Storymapping: Exploring the Naturalists' Sense of Place

David MacLennan, Donald Lawrence, and W.F. Garrett-Petts

Our bodily experience of movement is not a particular case of knowledge; it provides us with a way of access to the world and the object , with a 'praktognosia', which has to be recognized as original and perhaps as primary. —M. Merleau-Ponty

Invitation to participate in the Tranquille project.

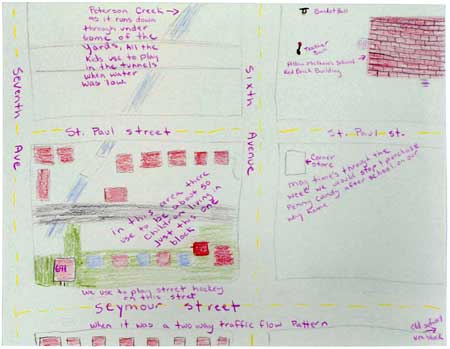

Introduction

01 The central objective of the Tranquille project is to explore the lived experience of place. We share with many others an interest in meaning, but a notion of meaning that is not restricted to narrowly linguistic or cognitive senses (see, for example, Shalin). In this regard, it would be accurate to say that we want to explore the interface of meaning and experience, and to show how meaning is grounded in human physicality and emotionality. The philosophical inspiration for the research is the phenomenological tradition, though we rely more on Merleau-Ponty than Heidegger. It is widely recognized that Merleau-Ponty owed an "enormous debt" to Heidegger (Carman and Hansen 10). They shared a common interest in the links between self and world and both sought "to reverse the ontological priorities of Cartesian rationalism" (Ingold 169). But in contrast to Heidegger, Merleau-Ponty explored in considerable detail the crucial role of human embodiment and its relation to "being in the world." Merleau-Ponty's view of the importance of embodiment is expressed in the quotation cited above, where he speaks of knowing the world through the body, and there is a sense in which our analysis starts from this idea of embodied knowledge. We see it as a key element of place-making and of the processes through which places become remarkable (as Gieryn puts it) to those who inhabit them.

02 However, we should stress that the influence of Merleau-Ponty is not limited to a general theoretical perspective. His ideas also point toward storymapping, the basic methodological tool of our inquiry. Consider the following passage: "The lived is certainly lived by me, nor am I ignorant of the feelings I repress, and in this sense there is no unconscious. But I can experience more things than I can represent to myself, and my being is not reducible to what expressly appears to me concerning myself" (345-346). The claim that "we experience more than we represent to ourselves" offers a useful perspective on the storymapping method employed in our research. Storymapping helps make experience visible and intelligible without stripping away the sensuality that gives our experiences their defining features. Storymapping thus serves as a valuable tool for exploring the experience of place, for "imaging place" in a way that does justice to Merleau-Ponty's views on the importance of human embodiment and perception.

03 Before providing a more detailed account of our research, we note that the forms of embodied knowledge discussed by Merleau-Ponty have both practical and aesthetic value. They enable and inform new ways of appreciating the sensual properties of the world. For the naturalists, who were one of the many groups in our study, the source of aesthetic pleasure is an edge place, an undeveloped area located next to a small city. While the naturalists do not reside in this place, they inhabit it, as Merleau-Ponty might say. Their capacity to appreciate its extraordinary qualities has been cultivated and refined over time. This may not be dwelling in a fully Heideggerian sense: it does not presuppose an idealized rural setting (Obrador-Pons). But it reminds us that development in its many forms entails both a loss of certain kinds of place and a loss of the sensibilities grounded in a deep knowledge of place. Understanding and honouring these sensibilities is a basic goal of this research.

