are closer to the classic games of early Lucas Arts with a low resolution and simple color palette. The game, shown here, centers on a boy sent through a portal to a fantasy world, where that kingdom supposes him to be the answer to all of their prayers. The expectations set by the genre are very clear: in the main games being parodied, namely the King's Quest and Quest for Glory series, the boy would promptly assume his destined role as hero.

Figure 3: Cirque de Zale's Monkey Island style interface

[26] Instead, Zale dedicates himself to starting a circus, noting that rescuing the princess sounds dangerous and generally like a bad idea. When at one point he is kidnapped by the same person who captured the princess because of the expectation that he'd fulfill the role, he walks right past the trapped princess and leaves her to her fate: he doesn't have the key and he can't free her even if he wanted to. The player can try any approach possible, but the game will not let the player rescue the princess. She's left to rot in the cell, contrary to the classic era assumptions about the role and place of a hero. The designer described her intention to evoke the tradition of Lucas Arts adventures: "I wanted people to get a real sense of nostalgia as they played it, which is exactly the kind of game I'd love to play" (Manos, 2004).

[27] The creator's statement here is ironic: Cirque de Zale is nothing like the old games, and Zale's antics little resemble that of the traditional game heroes who always accepted their quests. The game is a rejection of the commercial formula even as it claims to be a homage—it is evoking a sense of nostalgia, perhaps, but that nostalgia is colored with a realization that the audience has grown and their expectations have changed. The story is like a postmodern folktale retelling that rejects the paths and values of the original tale even as it pays homage to it by viewing the original as worthy of such reinterpretation.

[28] Another Adventure Game Studio release, A Tale of Two Kingdoms, shows more concern with graphics and convincing atmosphere—the same elements more common to commercial innovation. A Tale of Two Kingdoms is the creation of a Dutch team of experienced designers. The game includes wandering non-player characters and allows for multiple endings, an element that remains challenging for any game to incorporate convincingly. Part of the convincing atmosphere is in creating a world for nonlinear play: this is particularly difficult when presenting a fairy tale world, which is familiar territory for most gamers. Part of the atmosphere of the game is provided by the imagining of non-player characters as people going about their everyday lives, a feature that one reviewer commented upon as unusual in this type of game: "I was particularly charmed by the town, where you see many game characters and "extras" strolling around, going about their business as you might expect in a real town. This is a marked contrast to so many games that are full of abandoned villages, characters who just hang around in one spot waiting for you to come and talk to them, and huge metropolises that never actually seem to have anyone in them" (MacCormack, 2007).

Figure 4: Tale of Two Kingdoms

[29] The games to which the reviewer is referring could easily be games typical of the classic era, of the personal games community, or even of modern commercial games—the stationary character is a model established by the limitations of classic systems that has now become a familiar pattern. The game has the feeling of what Sierra might produce today had they not abandoned the genre: it is not a fan game in the way that a direct King's Quest sequel might be classified, but it is highly informed by those classics in design and play. Such a game appears to be the truest form of homage, bearing much more resemblance to the canon than Cirque de Zale, but even it demands a trajectory of innovation. The creators are not merely reproducing that which commercial creation once built—they are expanding upon it and in the process even redefining the very mold.

[30] Perhaps the most innovative individual game in recent years is an experimental game entitled What Linus Bruckman Sees When His Eyes Are Closed, Vince Twelve's adventure game designed around two stories occurring at once. The designer explains the concept: "If someone could read my mental design document they would have read about two worlds, completely unconnected except by gameplay, as different as possible in mood, art, sound, and writing. One, a sad film evocative of a Kurosawa classic except rooted in Japanese mythology, the other an upbeat Saturday morning cartoon about an alien working at an interstellar burger joint. The player would play the two games simultaneously" (Twelve, 2006). Gameplay in Linus Bruckman is true to this vision of connected narratives. The difference in styles between the two linked games is staggering: the highly cartoon imagery of the one contrasts with the surreal mysticism of the other. The AGS community gave Linus Bruckman their award for innovation, acknowledging the move towards a direction very different from the classic era games.

[31] A game like Linus Bruckman is no longer concerned about a dialogue with commercial works: it is pushing the limits of the form as art. Such a game would be as comfortable in the discussions of critics of electronic literature as it is in the AGS community: it might even be there that it finds its aesthetic compatriots. I return to Lessig's thoughts on communities of remixers whose: "showing is valuable, even when the stuff produced is not" (Lessig, 2008, p. 77). Linus Bruckman is valuable, both in its showing and in its innovations. It transcends the expectations of the amateur creator and of the limitations of this type of free tool, reminding its audience that traditional production has its own set of limits that a creator in this medium can defy. This does not resemble any game of the classic era of adventure games—it redefines the linearity and progression of the form in a way that fragments and unifies its player's attention.

