Narrative environments: how do they matter?

Allan Parsons

Abstract

The significance and possible senses of the phrase 'narrative environment' are explored. It is argued that 'narrative environment' is not only polysemous but also paradoxical; not only representational but also performative; and not just performatively repetitive but also reflexive and constitutive. As such, it is useful for understanding the world of the early 21st century. Thus, while the phrase narrative environment can be used to denote highly capitalised, highly regulated corporate forms, i.e. "brandscapes", it can also be understood as a metaphor for the emerging reflexive knowledge-work-places in the ouroboric, paradoxical economies of the 21st century. Narrative environments are the media and the materialities through which we come to comprehend that world and to act in those economies. Narrative environments are therefore, sophistically, performative-representative both of the corporate dominance of life worlds and of the undoing of that dominance, through the iterative responses to the paradoxical injunction: "learn to live". [1]

1. Clearing the way

[1] The conjunction of the two terms 'narrative' and 'environment' suggests a number of alternative understandings, depending on whether the former term qualifies the latter or vice versa: the environment of the narrative, "taking a stranger's word for the world" [2] (narrative as environment); or the narrative of the environment, "environmental discourse"(environment as narrative). Nonetheless, a narrative environment is both a narrative and an environment at once. It could fail on either or both narrative grounds or environmental grounds.

[2] For example, the phrase 'narrative environment' could be understood to mean that, in the course of our everyday lives, we are surrounded by stories: our own existential experience [3]; other people's life stories; the histories embedded in particular places; the unfolding of events within a particular moment in a particular place; or the bricolage of graphic and architectural signs distributed about a particular topography, indicating how it might be navigated. In this incision, narrative is 'that which tells' and environment is 'that which surrounds'. Following Ricoeur (1984), it might be said that narrative orients us in time; while environment orients us in space. Further, narratives are both the telling (plot or emplotment, the sequence of events as told, narrative discourse) and the tale itself (story or narrative structure, with beginning, middle and end) [4]; environments both surround (actively environ, enclose and condition) and are the surroundings (environmental structures, categories and entities) [5]. Exploring the conjunction requires exploring what it is 'to tell' and 'to be a tale'; and what it is 'to surround' and 'to be a (set of) surrounding(s)'; and what it means for all of these senses to be conjoined and, as we shall see, to engage one another reflexively.

[3] To reiterate and move on, as varieties of story, narrative environments impel, pervade and mediate our understandings of our everyday, experiential worlds. We orient ourselves within those worlds and actively navigate those worlds temporally (through narrative) and spatially (through environment) and spatio-temporally through narrative environments, processes that are not without their difficulties and contestations, i.e. they are reflexive accomplishments, as an ethnomethodologist might say. Thus, Garfinkel defines the central topic of his studies as, "the rational accountability of practical actions as an ongoing, practical accomplishment" (Garfinkel, 1984: 4) Within ethnomethodology and symbolic interactionism, our everyday practical accounts are not only reflexive and self-referring, but also constitutive of the situations to which they refer. These accounts may act to reproduce or transform those social situations.

2. Waylay: Wandering off

[4] The parallel, mimetic journey begins in Narrative Event 1 with a blurry, shadowy figure on the move, a linguistic shifter, a migrant body, a mere sign in a regime, a mere pawn in a game, carrying baggage, reflected and framed by the wall-window-mirror that the glass of the King's Library Tower forms.

Narrative Event 1

[5] The King's Library Tower, "one of the most significant collections of the Enlightenment, containing books printed mainly in Britain, Europe and North America from the mid-15th to the early-19th centuries" [6], is an unambiguous symbol of knowledge as cultural resource, on the one hand, and knowledge as property, as possession, on the other. The library belonged to George III, King of Great Britain and Ireland in 1760-1820, the sovereign individual in that territory for that period, before passing into public, national ownership. It is a performative symbol of what is being made available to the readership, the promise being that, as library members, they too can become sovereign individuals through possession of knowledge, gleaned from access to the books and journals in the nation's possession, and through that knowledge-possession become empowered, because free from tradition (religious and feudal social order) and prejudice (superstition, myth and magic).

[6] Thus, the topographic place opens out into narrative sequences, for example, a historiography of the nation as a collective body, a narrative of societal progress, or a biographical narrative of individual knowledge acquisition, a narrative of quest. It also opens out onto an historiographical narrative about the Georgian challenges of empire, extra-parliamentary radicalism, egalitarianism and cultural progress.

[7] The figure in Narrative Event 1 moves away from the stable, secure, more certain forms of the library, with its linear, ordered sequences and its taxonomic hierarchies, and its stairways for ascent from one level to the next. We are departing the World-as-Book, although not so much the Book-as-Bible as the Book-as-Encyclopaedia. We are stepping outside the circle of human knowledge as articulated in the language of the book as encyclopaedia because,

"...what we call language...now seems to be approaching what is really its own exhaustion; under the circumstances - and this is no more than one example among others - of this death of the civilization of the book, of which so much is said and which manifests itself particularly through a convulsive proliferation of libraries." (Derrida, 1976: 8).

This "death of language", this death of the civilisation of the book, is more properly, according to Derrida, a death of 'full speech', the cessation of the belief that, with the right interpretative tools, one can translate between the Book of God, or the Bible, and the Book of Nature, the world, reading the eternal truths of God's design from Nature back to the Bible, and vice versa. (Keep, McLaughlin and Parmar, 1993-2000: hfl0247)

[8] It is here that a metaphoric chain opens that likens narrative environments to an encyclopaedia. It runs knowledge-meaning-encyclopaedia-labyrinth-network-rhizome [7]. The semantic encyclopaedia, the encircling of the world by the story of knowledge, albeit broken into entries/episodes, in turn, becomes labyrinthine, which becomes network, which becomes rhizome. The sense of the metaphor is that narrative environments, as encyclopaedia, surround us with knowledge. A narrative environment becomes a knowledge-place. [8] That knowledge is in the form of a labyrinth, but a labyrinth of the network type, a network which continues to create new knowledge by making new connections in a network (like a rhizome). The encyclopaedia as labyrinth does not deny that structured knowledge exists; it denies only that such knowledge can be organised as a single global system, a single, Porphyrian tree of knowledge. A semantic encyclopedia provides only 'local' and transitory systems of knowledge, which can be contradicted by alternative and equally 'local' cultural systems.

[9] To extend this metaphor, a narrative environment, as an encyclopaedia entry, is a node of knowledge, but in the world, not in the pages of a book. It is part of a network of narrative environments. The sense that it makes is localised, contextualised, but also networked, globalised. Together, as encyclopaedia, as labyrinth, narrative environments encircle the world, but they form an inconceivable totality. It is in this sense that narrative environments enact order into the world, and orient us to the world, while the world as a whole remains an inconceivable totality.

[10] A narrative environment, as a planned and designed environment, does not reflect the truth of a planner's or a designer's intention nor the truth of the world. Narrative environments lack, and indeed do not aspire to, that sense of totality of the Book, as "a complete and unified structure that galvanises the polyvalency of language into a single, determinate meaning" (Keep, McLaughlin and Parmar, 1993-2000: hfl0247). While narrative environments play with and upon the narrative forms of beginning, relaying and ending, this is far from being a fascination with aetiology (origins or original causes) and teleology (finality or final causes) as a way of understanding the world. Narrative environments' reasons and purposes are far more limited, conditioned and conditional.