The Storymapping Method

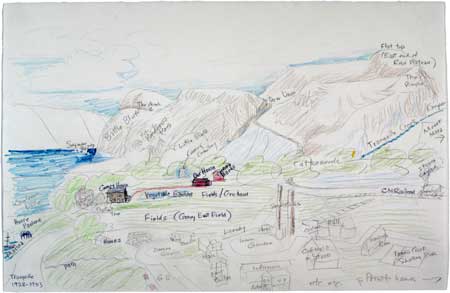

04 The storymapping method involves a gathering of personal images and verbal narratives. We first used storymapping to explore the place attachment associated with neighbourhoods. In group and semi-private settings, respondents were asked to produce a map (or image) and then to comment on that map ("walk me through your map" was a phrase we sometimes use to begin our conversations with respondents). In this research on neighbourhoods we found some evidence to support our hypothesis that "certain negative aspects of modernization—social exclusion and the homeless mind experience—[would] be felt less acutely among residents of the small city" (MacLennan et al. 146). Our efforts to understand what the respondents were saying were supported by the insights of artists who helped us appreciate the way respondents "negotiate personal space within the familiar visual forms of maps...pictures [and other] representational styles" (MacLennan et al. 148).

Storymap, from the "Neighbourhoods" project, 2004. Larger version

05 Artist researchers also figure prominently in our current research. Early on we recognized the tendency (noted by Garrett-Petts, this volume) among social scientists to assign the artist a secondary role in the research process. Working against this tendency we devote special attention to the visual—and indeed to multiple forms of representation—seeking a dialogue with artistic modes of inquiry, exhibition, and performance. Our intention is to move toward a genuine transdisciplinary bridging of artistic, social scientific and other methods of investigation.

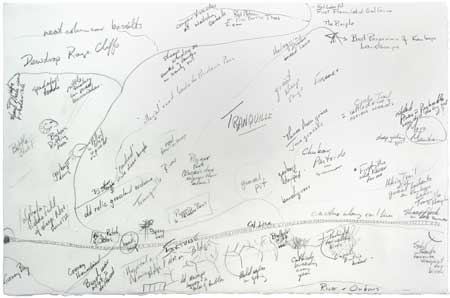

06 In our current research employing the storymapping method, we are investigating edge places. An edge place is an undeveloped area located next to a city. From the perspective of developers and some city planners, edge places are "empty" and, in their present state, devoid of meaning and value. However, for the persons and groups who make use of edge places, such a characterization is misleading, to say the least. One particular edge place captured our attention because of the diversity of groups we encountered there. Situated at the mouth of a small river (the Tranquille River) flowing into a lake, this edge place serves as a retreat for youth, naturalists, parents with children, bicyclists and many others. We decided to use the storymapping method to better understand this edge place (the Tranquille area) and the fascination it holds for a broad range of user groups.

The Tranquille area, Google Earth. In the lower right-hand portion of the image is the Kamloops Airport that marks the western boundary of the developed part of the city. The Tranquille area radiates outward from the farm that is flagged in the center of the image. Larger version

Meeting the Naturalists

07 The first major storymapping session in the edge place project was organized to correspond with the monthly meeting of the local naturalist club. One of the members of our research team is a member of the club, and we knew that many of the naturalists had an intimate knowledge of the Tranquille area. We met the naturalists as a group and presented a brief overview of our past research by showing examples of storymaps produced in the neighourhood project. The naturalists were then invited to create their own storymaps of the Tranquille area, using art supplies we provided. Afterward members of the research team moved to various corners of a large room to conduct individual interviews. One naturalist who produced a particular storymap was asked to comment on that map in an interview that lasted about thirty minutes.

A

view of the wetlands located next to the Tranquille Sanitarium.

The wetlands

are a favorite site of the naturalists and one that is featured in several of

their storymaps.

08 The data produced at a storymapping session consist of the respondents' storymaps and a transcription of the interview between the respondents and a member of our research team. Analyzing this material is a challenge and members of the research team continue to work to refine the interpretive method that is best suited to data that includes linked images and texts. To provide the reader with a sense of the complexity of the data and examples of how we analyze it, we refer below to two of our naturalist interviews. The first interview was conducted at the session described above (the naturalist monthly meeting) and the second was conducted at the Tranquille site with the naturalist member of our research team.