Figure 5: The dual screen narratives of Linus Bruckman (Vince Twelve, 2006)

Design Trends in Personal Games

[32] During the period between January 2008 and June 2008, thirty-eight freely downloadable games, as detailed in the appendix, were announced as completed on the AGS completed games forums. This list is representative only of those games where the creator chose to make an announcement, and therefore does not include games produced outside of the AGS toolset or announced within different venues. However, the completed games forum is a popular tool for gaining an audience. Every game post within the forum is responded to, often with pointers about bugs, commentary, and even offers for translation. Thus, the forum is both an ideal tool for announcing the release of a game and for tracking the progression within the community. The information in the appendix reflects the details of these thirty-eight games as indicated by their postings and downloadable versions, and what follows is an analysis of the narrative trends in personal games based upon this sampling.

[33] Of the thirty-eight, only nine can be clearly termed fan games, or games that are clearly derivative of other narrative works and in fact define themselves by that textual link. The first, Maniac Mansion Episode 40 by Rayman, is part of an extended series of short games that keep the characters from the original Lucas Arts game participating in various further mysteries. This game is not particularly inventive in story, as the puzzle is finding the key to allow two of the characters to escape the cellar, but it reflects the original series in style and in humor. The second, AgentBauer's Space Quest IV.5, accomplishes a familiar task of fan games by filling in the missing interlude between Space Quest IV and its official sequel. The Indiana Jones franchise, which was explored in adventure games during the classic era by LucasArts, is taken as a starting point by Rob Shattock in Indiana Jones - Coming of Age. The narrative chosen for extension is not from the adventure games; instead the story takes its cue from the films.

[34] The other examples of fan games are examples of narratives that rework characters and settings, both classic and modern. Ghost's Once Upon a Crime is not a traditional fan game, but it does, like the pop culture phenomenon Shrek, among others, make use of familiar fairytale archetypes re-interpreted. Similarly, Elen Heart's Once Upon a Time is a more traditional fairy tale world retelling presenting mostly well-known characters and settings. Marion's James in Neverland offers beautiful environments to present a Neverland inspired not by Disney's Peter Pan but more so by the original novel. Another fan game from the same creator, Dread Mac Farlane 2, is an adaptation of a French comic book by the same name—it is also the sequel to a game also created by Marion. Both games also incorporate original elements, but the primary focus of Marion's work is in reinterpreting narratives. The remaining fan games show closer adherence to the narratives of their source material: Ultra Magnus' work reaches to the medium of television not only for inspiration but also for graphics and to some extent narrative. His game, The New Kids, takes the Icelandic television show "Lazytown" and uses it as a framework. Games like this are a sign of the international scale of the AGS community: even though it is small in numbers, it draws from a global influence. Skerrigan's Doctor Who - Episode 0 draws upon the familiar world of the television and radio program for a two room game, the narrative of which could translate easily into the Doctor Who canon.

Reality-On-The-Norm

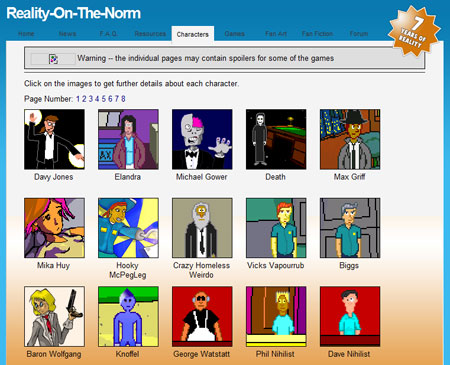

Figure 6: Reality-On-The-Norm character gallery (2010)

[35] Among the remaining original titles, some are related to one another but not to any external text. These games are referred to as RON games, or the Reality-On-The-Norm games. Members of the Reality on the Norm project describe the collective as involving "the creation of a central environment - in our case, the Reality-on-the-Norm town. Each member of the team creates his or her own game as a chapter to be added to all the previously achieved ones, thus creating a collective and diverse "book" of several independent yet coherent chapters" (Reality-On-The-Norm, 2008). Participating in the RON games requires acceptance from the community, which mandates certain rules. For instance, authors are not allowed to kill any of characters within the town, nor are they allowed to claim the work of others as their own. The collective provides backgrounds and characters as well as a persistent narrative that is continually expanding. Two RON games were released during six months: Brentimous's Rock-A True Story, and Bitby's Reality on the Norm game, Au Naturel, one of the few games clearly identified as for a mature audience.

[36] The RON community even acts as the center of its own creations. The page features fanfiction and fanart, some of which juxtaposes the RON characters with icons from classic adventure games:

Figure 7: Fan art featuring RON's Dave and Monkey Island's Guybrush Threepwood

[37] The central hubs of the RON community include work by the "original" creators of the concept and fans who have joined the efforts later side by side. The shared universe resembles commercial worlds, like Marvel or DC's comic universes or Wizards of the Coast's Dragonlance and Forgotten Realms, but those series put barriers on their expansion. Not just anyone can create a new extension to the universe: their efforts have to be approved by the intellectual property holders, and only authorized projects add to the canon of the commercial universe. RON demonstrates how such a universe can exist and thrive outside of ownership when expansion is open to all who desire.