[11] Neither the Designer nor the Planner is the final link in the chain of substitutions that runs from Sun-God-King-Man-Language, the prime mover who does not move, the agent of change who does not change. Indeed, narrative environments halt the chain at the link 'King' and take it in a different direction, placing the King in an alliance with Parliament (State), on the one hand, and Capital (Money), on the other, as the seeds of Empire and Empiricism are disseminated.

3. "...the unlived life" (Davies, 2005: 216)

[12] 'Narrative' and 'environment' could be seen as two ends of a single spectrum. At the narrative end, the world is enveloped by culture, order established through material cultural artefacts. At the environment end, the world remains beyond cultural order in its presumed innocent, natural and/or wild state, order as the state or states of nature. Reduced to a binary opposition, narrative stands for culture, environment for nature.

[13] Having assumed a binary form, this opposition, culture/nature, could be elaborated using a logic of paradox, to enable perception of the natural within the cultural, for example, the urban zoological garden, and the cultural within the natural, for example, a battery-powered heart pacemaker in a human body. These forms displace the logic of identity/contradiction and open up the play of discursive forms which interweave chronological and logical order and create a deliberate confusion between temporal and spatial, sequential and consequential, consequential and causal, contiguous and necessary, correlational and identical, analogue more-or-less and digital either-or.

[14] The binary opposition culture/nature can be subjected to substitution such as, for example, by temporal/spatial, interior/exterior, superior/inferior, art/life, fictional/real or essence/accident. The environment, as spatial, exterior, inferior, life, real, accident, is that which environs the narrative: temporal, interior, superior, art, fictional, essence. However, this opposition itself may be subject to reversal, inversion, oscillation and revaluation.

[15] Thus, for example, "For [H. G.] Wells it is a question of choosing between doing art and doing life. But for [Henry] James doing art was doing life." (Kermode, 2007). The same is true for W. B. Yeats as for Wells, who, in his poem, "The Choice" asserts that "The intellect of man is forced to choose perfection of the life, or of the work". While, "[Ford Madox] Ford said he wanted to make the reader's mind pass 'perpetually backwards and forwards between the apparent aspect of things and the essentials of life'." (Kermode, 2007)

[16] In the words of Timothy W. Luke (1998),

"Many of the most important political debates in this generation center upon working through the practical implications in a handful of discursive dualisms: Nature/Society, Ecology/Economy, Environment/Organism. With each couplet, ongoing arguments contest the terms themselves: where one stops and the other starts, how the first limits the second, why each cannot exist without the other, what directives in the first guide the second, when the latter endangers the former are all questions sustaining innumerable intellectual exchanges."

In short, instead of simply surrounding as passive, exterior set of circumstances, the environment actively environs and conditions the interior, making exterior circumstance a condition of interior essence, as ground for action and decision, in a figure/ground oscillation. As Luke (1998) explains, one historical sense of environing is as a type of military, police or strategic action. To environ is to beset, beleaguer or besiege a place or person, in a strategic disciplinary policing of space.

[17] Following a paradoxical logic that starts from binary opposites, narrative environments are fictional realities and real fictions. Here, we are in the terrain of the double bind, as defined by Bateson (2000): we are bound both to narrative (fiction) and to environment (real), and both are reflexively constituted. [9] As explained by Wilden (1980: 202-229), following Bateson, the language of opposition is epistemological, a logic of contradiction, of either-or, while that of interpenetration is ecological, a logic of paradox, of both-and. [10] These binary oppositions, then, are not simply opposite sides but instead have the form of a Möbius strip, or perhaps an ouroboros, two figures often cited in the literature on paradox, one mathematical the other classical. [11]

[18] The phrase 'narrative environment', then, is not only polysemic but also paradoxical. It is a resource for discourse and for design practice, and the confusions which arise from its use are (endlessly) productive. It highlights the process of giving shape to the world, epistemologically, morally, materially and ontologically.

4."...I can't go on, I'll go on." (Beckett, 1959: 418)

[19] In the interpenetrative schema, the environment is a generative field, an "organised context within which inherited particulars act, and without which they can have no effect" (Hansen, 2000: 26, citing Goodwin, 1994). The environment and the narrative co-determine one another and adapt to one another, both formally constraining how that co-determined whole can develop, adapt, or 'evolve'.

[20] A more classificatory, taxonomic approach would seek to identify already existing examples of narrative environments, such as 'retail environments', which could be cited as an example of a kind of narrative environment. The environment here is a semantic frame, a part of a socio-cultural construct, a market-place realised in specific, concrete, materialised form, for example as a shopping mall, a high street or a street market, each with its variations and distinctions on a socio-cultural theme of retail commercial exchange.

[21] A market-place is but one kind of place. Place, an environmental term, may be understood as that part of the perceptible and proximate environment which is meaningful for the participants enacting that place. It is the significant context, the frame in which, and in relation to which, behaviour is oriented. That frame can serve both as environmental context, defining the boundary of place, and element in a narrative sequence, relating one boundaried place to other places narratively, whether topographically, dramatically, chronologically or logically.

[22] Burkitt (2005) notes that, for cultural geographers like E.S. Casey, a place is an arena of action that is simultaneously physical, historical, social and cultural. Burkitt interprets this as saying that a place is a historical, cultural and interpersonal context for action that gives action a depth of meaning. Thus, for Burkitt, "As arenas of action, places are constitutive of our sense of self, for they are the context of that historical agency of which biographies are composed." (Burkitt 2005: 106) In this way, a place is like a milieu, in the ecological sense, which Hansen (2000), following Varela, defines as, "the continually-shifting part of the environment which has existential meaning for an organism" (Hansen 2000: 19)

[23] Not all narrative environments operate as ecological niches, or 'lived places', however. The contrast between thick and thin, as utilised by Burkitt, may not be adequate to articulate what is at stake here, but it gives us another resource with which to think narrative environments: Are narrative environments 'thin environments' in some sense, in that they lack existential significance? They can inform or entertain, much like public broadcasting in the Reithian tradition, but can they provide an existential orientation and sustenance for the self? In place as ecological niche, the organism/person relies on the environment for survival in practice and on the continuing viability of the organism-environment relationship. In some narrative environments, the organism/person may be more or less well informed or entertained, but their survival does not depend, in any ongoing sense, on a continuing viable relationship between organism/person and narrative environment.

[24] For Burkitt, place and self are intrinsically inter-related. However, place and self need only be tangentially related in narrative environments, such as those in which one is a visitor or a temporary resident, at best. Narrative environments give on to 'visitor experiences' of different degrees, touching upon a sense of self lightly. If narrative environments were to work as ecological niches, there would have to be a plurality and a diversity, of different levels and different types, not just a multiplicity of, and within, the same, and such a diversity, given the unpredictability of the entire field of interaction, would be difficult to design or plan, or to know in advance.

[25] A narrative environment, then, could be defined as a situated narrative, or a site-specific narrative, like a piece of installation art, framed by the elements which establish place-hood or place-ness. It could be argued, indeed, that a narrative environment simulates place by giving a location a significance it otherwise would not have, for example a barn-like space becomes a cinematic-derived place of struggle with dinosaurs or small soldiers. A narrative environment, on this account, is not a 'genuine' place but a simulated place, a place at which the visitor has to work at constructing the senses and meanings to which the narrated experience points, but which do not come 'naturally'.

