Writing the Ruins: Rhetorics of Crisis and Uplift after the Flood

Doreen Piano

[1] In mid-November 2005, I returned to New Orleans, where I had moved weeks before Hurricane Katrina. On that overcast day, driving into the city on I-10 West, I passed by neighborhoods and commercial districts scarred by the dual hurricanes—Katrina and Rita. Blue tarps covered endless rooftops, glass facades of corporate buildings blistered and peeled as if in the sun too long, and highway billboard signs toppled on their sides. Off the highway, closer to my neighborhood in Mid-City, I drove down Canal Boulevard, seeing for the first time what would become a naturalized sight, houses with their insides exposed, doors flung open or ripped off, windows busted in, and wires dangling from half-fallen trees. All over the street, glass was everywhere. Debris lined the curb where homeowners had begun the difficult work of gutting their homes, stripping the interior, and in some cases, the exterior so that you could often look through an empty doorframe or picture window and see the backyard beyond. These sidewalk pyramids appeared as clumped mounds of nothing, although at one point they were something—they were someone's. Refrigerators huddled together on street corners, duct tape hugging their girth; some had messages written on them with phone numbers for gutting services, others claimed, "Open At Your Own Risk" or "Free Gumbo Inside."

[2] Later that day, I found myself compelled to roam up and down deserted sludge-encrusted streets of Lake Vista, Lake View, and Gentilly. Even with the car windows closed, dust hit the back of my throat. Intersections were free-for-alls, with traffic lights on the blink, not that it mattered because there were hardly any vehicles around other than those destroyed by the flood waters. Occasionally you'd see utility repair trucks or workers hired by the Corps of Engineers to clean the streets block by block, attempting to rid the city of some of its debris. Their bright orange vests underscored the eerie stillness of being in a city devoid of people, many areas still without power. Two months after the flood, you could drive from Metairie to Mid-City or from Mid-City to Uptown at night and be ensconced in complete darkness for a good part of the trip. As if you were in the middle of the countryside—away from it all.

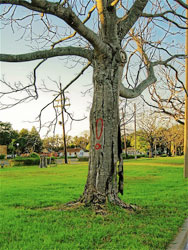

[3] After a while you just get used to it, seeing neighborhoods like this. At least that's what we say to each other, but truly I don't think we ever do. Neighborhoods are no longer referred to by name but by how high the water rose. Lakeview got eight to eleven feet, Mid-City from three to six, Broadmoor a little bit more; in the Lower Nine, most parts of Gentilly, and Chalmette, water didn't leave a line, it topped the roofs. Imprinted on every house—even fences, bushes, street signs, and cars bear it—the waterline became what Chris Rose of the Times-Picayune aptly described as "the city's bathtub ring," the sludge brown residue that stains cars, houses, trees, bushes, fences, and walls, bonds all of our flooded neighborhoods, an aspect of the city that is mindless for once of ethnic, class, and racial divisions. The parts of town that received no water, termed "the sliver by the river" and the "aisle of denial," we resent, even though we know that these areas keep the city alive.

[4] Besides the waterline, the other ubiquitous flood marker, the tattoos on houses and rooftops that first responders left, conveys a surprising amount of information: first and foremost, the number of people found dead or rescued and the date of entry, but also what group entered the structure (NYPD, NE, CA5, PA3), whether or not animals had been rescued (SPCA, HSUS) or found dead (2 dogs DOA), and if some needed to be fed (F/W). As the waterline has faded, these Xs remain, becoming critical reminders of the immense relief effort of volunteers and their adept use of low tech methods of communication. These first responders in some way set the stage for other forms of public writing to emerge since the flood, although who can forget the poignant images of abandoned citizens on top of buildings or stranded on highway overpasses spray-painting messages such as "Help Us" and "We Need Food" that attested to how victims of the government's neglect made use of writing to commandeer their own rescue and address their desperate conditions. Those images remain vivid to me because the use of writing in its most material and tangible sense manifested a narrative of inner-city urban life, one that had always been there but that had been neglected because the spaces themselves (of poverty, crime, despair) were invisible. Until Katrina, these rhetorics of crisis could not be articulated in such a way as to be heard (and seen). However, the use of graffiti—itself a synecdoche for crime, poverty, violence, disenfranchisement—by New Orleans' urban poor deployed a rhetoric of crisis that many had already been living long before the levees broke. Those images of writing are a grim yet hopeful reminder of the power of visual rhetoric to draw attention to the material conditions in which we live and, in the case of New Orleans' stranded citizens, to survive.

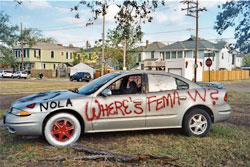

[5] Since the flood, New Orleanians continue to generate public discourses about the conditions of the city, its political climate, its inability to return to the past nor to figure out a future. Spontaneous memorials, spraypainted messages, and found object tableau have contributed to a narrative of New Orleans life post-Katrina that cannot be contained in books, photographs, or even oral testimonials; these demonstrative acts involve re-writing Katrina through display and performance, qualities of New Orleans' life that have always played a major role in the city's culture, but that belie the Big Easy moniker New Orleans carried pre-Katrina. [1] Abandoned cars, curbside refrigerators, sides of houses and businesses, doors and sidewalks, even trees have all become canvases for people to express joy and love, sadness, solidarity, anger, violence, hostility. While graffiti writers often identify themselves through their tags, this writing is less about style and more about communicating direct messages to various bureaucracies (FEMA, the Bush Administration), public officials (Nagin, Blanco, Bush, Brown), looters, and fellow residents, while often paying homage to New Orleans itself. My first sightings of this post-Katrina graffiti occurred on the day of my return as I passed Terranova's, my local Italian grocery store, and saw painted on their shuttered windows: "St Joseph, Pray for Us." [2] Later that day, on the whitewashed wall of a cemetery, I noticed the word Love was scribbled in red and green paint alongside several G clefts.