09 The daughter of one of the first European inhabitants of the Tranquille area, the respondent (Joan) has lived in the area for nearly eighty years. Her situation is unique in that her relation to Tranquille is not just through an appreciation of its natural characteristics. Her father worked with the first homesteaders and later was an employee of the TB Sanitarium that was built near the river. The storymap she produces is drawn with great care. It has many features of a conventional perspectival landscape but it includes some intentional anomalies. Objects that matter to Joan—a grave marker, her home, and the home of her neighbors—are colored and drawn larger than the rules of linear perspective would permit for mid-ground details.

Joan's storymap, 2008. Larger version

10 Joan uses the map/image effectively to communicate the complex mix of natural and historical features that comprise the Tranquille area and the particular objects that are important to her. The image/map conveys the look and feel of the place in a way that would be difficult in a narrative alone. In this way it illustrates our belief that map/images play an important role in capturing the sensorimotor grounding that is integral to a person's attachment to place. But what this interview suggests is that the map alone does not tell the whole story. It is through the map and interview together that we come to a deeper understanding of why Tranquille matters to Joan and how Tranquille figures in her sense of self.

11 Particularly interesting is the right side of her drawing. There it seems she is compressing a panoramic view into the perspectival landscape to indicate the importance of the Tranquille River. When the topic of the creek is addressed in the interview, the respondent's attention moves us away from the carefully rendered landscape. The shift in focus is signaled by her comment, "I should have drawn the creek all through the trees..."—and in the account that follows she offers a fresh perspective on how this place serves as a source of meaning and value to her. Instead of portraying the environment as a scene of beauty or as an object-filled map, her interview portrays the environment as a setting for action, a place where an embodied being can exercise and extend her sensorimotor capacities. "We grew up pretty wild...we knew the canyon intimately...we knew where the springs were and all the little creeks...." Distances in this landscape (not portrayed in her storymap) are measured by the body's movement and physical exertion. She uses the phrase "a hard day's hike" to describe the extent of the area she explored with her siblings. But the phrase also conveys a sense of pride and accomplishment: the environment as a place where a young person's agency is tested and displayed.