[26] This vocabulary, 'genuine' and 'naturally', is problematic and this distinction between 'genuine place' or 'lived place' and 'narrative environment' is troubling. It is too simplistic. It takes too much for granted, for example a time when experience was genuine contrasted to a time when it no longer is. Would it be better to say that a narrative environment is a meta-place, a place about what makes a place, the places of history, the places of literature and cinema, the places of commercial life, for example? However, this is also problematic. Narrative environments are places themselves. They do not simply depend on the existence of other places. They are not epiphenomenal, so to speak. Their mode of existence is independent, although different from that of an unreflective 'lived place'. Narrative environments are marked by the explicitness of their design, by the reflection on experience which has gone into their making. Something of this distinction can be seen in the relationship between the visitors to "Summerlee, the Museum of Scottish Industrial Life" and the residents of Coatbridge in Scotland, where this museum is located. As the reviewer of the re-opened museum notes,

"So here, on the surface at least, we have yet another attempt to capture and restore meaning to an industrially redundant community through a heritage regeneration project." (Johnson, 2009)

A lived place is open-ended, an inconceivable globality, constantly being revised in terms of its localised, but networked, narratives and goals. A narrative environment, like a literary narrative, in being designed from beginning to end, has a certain closure, a certain finality in terms of its meaning production, a limited goal, for example in relation to degree of participation in goal-setting. A narrative environment, it could be argued, has a control narrative, and that narrative, as effective management regime, is enforced and enforceable.

5. Waylay: erring warring

[27] Having departed the Age of Enlightenment of Narrative Event 1, we stumble upon the Age of Revolutions. Revolution, one might deem an archetypal performative-disseminative act, runs riot: Glorious [12], American, French, Industrial, Scientific, Russian, and so on.

[28] We become embroiled in the world as soldier, not as soldier of fortune though, but rather as soldier of ideology, as the spectre of a revolutionary violence, both in military (State and Empire) and in technological form (Empire and Science), a uniformed, collective, organised, corporate response to the established order, a determined overthrow of that order by another form of organisation (in this example, soviet, socialist).

[29] No longer are we in the World-as-Book, with its aetiology and teleology in God's will. We are in the World-as-Struggle, a Nietzschean world, a world in which there are antagonistic wills, each with a will-to-power. We soldier on, we take up arms (weapons and technologies), we move from the vita contemplativa to the vita activa (Arendt, 1958: 9). Now a revolutionary, empirical subject, we develop military strategies and technologies, based on the evidence before us, to pursue militant action against established order. We environ imperially and scientifically. Still trapped ourselves, however, we oscillate between taking revolutionary action and following orders, pursuing what is in our best interests, itself a paradoxical injunction, as we define and orient ourselves against The Other, The Opposite, The Opposition, the Enemy.

[30] In Narrative Event 2, then, while we have overcome totality (univocity, mono-semy), we remain with poly-semy, with choosing among and hierarchising existing meanings, existing orders, taking orders. In this event, we may be engaged in a reversal of hierarchies, but we are still far from recognising the narrative event as disseminative, as capable of creating new meanings outside of the existing binaries (Us-Them) and binary substitutes (Civilised/Primitive). Mysteriously and ambiguously, although dead, God is on our side.

Narrative Event 2

6. Looking within looking without

[31] One possible semantic equivalent for 'narrative environment', then, is place, itself a polysemic term. If it is an ecological place, it is one supplemented by insights from cultural geography. One possible interpretation of place is context; and one possible interpretation of context is system, or systemic whole, an information, communication, exchange and control system. Since this system involves life or mind, it is an open system (Wilden, 1980: 203). Place, as open system, exhibits and enfolds information, order, organization and improbability. Within such cybernetic open systems, causality is non-linear and circulatory and, as discussed, for example, by Bale (1998), there is a hierarchy of contexts.

[32] Open systems are Janus-faced. As a whole, the system faces inward. It is concerned with maintaining its internal steady state through its dialogue with itself. As a sub-whole, a differential part of a larger whole, the system faces outward, responding to perceived differences in its environment, a meta-system, and differences communicated to it through pathways or networks of recursive circuitry within the larger system, in a potentially infinite regression of relevant contexts. In this way, open systems operate both intrinsically (as a whole) and extrinsically (as a part-whole). Context is never 'total', "never absolutely determinable", or rather "its determination is never certain or saturated" (Derrida, 1982: 310)

[33] As Bale expresses it, a context is a non-substantial phenomenon, functioning like a map or a model. It is a recognition of the differences that make a difference within a set of relationships. Places are sets of interlocking processes and relationships, held in an ecological balance, which may be far from equilibrium, and which may be very precarious (Levin, 1997).

7. Volte face

[34] 'Narrative environment', then, unfolds as a series of metaphoric substitutions: place, context, system, model, map, and so on. Not only does the phrase 'narrative environment' not have a single, literal, 'proper' meaning, i.e. as noted, it is polysemic and paradoxical, but also it does not just describe or represent something but does something; it is performative. For example, it is not just 'a place' but also actively 'places' or 'puts in place', intrinsically and extrinsically; it is not just 'a system' but also 'systematizes', or organises; it is not just 'a context' but also 'contextualizes', or makes present through relating; it is not just 'a model' but also 'models'; it is not just 'a map' but also 'maps'. That is one of the ways in which its duality, its paradoxical, Janus-faced character is realised.

[35] In other words, narrative environments are not just sets of representations (signs), however polysemous or paradoxical, but also sets of performatives (acts); they are signs-acts [13]. Further, their form of action is reflexive: they bring into existence the signs/signatures that they sign, the events they enact; the contexts they environ. They are reflexive signs-acts-contexts, generative fields, that take place in the world and are of the world; they are not apart from the world.

[36] The word performative is not just ambiguous; it is originary, promethean and pandoran in its creativity and productivity. The word performative is performative: it does what it says, but what does it say?

[37] In the sense outlined by J. L. Austin, the performative is limited to conventional performances in ordinary circumstances, themselves part of a conjectured but admittedly impossible 'total context'. In this frame, performative (doing something while saying something) is contrasted with constative (stating something about the world that may be true or false). In this Austinian sense, a speech act brings into existence what it purports to describe, but what it brings into existence is conventional, proper, already recognisable and well understood, by those doing and hearing the speech act: the appropriate words are uttered, by the appropriate persons, in the appropriate order, with the appropriate intentions, to the appropriate others, under the appropriate circumstances. The examples Austin uses highlight this conventionality, bordering on rituality. They include, for example, the wedding vow and the naming of a ship. Thus, while the performative act in the Austinian sense does something, it does so as an act of repetition, an act that is already citational, in Derrida's terms. While in some sense constructivist, in as far as a performative utterance does not describe something which exists outside and before language, the contextual situation that it produces is recognisable as one that is structurally the same as others that have gone before.

[38] Derrida radicalises Austin's insights when he argues that,

"Every sign, linguistic, spoken or written (in the usual sense of this opposition), as a small or large unity, can be cited, put between quotation marks; thereby it can break with every given context, and engender infinitely new contexts in an absolutely nonsaturable fashion. This does not suppose that the mark is valid outside its context, but on the contrary that there are only contexts without any center of absolute anchoring. This citationality, duplication, or duplicity, this iterability of the mark is not an accident or an anomaly, but is that (normal/abnormal) without which a mark could no longer even have a so-called 'normal' functioning." (Derrida, 1982: 320)

Performativity, radicalised by Derrida (1982; 1988) has been extended by, for example, Butler (1993; 1997; and 2006), actor network theory (Latour, 2005; Law, 2007), Pickering (1995), Barad (2003), Thrift (2007), amongst others, to become a material, practical and an ecological concept, covering human and non-human performance and performativity, which are intertwined in socio-technical assemblages, or narrative environments.