[6] As a photographer of these sites, I see these public demonstrations of affect as both rhetorics of crisis and of uplift. [3] Interestingly, the willingness of people to write on their own houses and cars, to recast property as rhetorical in terms of utilizing both the time and actual place of crisis as a vehicle (no pun intended) of expression conveys a movement from object (of pity, of government handouts, of city planning) to subject. At least symbolically, these displays of rage, humor, and retribution represent an attempt to regain a more active role in the recovery process by engaging in a dialogue with neighbors, residents, and passers-by while simultaneously exhibiting the frustrations, hopes, fears, and anxieties that have become the constant emotional states of people living in the ruins. At the same time that these public displays narrate residents' despair and anger, their use of familiar urban spaces and objects memorialize the passing of people, the destruction of places and things—a loved one's picture posted on the front of a house, ruined cars converted to flood memorials, and a once water-drenched teddy bear hanging in a tree.

[7] What compels me to photograph these affective sites is perhaps my own desire to witness some return of life in areas of the city that appear moribund: "dead neighborhoods" as opposed to "those that are coming back." I want to document the struggle that ordinary citizens undergo as they attempt to recover or recreate their former lives, honor the loss of life, and assign affect to place. Additionally, these images illuminate how material culture and low tech methods of communication commemorate and comment upon life in New Orleans post-Katrina. The commentary is often acerbic, laced with humor, riddled with racism (Ray, Shove a Hershey up your Ass), sexism (Katrina, You Bitch), and classism (I'm Home, Gun). These images exhibit moments of recovery, loss, and rebirth indelibly linked to place and time, always alluding back to "the event," a distinct pre- and post-Katrina timeframe that defines our lives. Placed within a chronological time frame, one can read these public displays as continually redrawing and complicating but also re-enacting the same socially complex landscape before Katrina, one whose barriers of race and class have not diminished but whose boundaries are more dramatically and incessantly displayed. These affective inscriptions also memorialize the flood and its painful aftermath differently than the more conventional spaces of civic-funded memorials by exposing the violence of feelings that erupted when people were left to save and protect themselves, the anger and humor of a returning citizenship coming to terms with what has been lost, what doesn't work and who is responsible. Additionally, they illustrate the vigilance with which people have undertaken not only to rebuild their lives but to protect their property, their neighborhoods, and to honor their city. They act as counterarguments to the more powerful discourses circulating nationally that doom the city's future.

[8] In so doing, these messages of affect reinsert humanity into urban spaces that have been abandoned not just by homeowners but by government on all levels. Many parts of the city are languishing, caught in a liminal state of growth and decay. A year later weeds rather than water overpower houses, bands of foraging raccoons take shelter on desolate porches, and wood frame houses list to their sides as if adrift in an unruly sea. As New Orleans continues to fade from the public sphere, especially after the passing of the first anniversary, perhaps, what Andreas Huyssen defines as "memory practices" [4], the compulsion by many Western cultures to formulate new ways of responding to the ways in which contemporary lived experiences, particularly traumatic and catastrophic events, are intensely captured and quickly forgotten by visual and print media, will be what ordinary people do to keep their opinions, their histories, and their memories alive.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Robin Goldblum, Hamilton Carroll, Darrel Mayers, and Craig Saper for their comments and feedback on a version of this essay and the accompanying images.

Notes

[1] While the photographs I have taken reveal the unique ways in which New Orleanians use found objects and writing to express their relation to the city, there has also emerged a cottage industry of Katrina souvenirs, iconography, and memorabilia produced by local businesses that include T-shirts, tattoos, banners, fleurs-de-lis, stationery, jewelry, and bumper stickers. These items not only are seen as collectibles but arm citizens with a 'survivor' status that is infused with an intense regionalism such as my neighbor's bumper sticker one finds on many cars throughout the city that reads New Orleans: Proud to Swim Home.

[2] St. Joseph is an important religious figure to the Sicilian community of New Orleans and is honored on March 19th with the construction of altars around the city. For more information on the commemorative ceremonies associated with this patron saint, see Anna Maria Chupa's "St Joseph's Day Altars" essay available at «http://www.houstonculture.org/cr/stjo.html»

[3] In future work, I will investigate more deeply the relationship between public display and emotional life as found in the writing, ad hoc memorials, and tableau I've been photographing. Additionally, I intend to place them within the context of more conventional sites of remembrance as found in current museum exhibits of Katrina ephemera, state and city-sanctioned memorials, and one-year commemoration ceremonies. Scholarly interest in "public sentiments," known as the Public Feelings Project, has been spearheaded by queer/feminist scholars such as Lauren Berlant, Ann Cvetkovich, Lisa Duggan, and Ann Pelligrini among others. See Scholars and Feminists Online, Special Issue: Public Sentiments available at «http://www.barnard.columbia.edu/sfonline/ps/contribu.htm»

[4] Huyssen, Andrea. "Present Pasts: Media, Politics, Amnesia." Globalization. Ed. Arjun Appadurai. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001.