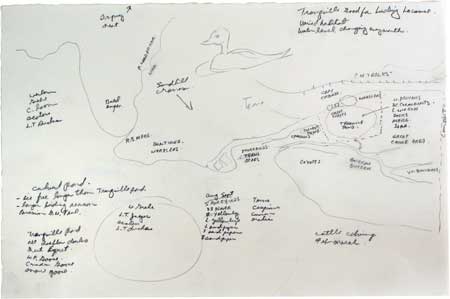

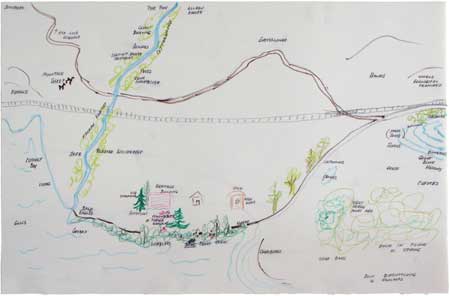

Tom's Storymap, 2007. Larger version

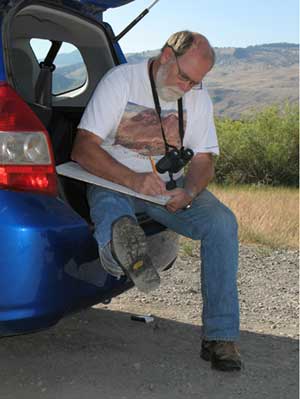

12 The second map, created by Tom, an ecologist and faculty member in biological sciences at Thompson Rivers University, is different in kind from both Joan's map and other maps that have been created as part of earlier story mapping projects. In part, this is because his map was produced on site, Tom sketching it out while sitting on the rear bumper of his Subaru in the parking lot where bird watchers gather. It is otherwise different for the intensity of detail that the map conveys: an ecologist's knowledge of the landscape together with the manner in which that knowledge is represented on the map. What Tom creates is a map that relies primarily on textual references to the landscape's ecological features, but with a strong pictorial sensibility achieved through the relational placement of the textual features. With the relational arrangement more important than any attempt at a unified scale, Tom has managed to situate a broad and complex landscape onto the rectangular format of his 11" x 17" sheet of drawing paper. A few key cultural features—gravel roads as well as the C.N. rail lines and tunnel—are drawn on the map in a conventional manner as a means of providing some basic points of reference (and hence also as a suggestion of scale in the most general sense for those already familiar with the Tranquille area).

13 Details of Tom's map reveal such personal interests as the location of the sighting of his "First Blue Wild Racer" (a kind of snake), marked with an asterisk, and the "Bighorn Rutting Area," one of the few details that is embellished with a doodle-like drawing. Slightly off the lower right-hand edge of Tom's map is another point of interest: a large boulder, a glacial erratic, that had been carried by the ice to a flat area that is high up on the flood plain and now adjacent to Tranquille Road. Between the road and the boulder is a cattle fence, and between that and the boulder are a few smaller rock fragments of varying sizes. What interests Tom in this boulder is how it is representative of the geological history of the area (volcanic origin) as well as the evidence that it presents of glaciation (more than 10,000 years ago) at the same time as it records a record of the more recent—and cultural—history of ranching in the Tranquille area. The smaller fragments, he tells us, result in part from annual cycles of freezing and thawing but also from the boulder having a hundred-and-fifty-or-so year history of cattle rubbing up against it and breaking pieces away.

14 Through their respective drawings, Joan and Tom suggest two quite different manners of conveying an embodied sense of place through personal mapping. Joan's map (and those of others) generally follows the expectations of landscape drawing and painting that have become naturalized within western culture, yet allow for moments of digression from those conventions where there is something of personal value to note. The producers of other maps are less inclined to represent their knowledge and stories in visual terms and are instead compelled to allow a written form take precedence. Often, though, as Tom's map shows, there is some overall composition arrangement to a map that might appear at the outset to be only text. Building upon observations from the earlier "Neighbourhoods" project, our analysis of the naturalists' maps leads us to think of there being a continuum from the image-based to the text-based maps, with many permutations and digressions along the way.

Willie's Storymap, 2008. Larger version

Eleanor's Storymap, 2008. Larger version

15 We should add that as we analyzed the maps it became apparent that the storymaps project will be extended in a significant way if we, first, engage some of the participants in follow-up mapping sessions and, second, increase the number of mapping sessions that are undertaken onsite. Tom's map, created in the parking lot where the bird watchers gather, and in full view of much of the surrounding topography, was created in such a manner and provided a ready point of departure for Tom to take us into his landscape. The initial maps, together with interview transcripts, suggest many locations that are of particular interest to the naturalists and that would benefit from on-site visits and mapping. Going to these places with the naturalists during multiple sessions will encourage them to show us not only the points of interest easily located on their maps but also some of the places that are typically noted as being beyond the edges of the maps that they have drawn, effectively taking us off the edges of their existing maps. It will also allow us to pursue our interest in multiple forms of representation and to determine whether the map makers adopt a different style when producing maps onsite.

Tom, on site, drawing his storymap.

Tom on the benchlands overlooking the former sanitarium and the wetlands beyond.