[39] Rather than the performative as performance of the same (repetition), albeit through a chain of polysemous substitutes, Derrida proposes the performative as alteration, as dissemination, overturning the subordination of otherness (alterity) to sameness (identity) and effecting a general displacement of the system as a whole [14]. In this way, Derrida highlights, whereas Austin played down and, at times, tried to exclude, but of which he was well aware, the paradoxical nature and the riskiness of the performative, the possibility of meta-communication and the possibility of failure: performative acts may inaugurate, but they may destroy, and that destruction is beyond renewal as Schumpeterian 'creative destruction'.

8. Waylay: Delay decay

Narrative Event 3

[40] In Narrative Event 2, then, while we have overcome totality (univocity, mono-semy), we remain with poly-semy, with choosing among existing meanings, existing orders, taking orders, receiving injunctions. In this event, we may be engaged in reversal of hierarchies, but we are still far from recognising the narrative event as disseminative, as capable of creating new meanings outside of the existing binaries (Us-Them) and binary substitutes.

[41] We begin this part of the journey in Narrative Event 3. The wall, the boundary which divides the inside (Us) from the outside (Them), and the window, which establishes, frames and mediates the relationship between inside/Us and outside/Them, and which allows Us to see Them, becomes the focus of attention, a figure in what should have been ground. The event shows signs of alteration, or adaptation, in this case decay. The top window has lost its casement and glass; the bottom window has lost its shutters. The wall is discoloured from weathering and water run-off. [15]

[42] In Narrative Event 4, the iteration (it's still a wall, a boundary that divides), alteration (it, too, is decaying and weathering) and adaptation proceeds. No matter how solid the wall that divides, how smooth its exclusionary surfaces, it is unable to prevent cracking, to prevent plants from seeding themselves in those cracks, to prevent the outside (other as Natural-Biological Form, or Life) from infiltrating that which divides (culture; epistemology), creating a form of hybridity, a naturalised wall, a knowledge-place, an in-between that becomes a place itself, combining the well-formed surface geometry of the circle, of circles within circles, a parodic echo of encyclopaedic knowledge, with the adventitiousness of the fissure and the disseminated seed.

Narrative Event 4

9. Soldiering on.

[43] These qualities, representational and performative, are not inherent in narrative environments, but characterise their modes of relationship to the world, their contexts, while they continue to act in the world. Thus, a narrative environment may relate to the world diegetically [16], telling about the world, for example, a descriptive, historical narrative set in a museum; a narrative environment may relate to the world mimetically, showing aspects of the world, for example, in a re-enactment of a period situation within the context of a museum exhibit; a narrative environment may relate to the world poietically [17], making or producing something, for example, when diegetic and mimetic forms (i.e. forms of representation) are harnessed to the task of selling motor vehicles in a car showroom designed as a "transport experience" (making a sale, while producing a customer experience); a narrative environment may relate to the world praxically, for example, when diegetic and mimetic forms of representing and poietic making are harnessed to the action of informing and educating in a learning environment.

[44] From the above, it can be recognised that narrative environments designed to be representational-performances, i.e. whose purpose is to represent (to perform representations), employ both diegetic and mimetic means. In this, they resemble a (designed) game or a theatrical play, or a media construct in general, where the world is pre-scripted and delimited and the participants in the game know and accept those limitations, and where the there is clear distinction between the actors/performers and an audience [18].

[45] It becomes clear that poiesis, praxis, diegesis and mimesis are all forms of action (to make, to do, to tell, to show) that a narrative environment can perform. They are also forms of purpose that a narrative environment can serve. Performativity again doubled: to perform an action (intelligible intrinsically); to perform a purpose (purposeful extrinsically); purposeful, intelligible action. Furthermore, each form of action can be subordinated to the other, such that, for example, following Lyotard's (1984: 50) discussion of "the performativity principle", as he calls it, but is more accurately an "instrumentality principle", in higher education, praxis, diegesis and mimesis are subordinated to poiesis, so that they become forms of production, capable of productivity improvement and knowledge creation is reduced to production skills. Thus, what characterises any particular narrative environment is not that it exhibits any single one of these forms of action but the way in they are arranged and hierarchised to form a generative field; and whether that hierarchisation is rigorously enforced or loosely structured. In addition, they differ in the way the way in which any particular narrative environment is networked; and in the materials and media through which it is realised.

10. Under way

[46] In relation to an environment as proximate setting or set of surroundings, to adopt that sense for a moment, narratives may be inscribed in or through the surroundings or imposed upon them, or a mixture of inscription and imposition; narratives may be interactive or immersive, or a mixture of interaction and immersion. Immersion may be embodied or centred on the eye, as trompe l'oeil optical illusion.

[47] An immersive, trompe l'oeil narrative environment structures the entire world of experience through the eye, generally employing a screen, subjecting the whole body to visual effects. An immersive, architectural narrative environment subjects the whole body to a particular form of experience, such as, for example, space flight simulation. An inscribed, interactive, immersive, narrative environment enables simulation and substitution of the life-world, an alternative world in a very limited sense, raising questions about the environmental, social, economic and political conditions which sustain the simulation, in other words, the framing of the frame or the contextualisation of the context.

[48] If a notion of space is at play in narrative environments, it is that of topographic space, combined with the differing, deferring, layering and reflexive returning of performative action: spatialisation realised through place and practice. In other words, narrative environmental space is not primarily visual, analytical, coordinate space, not Cartesian, Newtonian and Liebnizian, not perspectival, centred on the eye-as-I, first and foremost. It is a space of practice: spatialisation taking place and making place. There is no opposition here between territorial space and cyberspace. Spatialisation (environing; showing) and temporalisation (narrating; doing) of practice may involve information and communication technologies (ICTs), extending territoriality and power over territory, while altering notions of territoriality as contiguity, instead becoming contextuality. [19]

[49] What becomes interesting is the degree to which the 'reader of the inscription' is so immersed in the unfolding drama/narrative that they become identified, through introjection, with the 'inscribed reader' or, further, with the characters of the 'dramatis persona' in question. This relates not only to the sense of immersion, which here is related to the ego of the reader, but not necessarily the eye of the reader, but also to the sense of inter-subjective presence realised fantasmally through the drama and to the sense of reflexivity, distantiation or disjunction. How conscious is the reader of the potential identification taking place? The becoming-subjective of the inscribed reader reflects the extent of immersion-identification, or lack of reflexive distantiation at play in the mediated interaction, technologically rehearsed.

11. An other way

[50] Practices, as fields of performative enactment (representational, interactive and contextualising; diegetic, mimetic, poietic and praxic), form the environment in and through which the human (organism) and the social (collective being) are developed and sustained (social ontology); while practice itself forms a resource-environment, a material and behavioural environment from which elements of practice can be both borrowed and returned in the creation of practical organisation; and, in so doing, re-storied and varied.

[51] Within such domains as 'retail environments', narrative environments become nodes in the experience economy, and the design of narrative environments becomes an aspect of user experience design. The term experience economy, first used by Pine and Gilmore (1999) to identify an emerging level of marketing that goes beyond service and product image giving access to a sustained enjoyment of consumption, has been taken up most avidly by providers of total experiences, such as theme parks and museums.