[38] The remaining games of the six observed months reveal a range of narratives, graphics, genres, and even languages—games were released in original languages including French, Italian, and German. This again shows the global reach of the community and the cooperation across languages that allows for frequent translations of fan games for other audiences. Among these, a few stand out for offering original elements, particularly in terms of artistry. Creamy's Bob Escapes offers art that it unusual within the digital medium, as the settings appear to have been drawn by hand using colored pencils, while Eugene's The Oracle heads the opposite direction with backgrounds taken from photos shot on location. Nanobots, a collaboration between The Ivy and Vince Twelve, is a game of particularly high quality created by two who might be considered among the stars of the AGS community. Vince Twelve is also responsible for What Linus Bruckman Sees When His Eyes Are Closed. The narrative of Nanobots pits tiny self-aware robots against an evil professor and thus plays with perspective and philosophies of artificial intelligence. Ivan Dixon's Syndey Treads the Catwalks, which focuses on the life of a homeless man thrust into the spotlight, is clearly the work of an illustrator, as a trip to his website confirms. However, his work is further complicated by a complex relationship with his own transmedia presence—the game is an adaptation of a comic that he created. These games show the constant focus on innovation of all kinds, a reminder that this is not a stagnant place of nostalgia but a community where new canon-worthy works might form entirely outside the purview of commercial media.

[39] While the audiences for the games released varies greatly—some are admitted by their creators to be intended originally for their own family or friends, while others aspire to draw in fans of particular genres or of other narratives—none goes entirely ignored on the AGS forum. The proportion of fan games to original creations suggests a larger interest in original narrative, even if those narratives themselves often acknowledge their debt to other sources. The imagery of these games laid out side by side also reveals the variation of approaches, as the lack of editorial control means that games of any genre, style, or quality can be brought to the attention of the community. However, the community itself acts as a censor, and games that are bug-ridden or show insufficient craft are quickly forgotten. Games that attract an audience continually rise to the top of the forums and are kept alive in the archives of the community game list to form, perhaps, the classics of the personal games genre itself.

Works Cited

Aarseth, E. (1997). Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

AGS. (n.d.). Adventure Game Studio FAQ. Retrieved Nov 17, 2008, from «http://www.adventuregamestudio.co.uk/»

AGS. (2009, January 7). AGS Forum Statistics. Retrieved January 7, 2009, from Adventure Game Studio: «http://www.bigbluecup.com/yabb/»

Akril15. (2008, October 28). Adventure: The Inside Job. Retrieved January 2, 2009, from Adventure Game Studio Forum: «http://www.bigbluecup.com/yabb/index.php?topic=35962.0»

Barthes, R. (1977). Image-Music-Text. London: Fontana.

Blank, T. (2009). Toward a Conceptual Framework for the Study of Folklore and the Internet. In T. Blank, Folklore and the Internet: Vernacular Expression in a Digital World. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press.

Bollier, D. (2008). Viral Spiral: How the Commoners Built a Digital Republic of Their Own. New York: New Press.

Bronner, S. (2009). Digitizing and Virtualizing Folklore. In T. Blank, Folklore and the Internet: Vernacular Expression in a Digital World. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press.

Business Wire. (1994, November 22). Sierra releases King's Quest VII. Business Wire .

Coppa, F. (2008, September 15). Women, 'Star Trek,' and the early development of fannish vidding. Retrieved September 15, 2008, « http://journal.transformativeworks.org»

Hills, M. (2002). Fan Cultures. London: Routledge.

Jenkins, H. (2006). Fans, Bloggers, and Gamers: Media Consumers in a Digital Age. New York: New York University Press.

Juul, J. (2010). A Casual Revolution: Reinventing Video Games and their Players. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Juul, J. (2001, July). Games Telling Stories? Retrieved November 15, 2009, from Game Studies 1.1: http://www.gamestudies.org

LaVigne, C. (2004, March 10). Out of Order. Retrieved December 4, 2008, from Pop Matters: «http://popmatters.com/multimedia/reviews/o/out-of-order.shtml»

Lessig, L. (2008). Remix: Making Art and Commerce Thrive in the Hybrid Economy. New York: Penguin.

MacCormack, A. (2007, November 12). A Tale of Two Kingdoms. Retrieved December 1, 2008, from Adventure Gamers: «http://www.adventuregamers.com/article/id,819/p,2»

Manos, D. (2004, Aug 18). Interview with Rebecca Clements of Cirque de Zale. Retrieved Nov 17, 2008, from Just Adventure: Inventory 14: «http://www.justadventure.com/Interviews/Rebeca_Clements/Rebeca.shtm»

Reality-On-The-Norm. (2008). Reality-On-The-Norm. Retrieved January 5, 2009, from «http://ron.the-underdogs.info/»

Twelve, V. (2006, November 26). WLBSWHEAC Postmortem. Retrieved February 2008, 18, from Xii Games: «http://xiigames.com/2006/11/29/wlbswheac-post-mortem-part-one-concept/»