16 The storymaps and accompanying interviews represent highly personal accounts of the environment. Joan speaks with pride of a young person's early experiences of independence and Tom remarks somewhere on how his work and his passions overlap in a fondness for the Tranquille area. For both respondents, the storymapping process appears to enhance their self-understanding, their sense of who they are and what they care about. But the storymaps and interviews are more than personal artifacts. As cities expand into surrounding environments, politicians make public commitments to environmental and heritage values and record those commitments in municipal plans. However, such commitments tend to be overshadowed by the worldviews of developers. What the storymaps/interviews address is precisely what is lacking in official land use plans: the emotionality and appreciation of place that only a more personal account can express.

Discussion

17 Over twenty-five years ago Gregory Ulmer offered a powerful statement observing a "break with 'mimesis,' with the values and assumptions of 'realism'" (83). In "The Object of Post-Criticism" he announced a new program for the critique of culture and art. There is a sense in which this anti-realist position is reflected in our interest in multiple modes of representation. Embodied knowledge influences in a fundamental way our relation to the world. However, our interest is in how this knowledge both informs and is informed by other ways of representing the world we inhabit. With this in mind, we have developed a proposed research outcome that invites local inquiry as a form of public performance: a series of walking tours that afford ongoing access to key places in the Tranquille area. The walks will be supported by various modes of representation, including digitized accounts (podcasts produced by local user groups) as well as conventional brochures and fold-out maps. The idea is for participants to appreciate how the "realities" of place are shaped by multiple forms of representation and how the embodied knowledge Merleau-Ponty considered "original" interacts with, builds on, and in some cases challenges knowledge that exists in other forms.

18 In conclusion, we should note that our plans for the walks were inspired in part by a recognition that the naturalists' sense of place is a unique and perhaps even endangered sensibility. We have therefore entered into a partnership with an elementary school in the local district and anticipate that the children will participate in field trips to the Tranquille area, where they will have an opportunity to interact with the naturalists. Drawing on these experiences, the children will produce text/image projects (including their own walking tour podcasts) to display their developing knowledge of the natural and cultural history of the Tranquille area. In this way the students will have a chance to experience edge places directly and to interact with those who are passionate about them. This, we hope, will enhance the students' engagement in the learning process and help them appreciate the value of open spaces. But we also expect that it will enable students to enter into the complex relations between embodied knowledge and various symbolic representations of place.

Acknowledgements

Our research is supported by a grant from the Small Cities Community-University Research Alliance, funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. We want to acknowledge the research contributions of those student research assistants working with us on this project: Justin Philcox, Ashlynn Harris, and Johanne Provençal.

Works Cited

Carman, Taylor and Mark Hansen. "Introduction." In The Cambridge Companion to Merleau-Ponty. Ed. Talor Carman and Mark Hansen. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2005. 1-25.

Gieryn, T. "A Space for Place in Sociology." Annual Review of Sociology 26 (2000): 463-496.

Heidegger, Martin. "Building, Dwelling, Thinking." In Martin Heidegger: Basic Writings. Ed. David Farrell Krell. San Fransciso: Harper, 1992. 343-363.

Ingold, T. The Perception of the Environment: Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge, 2002.

MacLennan, D., D. Lawrence, W.F. Garrett-Petts and B. Yourk. "Vernacular Landscapes: Sense of Self and Place in the Small City." In The Small Cities Book: On the Cultural Future of Small Cities. Ed. W.F. Garrett-Petts. Vancouver: New Star, 2005. 145-162.

Merleau-Ponty, M. The Phenomenology of Perception. Trans. C. Smith. London: Routledge, 2003.

Obrador-Pons, Pau. "Dwelling." In Companion Encyclopedia of Geography Volume 2. Ed.,Ian Douglas, Richard Hugget and Chris Perkins. London: Routledge, 2007. 953-964.

Shalin, Dimitri. "Signing in the Flesh: Notes on Pragmatist Hermeneutics." Sociological Theory (September 2007): 193-224.

Ulmer, Gregory L. "The Object of Post-Criticism." In The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture. Ed. Hal Foster. Port Townsend, Washington: Bay Press, 1983. 83-110.