[52] Sandy Isenstadt comments that "the very proliferation of themed environments betokens an emerging mode of architectural reception: serial immersion in narrative environments, itself an effect of an emerging experience economy." (Isenstadt, 2001: 109). Serial immersion in narrative environments, he argues, is more and more looking to be the shape of daily life, such that daily experience takes on a scripted quality (Isenstadt, 2001: 117). Thus, "an individual may become differentiated by her or his path through environments", and "the self is itself now put together as it moves through a series of themed spaces" and the "environment takes on a shaping agency and the human subject is its chief artefact." However, "the individual in the themed environment, despite appearing as a protagonist, treads a narrow and pre-figured track". (Isenstadt, 2001: 117)

[53] In this context, with "daily life turning into a series of settings and scripts, buildings turn from being more or less neutral backdrops to human life to becoming agents in the actuation of scripts" (Isenstadt, 2001: 117). An extreme consequence of this might be that themed environments "dissolve consciousness of self as anything other than being a protagonist in a script." (Isenstadt, 2001: 117)

12. Recess

[54] While narrative environments may be understood as nodes in a putative experience economy, the phrase can be seen to link 'experience' and 'economy' in another way. The 'economies of experience' are organised around embodied selves, the production, enaction and alteration of subjectivity (subjecthood and subjection). The experience economy is organised around markets; the production, distribution and delivery of goods and services as experiences. In this context, narrative environments are that which inter-relates and integrates the 'economies of experience' with the 'experience economy', the doubled production of selves and markets; and while the economies of experience can be disciplined by the experience economy, the former cannot be reduced to the latter without residue. That is to say, the production of subjecthood cannot be reduced to total subjection and remain an experience economy. It becomes instead a slave economy. The experience economy implies choice and limits or restricts choice. It does not do away with choice.

[55] Randall and McKim (2008), taking their lead from Bruner (1990), take the primary sense of the phrase 'narrative environment' to be "any context in which we talk about our lives, whether to others or ourselves" (Randall and McKim, 2008: 50). They take 'narrative environment' to be equivalent to 'discursive environment'. In other words, any verbal utterance is contextualised by a discursive environment, the utterer's discursive repertoire in relation to how it organises the utterer's meanings and actions, on the one hand, and in relation to the listener's discursive repertoire, on the other.

[56] The secondary sense in which Randall and McKim understand the phrase 'narrative environment' is "the actual collection of written and oral narratives – of movies and novels, jokes and rumors, gossip and news – that we move within each day" (Randall and McKim, 2008: 50). While this extends the previous sense beyond the direct interpersonal contact of utterers and listeners, it retains 'discursive environment' as the contextualising frame. This means, from the position being developed here, we must agree and disagree when they state that,

"Given that we are languaged creatures, our sense of self necessary evolves within narrative environments." (Randall and McKim, 2008: 50)

We are not just languaged creatures, if languaged means linguistic. We are linguistic creatures contextualised by embodied semiotic creatures contextualised by materially networked creatures: our language utterances, or speech acts, are framed by embodied acts in determinate designed, architected, immersive, material-cultural-environmental contexts. We perform sign-act-contextualisations, a complex field of action in which part of the performativity is delegated to the material-cultural-environmental contexts, so that, in a sense, we can pick up where we left off without having to establish the grounds all over again each time we interact. In short, narrative environment is not limited to linguistic-discursive environment.

[57] While the therapeutic situation often focuses on isolating this linguistic-discursive environment, in various forms of 'talking cure' or bringing to linguistic-dominated awareness, proponents of the experience economy recognise the wider, embodied, environmentalised, the dual, conditional inside-outside, semiotic experience of the self. Thus, while Bruner's insight is crucial, that "All narrative environments are specialised for cultural needs, all stylise the narrator as a form of self, all define kinds of relations between narrator and interlocutor" (Bruner, 1990: 84), that narrative environment needs to be extended semiotically and bodily (from linguistic to non-linguistic, embodied forms of inter-action) as well as contextually (from linguistic-discursive environment to the designed, architected, shaped material-cultural environment).

[58] Understanding narrative environment in this way, while still allowing its central relationship to sense of self, first, enables recognition of how it might be feasible in the new "servicescapes" and "brandscapes" of the experience economy for employees to be "charged with the task of producing "fundamental units of experience" that the consumers will want to "take home" as souvenirs" (Strasser, 2003: 30). It also becomes feasible to understand such brandscapes as being organised around the self, around the market and around the integration of self and market. In the context of the self, brandscapes are understood by means of the so-called Diderot effect, whereby people learn to create ensembles of possessions, such as clothes and home furnishings, that amount to a self-brandscape (Knox, 2008: 143-144). In the context of the market, a brand and its brandscapes constitute a belief system in which "Authenticity breeds belief (culture). Belief breeds belonging (community). Belonging breeds loyalty..." (Hanna and Middleton, 2008: 61). In this way, access to the self, and self-betterment, (as purchase and assembly (consumption) of goods and services to create a self-brandscape) is enabled through access to the market (as presentation and provision of branded goods and services in branded environments with high status or prestige value).

[59] Second, it becomes easier to comprehend this triple production of selves and markets and environments as "experiencescapes" (O'Dell and Billing, 2005: 15). Rather than limiting interaction to the linguistic-discursive environment, those who create experiencescapes "focus upon the spaces and materiality of experiences" (O'Dell and Billing, 2005: 16). In this way,

"As sites of market production, the spaces in which experiences are staged and consumed can be likened to stylised landscapes that are strategically planned, laid out and designed. They are, in this sense, landscapes of experience - experiencescapes - that are not only organised by producers (from place marketers and city planners to local private enterprises) but are also actively sought after by consumers' (O'Dell and Billing, 2005: 16)

O'Dell and Billing use the term 'experiencescapes',

"in order to underline the degree to which the surroundings we constantly encounter in the course of our everyday lives can take the form of physical, as well as imagined, landscapes of experience." (O'Dell and Billing, 2005: 15)

The self, as 'economy of experience', can be seen in this way to be inter-related, and to varying degrees integrated, with the 'experience economy', with 'experiencescapes' serving as the interface enabling access to the highly capitalised, knowledge-based economy. A narrative environment, then, may appear to be such an experiencescape, but a narrative environment, in drawing on the 'economy of experience' may also incorporate learning beyond that of learning how to operate in a brandscaped-experiencescape. It may also draw on lifelong, adaptive learning, which brings to awareness choices and decisions that lie outwith the domain of brandscaped-experiencescaped consumer choice, focusing on the ecologies upon which the imaginary communities of such brandscapes-experiencescapes depend: the production of markets (flows), on the one hand; and the production of places (spaces or punctuations of flow), on the other; and the relationships of the self, now understood plurally, to the production of those (globalised) flows and (dispersed, disjunctive) places.

[60] As O'Dell and Billing indicate, while the thought of Arjun Appadurai may be useful for understanding the production of markets-flows, through his characterisation of landscapes of shared knowledge (mediascapes, ethnoscapes, ideoscapes, financescapes and technoscapes), his thought, in turn, needs to be supplemented by a consideration of the production of space to which these flows are related and through which they are grounded and contextualised, such as can be found in the work of Henri Lefebvre. Thus, Appadurai (1990) draws attention to the ways in which experiencescapes are linked to transnational flows that distribute (techno-scientific) knowledge and (political-financial) power asymmetrically, which has major implications for the ways in which we perceive our selves and the ways in which we act on the basis of such perceived identities/relationships. Lefebvre (1991), who is also very conscious of issues pertaining to knowledge and power, focuses attention more closely on the ways in which such spaces of production and consumption are organised as sets of networked places (emitting and receiving places in a field of flows), in terms of their designed/architectural, mental/cognitive and social/networked elements.

[61] The application of Appadurai and Lefebvre allows us to recognise that while brandscapes, servicescapes and experiencescapes operate in many ways like narrative environments, the former three terms are not co-extensive with the fourth; while the work of Bruner and Randall and McKim enables us to envisage ways in which narrative environments empower selves that are not solely those of the experience economy, selves capable of lifelong and adaptive learning, of carving other paths, of forming other relationships, of shaping other experiences. This opens up an understanding of narrative environments as 'economic landscapes' through the metaphoric chain: landscape-brandscape-servicescape-experiencescape-experience economy-economies of experience-learning economies.

13. Waylay: Erosion

[62] The hybridity of Narrative Event 4 is redoubled in Narrative Event 5, where the natural wall of the hillside, re-carved by man-made cuts, is mimicked by the brick wall of the building, weather-beaten (ageing-learning), the windows remaining, broken and decayed, to distinguish a building (wall) from a natural form (cliff-edge), subsequently overgrown and infiltrated by disseminated plant life to form one single natural-geological-organic-inorganic-carved-constructed-cultural whole, a narrative environment surely, but not planned, not by design, not by intention, but instead a succession of iterations.

[63] Where the hills are less precipitous, as in Narrative Event 6, the built environment proliferates. It forms that 'second nature' of the urban-form, the Urban Revolution, [20] creating both (territorial) sprawl and (atmospheric) haze, contrasted to Narrative Event 7, where the environmental product of agricultural and pastoral activity yields a lucid clarity.

[64] We live in Narrative Event 6; we vacation in Narrative Event 7, and tell ourselves different stories when we are in each location, using environmental, climatic and atmospheric props and tropes that give us our cues and to relay our stories; and we tell ourselves yet another story to explain why we need both environments in a 'work-life balance'.

Narrative Event 5

[65] Narrative Event 8 re-marks and begins to cover over "the birth of civilisation" in writing, agriculture and, in this case, the wheel. The wheel now appears as a museum piece, representing a past we have in some sense transcended, the landscape and buildings appear as if they were the accoutrements of an open-air museum, of which Narrative Event 7 is also a part. Even though they are still part of a 'working farm', part of an Agricultural Revolution, they are not part of the current knowledge-based agri-business, the Agricultural Revolution reworked by the Industrial Revolution and the Scientific Revolution, to form a Bio-Technology Revolution.

Narrative Event 6

Narrative Event 7

[66] Presented with a landscape, which is now inescapably both a perceptual (a form of action) and a pictorial experience (a form of representation), of agricultural fields, hedgerows and pathways, the landscape/picture does not so much tell a story, for example of rural, agricultural French life, as present elements from which people can make a story, to create a historiographical narrative, as with, for example, Narrative Event 7: a prior economy of production and experience displaced by another, agriculture by tourism. A landscape, without doubt, can be a place and it can be made to tell a story, but that story has to be worked up from a few scattered elements. It is a narrative environment only in a weak sense. In a narrative environment in the strong sense, the story or stories are more conspicuously evident, as are the conjunctions and qualifications which move the stories in particular directions, which inflect the stories.

Narrative Event 8

14. Any old way?

[67] People make things: poietic performativity; humankind as homo faber. Most importantly from the perspective of narrative environments, people make stories, people make places, people make one another (relationships; interactions; contexts; environments) and people make themselves (identities in relationship and interaction, in place and in the narrated self).

[68] Stories, places, interactions and selves, articulated in practices, are four of the main ways in which people make the world intelligible, by making their actions and behaviour intelligible to themselves and to others, by recognising others' actions and behaviours intelligible, orienting relationships and expectations; by making the more abstract and impersonal world of institutional relationships intelligible; by shaping the material world into cultural artefacts and devices; and by shaping the processes of the biochemical, biophysical material world, including their own bodies, towards humanly and socially performative ends.

[69] Stories make the world intelligible; places make the world intelligible; interactions make the world intelligible; selves make the world intelligible; all mediated through the place-environment of the body, with its introjections from, and projections into the built environment, and the networked collectivities of embodies selves. They make the world manageable and navigable for embodied intelligence. They stabilise experience. They create the bases for understanding personal and social accountability, for grasping roles and responsibilities at different scales. They create expectations, they establish a degree of predictability. They permit thought about futurity, about possibility, probability and desirability. They permit explanation. They ground ethical behaviour in thought (narrative, story, explanation, account) and in body (embodied cognition, enaction of self awareness through thinking-thought). Narrative environments, as designs, explore and exploit those dimensions of intelligibility: they can be used commercially to exploit experience; they can be used critically to examine experience.

[70] Stories are the means by which one understands one's place in the world: habitat or niche (ecological place); interpersonal roles (familial and communal place); societal roles (political and economic place); and sense of embodied self (individuated place and imaginary place). Crucially, they are also the means by which one can alter one's place, in whichever sense desired, by taking or exploiting one's opportunities, by recognising opportunity. [21] This is one way of characterising the struggles in which people are involved existentially and experientially.

[71] However, while stories, places, interactions and selves make the world intelligible, manageable and navigable, they do so in different ways. They are all performed, but through different kinds of performance and performativity, some grounding and environing, others iterating and altering. In many ways, selves bridge stories, places and relationships through performative interaction, sensing and acting to heal emerging incoherence, but, even so, the self is not a constant.

[72] All four domains (story, place, interaction, self) give order to the world, to body-environment systems, impose order on the world, while being sensitive to the pre-existing order in the world and to that which escapes order, the unpredictable, the unmanageable, the conditional-environmental.

[73] Story, place, interaction and self are ways of making sense [22]. They are also ways of making order. What is the difference between making sense and making order? Order seems to imply a sense-in-common, a common sense, an order recognised by members of the commonality or community. Sense by itself seems to have the possibility of being fantasmal or fantastic, belonging to the self alone (making sense to me, making sense of me), related to the psycho-somatic experience of the self. How does one adjust these psycho-somatic senses to the communal order? Order also seems to imply a sense that persists. Sense by itself may be fleeting but nonetheless sense-ible. Order endures. It is that persistence that is of interest. How does sense-in-common persist through order and organisation? Part of the answer would be: through narrative environments.

[74] It could be argued that people are obsessional in making things and making relationships, and that in so doing they continually re-make, and in re-making they not only repair or restore, they also destroy. People destroy things and, more importantly, relationships. That is an important feature of humankind as homo faber.

15. Ways and ends

[75] Narration not only creates sense/non-sense and order/dis-order but also opportunity or opening, a turning point, a self-defining moment, in rhetoric, kairos, the right time, the opportune moment, not just the chronological moment as that which passes sequentially before and after.

[76] A narrative environment is a Janus-faced performative environment, i.e. a practical environment and an institutionalised environment. For Alastair MacIntyre, a practice is,

"any coherent and complex form of socially established cooperative activity through which goods internal to that form of activity are realised in the course of trying to achieve those standards of excellence which are appropriate to, and partially definitive of, that form of activity, with the result that human powers to achieve excellence, and human conceptions of the ends and goods involved, are systematically extended." (MacIntyre, 1985: 187)

[77] The key aspects of practice for MacIntyre are that they are communal endeavours; that there is a distinction between internal and external goods; each practice is defined by standards of excellence which determine the goal of the activity and regulate its internal operation; and a practice requires not only individual virtue but also a supportive, i.e. institutional, context. (Breen, 2008)

[78] MacIntyre makes a distinction between practices and institutions. For MacIntyre, institutions, whatever their form, such as, for example, laboratories, hospitals, universities or crafts guilds, are concerned with external goods. External goods are the generic goods of money, power, status and prestige. Internal goods are specific to a particular practice. They can only be known and achieved through sustained engagement in the practice itself. Excellence in performance and excellence of the product are distinguished from the wealth, fame or power that may contingently accrue. Since practices and practitioners require money and material resources, they cannot exist without institutional frameworks.

[79] This institutional dependence leaves practices vulnerable being subordinated to the production of external goods at the expense of excellence. In terms of our Janus-faced, performative scheme, narrative environments as domains of practice (internal system as whole) may be subordinated to institutional constraints (relation to larger whole). Opportunity becomes opportunism.

[80] Disillusionment, as a result of such infiltration, is as much a part of narrative experience as is the pleasure derived from creating order, in experiencing pattern, in simulating practice for a particular effect and in playing with forms of intelligibility aesthetically.

16. Waylay: Entangle

[81] In Narrative Event 9, the surfaces of the growth of centuries of industrial economy are given over to lichens. As we do not recognise ourselves in the image, it shows how little we understand of the emergent ecological economy into which we have strayed, as if by accident, but always as a result of planning and design. The lichen is a compound organism, two separate plant-like organisms living together, algae and fungus, each helping the other to survive. Algae and fungus exist separately in the natural world, but in lichens they come together to create a single living thing, living symbiotically on the surface of things. Furthermore, lichens do not have roots. Their root-like structures, rhizomes, merely anchor them in place (Cornish, 2002). However, they are not parasites. They do not live by causing harm or removing nutrients from their host. They are epiphytes, using their host solely for support.

[82] The metaphor of lichen-human can be developed and extended, but it also breaks down. If the rhizome is a metaphor for the structure of 'knowledge', an encyclopaedia in labyrinthine form, an inconceivable globality, in the case of the lichen the rhizome/knowledge anchors the lichen in place; whereas people can 'pull up anchor', they can 'uproot themselves', the rhizome/knowledge detached and re-attached elsewhere, in another place, a displacement that may or may not prove successful. Thus, like lichens, people have no roots, they only have rhizomes/knowledge that anchor them in place in the world as encyclopaedia, but unlike lichens, people's rhizomes/knowledge are retractable, enabling them to migrate from place to place. There is another difference. Lichens are not parasites, unlike people, who do cause harm and remove the nutrients from their host environments. Narrative Event 6 can be reinterpreted in these terms. The city is lichen-like in as far as it covers the surface of the earth and puts down 'rhizomes', cultural markers and building foundations, grounding it, but it is not lichen-like in as far as the city is parasitical upon its host environment.

[83] There is another place where the metaphor can be put into play and put in question, perhaps instructively. Lichens are symbionts or symbiots. Might it be worth considering people as symbiotic, as being (at the very least) two animal-like organisms living together, one human the other social, mind-in-body (organism-self and self-consciousness awareness) and body-in-mind (contextualised social and cultural subjectivity and subjection or objecthood), each helping the other to survive? The brain, as narrative environment, serves as the matrix or interface between the one that is integrated symbiotically with the complex internal ('natural-biological') environment of organic life (mind-in-body); and the other which is integrated rhizomally through the sensori-motor systems to the external worlds of social life ('natural-material', 'natural-built', and 'natural-social'). [23]

[84] Thus, a journey which began with the lexicon of sovereignty, in Narrative Event 1, has shifted ground, away from unity, autarchy and immateriality, and towards the vocabulary of the symbiotic the rhizomic and the parasitic in Narrative Events 6 and 9. These signposts, maps, or models, Narrative Events 1, 6 and 9, the knowledge-rhizome, the urban-rhizome and the eco-rhizome (i.e. ecological-rhizome plus economic-rhizome), are our guides for the next part of the journey, showing the principles of the performativity of narrative environments ahead, re-marking the narratives and the environments we have lived by. Maintaining an imaginary sovereign identity, we are within the experience economy, struggling with the economy of work experience, as repetitive performance (work as labour, but a strange labour based on debt and consumption; the poietic economy) as performative alteration (work as engaged, creative, critical endeavour; the museographic economy), and as disseminative contextualisation (creating and destroying economies, ecosystems and environments; the ecological economy).

Narrative Event 9

17. The way is the end

[85] It is here that we can begin to conceive of narrative environments as reflexive knowledge-work-(work)places. Knowledge-work-(work)places subject the domains of story, place, interaction and self, and the sensemaking and order-making capabilities they harbour, to a double discipline: a critical, reflexive engagement, based on prior and ongoing learning (the learning economies); and a contractual, positivist engagement, based on employment and monetary agreements articulated through the financial, knowledge-based and experience economies. Such knowledge-work-(work)places are where selves (self-conscious awarenesses, subjectivities), communities and polities (selves in interaction) and economies and ecologies (of production, of experience, of knowledge, of place) are realised through work and material practices.

[86] The three previous metaphoric chains, i.e. knowledge-meaning-encyclopaedia-labyrinth-network-rhizome; place-context-system-map-model; and landscape-brandscape-servicescape-experiencescape-experience economy-economies of experience-learning economies, are supplemented by a fourth, possibly ouroboric, chain inserted among them, the seeds of which have been scattered throughout the preceding text-act-context: production-labour-work-performance-performativity. It is the surface of a barely concealed secondary chain within performativity itself: action-poiesis-praxis-diegesis-mimesis-representation-reproduction-consumption.

[87] Work in the 21st century often takes the form of a pre-scripted performance, both in terms of bodily actions and speech acts, not only for actors on the stage or in the cinema but also for others, such as, for example, call-centre workers and tele-sales personnel.

Narrative Event 10

[88] For example, in Narrative Event 10, the two women and the man are performing a task. They are making dim sum, quickly and skilfully, using manual dexterity. In other words, they are performing manual labour. This is, of course, not the typical image of manual labour, which is more usually represented by men doing construction work.

[89] They are also performing a role in the sense of consistently making the dim sum over a period of time, being a productive employee (contractual relation). More than that, however, they are performing a role in the sense that, being in a shop window, they are putting on a performance, a show, of performing manual labour. They are representing or citing themselves as manual labourers, while being manual labourers, for the audience of passers-by-tourists. While this is doubly a performance-performative field of action, these women and man are labourers not performance artists; their subjectivity is in the form of a subjection to the discipline of organised work, it is not an aestheticised expression of their subjecthood, even though it can be 'consumed' as such in an 'experience economy'.

[90] This opens up two economies, two circulatory flows: the making and the consuming of dim sum; and the making and the consuming of images, appearances, representations or citations in the form of performances. Both are everyday economies, everyday forms of action. The first is the more literal identification of consumption as the purchasing and eating of foodstuffs. The second is the more metaphorical identification of consumption as watching or looking at an image or performance. Both economies require skill and knowledge, knowledge of the phronetic kind, practical wisdom, that may be explicit or may be implicit. Both economies are doubly performative, in as far as they are both productive (making goods and making images) and consumptive (eating and watching).

[91] In performing doubly, the manual labourers are already providing an element of a third economy, a service economy, enhancing food retail with other qualities, such as visual entertainment for passers-by. This introduces a third level of performance, performing a service, sustaining a service economy. Furthermore, through that triple performance (making goods, making images, providing service relationships or interaction), they are well on the way to providing a fourth performance: providing a memorable experience, in Pine and Gilmore's terms. They do this by providing images which can be captured, in this case through photographic recording, as a picture by means of which to remember a performance of performing manual labour in support of performing a service economy in which the person taking the photograph is implicated.

[92] Furthermore, this image itself can be reproduced, as it is here, in a yet further turn of the experience economy by means of which that image is contextualised not just by nostalgic reflection (I remember that scene; I remember 'me' at that scene, Pine and Gilmore's memorable experience) but to critical examination or reflexive, analytical labour (a re-working of that scene in the learning economies): what was I doing there, in what kind of performative action was 'I' engaged; and therefore, who was 'I', then and there? For example, 'I' only 'intended' to buy and eat a dim sum; yet 'I' find myself partaking actively in the production and re-production not just of a localised economy (the making and consuming of dim sum; the making and consuming of a 'live' performance) but also of a globalised production and reproduction of images, appearances, citations, performances and the production and reproduction of a globalised 'self', whose performative actions outrun that self's limited understanding of its own 'intentions' at every turn. [24]

[93] Yet it is only through recognising 'intentions', their limited relevance and massive irrelevance, that 'I' can change my behaviour, my repertoire of performative actions, at different scales, in different contexts, and in that way alter 'our' world. Knowing what you are doing, who you are, becomes a matter of environmental awareness: how are your actions contextualised, and how multiple is that contextualisation? Everywhere, every moment becomes a knowledge-work-place, in other words a narrative environment, in which selves, realised through knowledge, work and place, as creative or inventive workers, [25] are reflexively engaged in multiple economies (circulations; calculations) and ecologies (de- and re-contextualisations). The knowledge is phronetic; the work is performative; and the place is continually de-and re-contextualising. In that way, narrative environments, as reflexive knowledge-work-places, are the fields, barns, workshops, ateliers, laboratories, factories, offices, warehouses, shops and market places of the 21st century economy, places where knowledge is deployed and which embody knowledge; where work is done; where selves are sustained and entertained; where purposeful action, based on critical reflection, becomes possible.

[94] The women and man, the manual labourers, in Narrative Event 10, are acting in multiple frames, and we are all still manual labourers at some level, at the level of typing, for instance. Through work as manual skill, they are making themselves as subjective identities, in MacIntyre's sense of practice as excellence, achievement. Through being part of a work organisation, as employees playing a defined role, they are making themselves as social subjects, having external or exchange value. Through making appearances, they are making themselves as body-image (introjectively) and as meta-communicative performer (projectively). While being engaged in localised performative productivity (the making and selling of dim sum; the making and consuming of performed images) they are also engaged in globalised performative productivity (attracting tourists and tourist spending; attracting tourist recording and circulation of images; and therefore yet more tourists). They are also engaged in performing female and male, gendered identity; and in performing ethnic Chinese national identity; and in performing class identity (labouring class, manual labour, manufacturing labour, catering labour). In other words, they make, tell, do and show all at once. They are thoroughly, multiply performative, in a thoroughly, multiply narrative environment, in a throroughly, multiply reflexive context, far beyond what any of them intends.

[95] The extension of human being into the world, through identifications (projections and introjections) and relationships (interactions and performativities), binds material otherness and other beings together in place and binds the body to place, however temporarily, and it does so performatively, and that performativity is rhizomic or labyrinthine in character. One of the primary ways that we have of understanding that complex, networked, generative field is narrative. How those projections, introjections, interactions and performativities (contextualised performances and disseminative performances) are stabilised in practice, as dual interiority and exteriority of performative context, determines both embodied experience and the economies of experience upon which the experience economy plays.

[96] The lineaments of this over-determined, deterritorialised performativity, which is nevertheless an arrangement between territorial states (as land-place and citizen-populations) and their formalised relationships (the law of the land; the law of property; the law of contract), on the one hand, and corporations (organised performances as productive labour, in the production of capital, for capital) and their rules and procedures (the laws of the market), on the other, can be seen to emerge with the period beginning with the Glorious Revolution, when future taxation (national debt), i.e. the population's anticipated productivity, comes to stabilise monetary, credit and debt relationships (i.e. possible futures and determinate pasts), and to manage risk (unpredictable eventualities; the incomprehensible totality of performativities).

18. Way beyond way back

[97] The traditional territorial and corporate factors of production, i.e. capital, labour and land, although far from irrelevant, no longer make sense. They are at odds with themselves and with each other in the reflexive knowledge-work-place, a trebly un-natural world, developing upon the un-natural productivity growth of agriculture and the de-natured productivity growth of industry. If science, technology and finance dominate our understanding of our world, how it works and the limits of what can be done, our conceptions of reality and necessity and of verifiability and verisimilitude, then narrative environments might just be the means by which we can come to understand the multi-layered, multiple and paradoxical performativity of the practices of science, finance and technology and their distinctive dynamics in the psychopathology of the everyday.

[98] In that sense, narrative environments do go further than simply informing or entertaining. Understanding narrative environments becomes crucial for our survival, as species of embodied, individuated, social beings, with a capacity to distinguish between imaginary and real or epistemological and ecological. Following Otter (2007), we could say that narrative environments are techno-social assemblages, arrangements that one hooks oneself up to, or attaches oneself rhizomically, in order to establish routine bodily capacities, a sense of empowerment; arrangements that make the world comprehensible. [26] Through narrative environments as experiencescapes, we are attached to scientific, financial and technical rationality, as consumers. However, through narrative environments as learning economies we may learn how to restore reflexive capabilities to reductive, self-contextualising, positivist rationalities.

[99] A narrative environment, in one strong sense, then, is a highly managed, highly regulated and highly capitalised place, a branded, corporate environment, a brandscape or experiencescape, signifying the dominance of life-worlds by corporations, as discussed by Bakan (2004). This applies to ourselves as much as architectural spaces: our assumed identity can become the brand which we repeatedly perform. However, in another strong sense, a narrative environment is that which enables us to understand how the paradoxical performance-performativity-productivity of that highly managed, highly regulated and highly-capitalised place works in practice. It is that insight which may enable us to rearticulate it, re-work it, to re-write the narrative; and change the 'nature' of our performative capabilities.

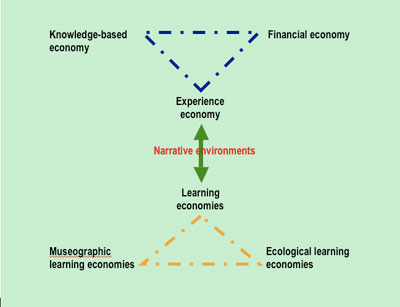

Diagram 1: Narrative environments in the 21st century ouroboric economies

[100] We are seeking here to undo a double bind in which we continue to harm ourselves even though we see ourselves as continuing to perform 'successfully' and 'convincingly'. The network role that we assume (introject) as an identity (brand), as we continue make ourselves and perform in our own image, is destructive of our bio-ecological bodies (selves and places) and the body of knowledge (phronesis) accumulated through practice (work). All of which is displaced by the making and consuming of images, representations or signs at ever higher levels of 'context-less' or 'self-contextualising' abstraction, i.e. increasingly impossible sequences of abstract calculation (scientific, technological, financial) that collapse in on themselves when punctuated by context.

[101] What counts as 'success' in a corporate narrative environment, dominated by the production of external goods in MacIntyre's sense (wealth, status, power, prestige), is not that it supports senses of self or provides living beings with a habitat, niche or milieu, which are incidental and largely fantasmal, but that its accounts show profit and, over time, show growth, and that its account of itself shows that profit and growth indicate that, as a narrative environment, it is competitive, particularly against narrative environments in the same market, that is, similar kinds of corporatised places. Finally, as part of its account of itself, the corporate narrative environment purports to show how it has indeed accounted for the risk of collapse inherent in its self-contextualising, abstract accounting system. Thus, as already noted, these capitalised 'productions' are complex fields of (largely pre-scripted) performance, often in the form of consumption, that limit (disseminative, potentially creative) practical performativity. They are acts of convincing through repeated assertion.